Cameronian Commandos

#WW2at75

This is the first of four posts that will explore stories of Cameronians who served beyond the Regiment in the Second World War, in what we might term today as ‘Special Forces’ roles. The purpose of these posts is not to elevate the contribution these men made above others in the Regiment, but to demonstrate the variety of remarkable ways Cameronians served in the War. As with all of our blog posts, the men featured tend to be those whose stories are tied to certain objects, photographs, or archival material held in the Museum collection. If you have information on Cameronians who served in these types of roles, please do tell us in the comment section below.

This post will look at Cameronians who served in the Commandos and/or the Special Air Service (SAS), with subsequent posts exploring Cameronians who went on to serve in the Parachute Regiment, the Chindits, and the various specialist roles played by the 6th and 7th Battalions as part of the 52nd Mountain Division.

Hundreds of soldiers of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) saw service beyond the Regiment in a variety of roles during the Second World War. After the fall of France and the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, a number of junior officers opted to transfer to the Royal Air Force. With the BEF back on British shores, and the Army placed on a defensive footing, service with the RAF appeared for some to offer the best prospects of seeing action with the enemy, especially as the Battle of Britain was being fought in the skies overhead in the summer of 1940.

One of these young officers was John Lang Steele, from Lanark. A pre-war Trooper with the Lanarkshire Yeomanry he was selected for officer training and, on being commissioned, was posted to The Cameronians Infantry Training Centre at Hamilton in early 1940. Subsequently posted to the 12th Battalion at Lossiemouth, John transferred to the Royal Air Force. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for gallantry as a bomber pilot in the Middle East in 1943. John was killed on operations in December 1944, with the rank of Squadron Leader. https://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2237860/steele,-john-lang/

Beyond the RAF, there were soon to be other ways in which those eager to take the fight to the enemy could find satisfaction.[i] A new strike-force called the Commandos was being raised with the purpose of carrying out daring hit-and-run raids along the coastline of occupied Europe. From the Commandos would grow other elite fighting units now famous around the world, such as the Special Air Service (SAS), and the Parachute Regiment. Cameronian soldiers would see active service in all of these ‘special forces’ units in the Second World War. These are just a few of their stories.

Captain Jack McNeil

Jack McNeil was a Territorial Army officer who had been commissioned in May 1939, just months before the outbreak of the Second World War. It was while serving with 7th Cameronians that Jack volunteered for service in the ‘Independent Companies’ being raised for service in Norway. With the BEF occupied in France and Belgium, the Independent Companies (formed from Territorial Army divisions based in the UK) were to be sent to Norway to resist the German invasion. Jack would see active service in Norway and was wounded in action. With the aid of the Finnish Red Cross he was able to make his way back to Britain, arriving home just as the BEF were being evacuated from Dunkirk. He joined the 2nd Special Service Battalion in November 1940, and ultimately No. 9 Commando.

Jack would see extensive combat service with No. 9 Commando in Italy. In late December 1943, he commanded ‘Y’ Force, one of three sub-groups of No. 9 Commando during the action to assist X Corps’ crossing of the River Garigliano:

Once ashore, ‘X’ Force began to establish the bridgehead, and had soon cleared the mouth of the river, killing all the Germans found there except one; ‘Y’ Force moved off to Monte Arengto, and ‘Z’ Force, after sending out a patrol, set out for the amphitheatre. ‘Y’ Force, one hundred and twenty strong, under Captain J. McNeil, had now eight hundred yards further to go than had been planned. Speed was therefore essential. They pressed on over broken mine-strewn ground, and at 03.20 hours began their assault. The enemy were soon dealt with. A tank discovered in a cave was destroyed, its crew killed, and the position was captured for the loss of two officers and two men wounded. In his withdrawal McNeil followed a new route to avoid the mine-fields, and this took him and his men close to Force ‘Z’ which, under Captain R. Cameron, was moving to the assault of the amphitheatre.

‘The Pibroch of the Donald Dubh,’ to the sound of which Cameron was wont to charge, came to the ears of ‘Y’ Force, and to avoid the danger that the two forces might in the darkness mistake each other for Germans, McNeil ordered his piper to play ‘The Green Hills of Tyrol.’ [ii]

Jack McNeil was later appointed as an instructor and advisor to the Free French forces that were to be employed in the attack on the island of St Elba.

Jack ultimately served as Commandant of Carronbridge Prisoner of War camp, near Thornhill in Dumfries and Galloway. Here he would encounter Adolf Kuechel, a German prisoner of war. Jack provided Kuechel with the materials to allow him to pursue his passion for painting. In return, Kuechel painted the fine portrait of Captain McNeil – reproduced above.

Captain Martin Ferrey

Martin Ferrey enlisted in the ranks of the Scots Guards in June 1940. During his recruits’ training he was identified as a Potential Officer and sent to RMC Sandhurst. Commissioned in February 1941, Martin was posted to The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) Infantry Training Centre at Hamilton.

© The Ferrey family, reproduced with permission.

In an unpublished account of his military service (held in the museum collection) Martin recalls that he requested The Cameronians mainly on the fact the Regimental Depot (Hamilton Barracks) was close to Burnside, where he and his wife had lived since they were married in 1938. While at the Depot in Hamilton Martin was appointed Passive Air Defence (PAD) Officer, giving him the opportunity to witness first-hand the Clydebank Blitz of 13th and 14th March 1941. It was while serving as PAD that Martin heard the call for volunteers for the Commandos:

“A special force of mobile and highly trained troops is being created…they will operate by means of raids behind enemy lines or where shock troops are required…they will be demolition and sabotage experts…must be superlatively fit…rugged, athletic…capable of feats of exceptional endurance…in view of the hazardous nature of their duties and the fact that the casualty rate is expected to be high, these troops, to be called Commandos will be recruited on a voluntary basis…”[iii]

Martin half-jokingly admits that he volunteered for the Commandos to escape the hardship of life at Hamilton Barracks – namely having to learn and take part in Highland Dancing on Mess nights. Commando life would be “baby stuff compared with Scottish dancing.”

Martin completed the grueling Commando training courses at Glenfeshie and Lochailort in Scotland, and on-the-job training with No. 9 Commando at Kirkudbright and on the Isle of Arran. It was at Lochailort that he was issued with the infamous Fairbairn Sykes Fighting Knife, a weapon synonymous with the Commandos and which, to this day, still forms part of Special Forces unit insignia the world over.

Martin fought with No. 9 Commando on multiple operations in Italy, culminating in the Commando attack on Mount Ornito in February 1944, as part of the Anzio landings. This was to be Martin’s ‘last show’ with No. 9 Commando:

“We had reached the summit of Ornito, and simultaneously an intense barrage of German 88 millimetre shells from the direction of Mount Faito laid down a steel curtain of high explosive: the enemy had our range precisely and salvo after salvo was a bull’s eye; 9 Commando was the eye of that bull, and being on solid rock increased the killing circle of each shell… I seem to remember an exceptionally ear-splitting whistle of a descending shell and a rock-pulversing explosion which picked me up bodily and threw me through the air across the summit of the mountain. The pain was severe and I think I may have lost consciousness for short periods.”

Martin was given a shot of morphine by the Medical Officer and was in the process of being stretchered off the mountain by his batman, Jack Anderson[iv] and a Corporal McAuley, when the group were again hit by shellfire:

“I do not know what happened next but I must have been hit again, this time in the left arm and jaw below my left ear and I seemed to be in a patch of scrub and low bushes. Somebody beside me was screaming as he burned with phosphorous bombs which must have ignited in his pockets or equipment, and I first I thought he was American from the shape of his steel helmet, but I think I must have been mistaken and that he was almost certainly a German and I have always regretted I was too confused to put him out of his agony with a round from my pistol, for nobody could have possible survived that incineration.”

Despite his multiple wounds, Martin was able to make his way down the mountain and reach the assembly area. There he received further emergency treatment before being evacuated on a stretcher-laden donkey. Martin’s account somewhat makes light of the considerable time he had to spend recuperating in hospital, and indeed his playful character and sense of humour often masks the grim reality he faced during his time in service.

A series of letters written to his family in England, however, reveal that Martin’s wounds weren’t limited to the physical. Writing from the psychiatric ward of the military hospital, Martin relates:

“I have seen the tragedy of shattered bodies on the battlefield, I have seen them coming in to hospital like red meat and rags on a stretcher, but a week here has convinced me that the tragedy of the shattered mind is more horrible. It was called shell-shock in the last war and is now termed ‘Anxiety-neurosis’ but call it what you will it exists.”[v]

Martin’s wounds had resulted in an unusual disfigurement, whereby his head was permanently tilted at an angle to one side. No amount of physical examination or treatment of the afflicted areas could find cause or yield a remedy. Doctor Palmer[vi], the chief psychiatrist, was convinced the cause was mental rather than physical. In a letter to his sister, Martin recalls the treatment employed by Doctor Palmer:

“I was under sleep treatment for 2 ½ days and [he] gave me a day to recover from the drug which left me quietly and magnificently tight, and although my head still hung, my temper which had frayed alarmingly because of my wretched condition, had smoothed, and I felt positively benevolent. Palmer sent for me and explained that he was going to use ether to loosen my tongue, and he also asked me if I minded an audience as he wished to demonstrate his technique. I had no objection but was surprised when three sweet young things from the Hospital Massage Dept. filed in, also three burly R.A.M.C. male nurses. I lay on a couch, the mask was applied, followed quickly by the smell of ether, and then Palmer began to recount the events of that shocking night [the attack on Mount Ornito]. His voice was far away but clear, and I found myself taking up the story. It was the strangest sensation and difficult to describe, but I felt like three distinct personalities. Martin (A), who knew he was lying on a couch in a room talking, Martin (B) a detached entity watching and describing what Martin (C) was doing. (A) remained static, (B) had to shift about the battleground to keep in touch with (C)! The process was interrupted for a spell by Martin (A) who was a bit naughty and started to fight and struggle, but he couldn’t help it and had a terrific fracas with the R.A.M.C. His knee smashed into something soft, his finger thrust up someone’s nostrils and nipped hard, just as he had been taught to defend himself. Martin (B) was also naughty as he used some filthy soldiers’ language. However we all calmed down eventually as ether was liberally sprinkled on us. The scene came back with hideous clarity, the moon filtering through the clouds, shells screaming through the air, the orange and red stabs of flame as they burst amongst us, earsplitting detonations, clouds of black and yellow smoke and even the stench of Lyddite, and Palmer’s voice distant yet compelling, mercilessly dragged it all out. It is impossible to say what was asked and answered as I remember nothing after the second dose of gas except that I talked and talked rather like a gramophone gone haywire. The climax came when I was recovering full consciousness. The voice was saying “You want to cry – you are going to cry.” Recollecting my audience I fought hard for about 30 seconds, gritted my teeth and said “I’m damned if I do” – and promptly burst into floods of tears! Never had I felt so silly, sitting on a couch weeping as though my heart would break, with three women looking on. It is all apparently part of the treatment, and I am told I have been wanting to cry ever since I was wounded and nothing could benefit me more than to uncork this bottled up emotion. My head was straight when I had time and sanity to notice it and when it started to loll again I received a hard smack on the right side of my face to remind me not to do it! The condition had been caused by the coincidence of all my wounds being on one side of my body: two bullets gashing the left arm, the shrapnel from left to right across my backside and finally the hole in my jaw below the left ear. Most of the shelling was to my left and two of my men whom I helped to die were on the left of my position. They were both very messy and one was noisy. Result – the mind said to the body “Turn away from all this noise, pain and horror.” My head turned as ordered and just stayed there. Palmer explained it thus and told me that as soon as I was properly under the ether I straightened up under his direction.”[vii]

When fully recovered, Martin re-joined No. 9 Commando. He was soon promoted to Captain and joined the Headquarters Staff of No. 2 Special Service Brigade. In his role as Staff Supply Officer, known as ‘Q’, Martin would see further service with the Commando Brigade in Yugoslavia and Albania. Martin ended his military service while on the staff of the Holding Operational Commando (HOC) at Achnacarry, Scotland.

Martin kept in touch with comrades from his Commando days through the Commando Veteran’s Association Newsletter. In a letter to Mr Henry Brown, Secretary of the Commando Association, in December 1979, Martin gave the following apology:

“Sorry I have not attended your unions since the laying up of the Commando Flag in Westminster Abbey, but as I meet former comrades and see them growing old, bald and fat it is always born upon me I am exactly the same and I find the reunions depressing rather than exhilarating!”

Sergeant Ernest Johnstone

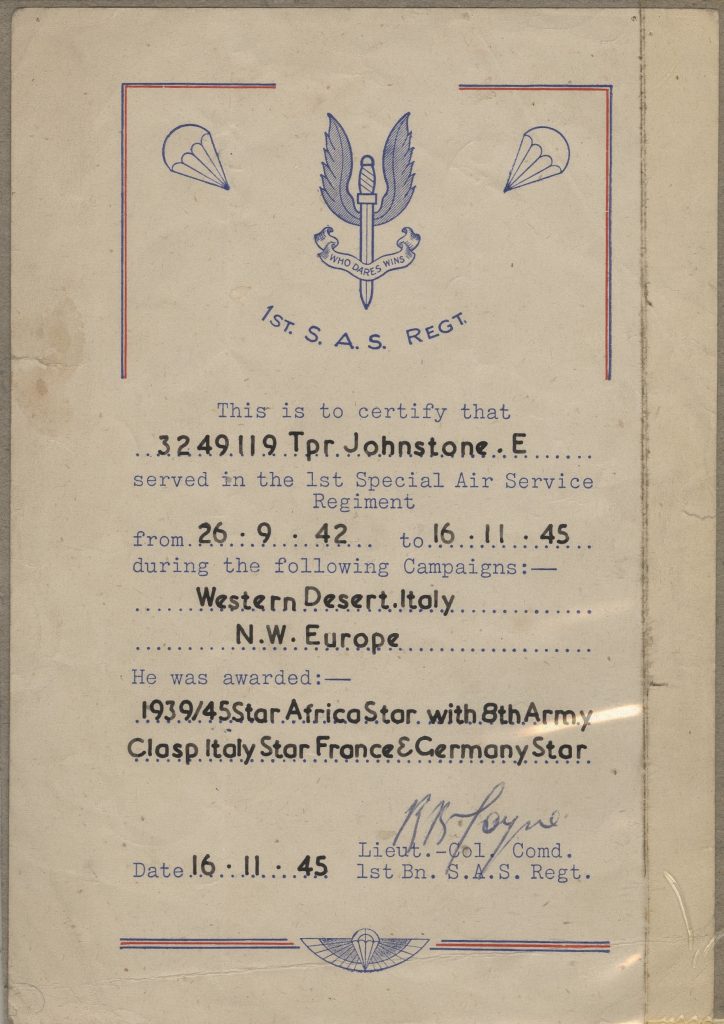

Ernest Johnstone is something of an enigma. Archival material in the museum collection tells us that he joined the Cameronians in 1940 and was finally discharged in 1963. A document from the Ministry of Defence provides a summary of his overseas service and shows wartime service in North Africa, Cyprus, Iraq, Persia, North West Europe, and Norway! Some of these places do not tally with field-service battalions of The Cameronians. A certificate of service for Ernest, helps shed some light on this. Between September 1942 and November 1945, Ernest Johnstone was attached to the Special Air Service (SAS).

It appears as though Ernest served with No. 11 (Scottish) Commando before joining the SAS. No. 11 was one of the Commando units sent to North Africa as part of ‘Layforce’, and it was as part of this formation that Ernest possibly saw service in Cyprus. This rather blurry photograph is most intriguing – it appears to show a number of Commandos on the deck of a British submarine.

A note on the reverse suggests that these men are part of No. 11 Commandos raid on Rommel’s North African HQ, code-named Operation Flipper. A mention of Ernest in The Covenanter towards the end of his service refers to him as one of the ‘Cockleshell Heroes’ – this might suggest that Ernest was involved in the canoe squadron of No. 11 Commando that would later become the Special Boat Squadron (SBS).

Even with a list of his overseas postings, it is difficult to say with any certainty which SAS operations Ernest might have taken part in, but it is likely he joined the original L Detachment, raised by David Stirling, which would later become the 1st SAS Regiment.

Ernest’s service in North West Europe coincides with a number of behind-enemy-lines missions conducted by 1st SAS, including Operations Haggard, Kipling, and Howard. Service in Norway in the immediate aftermath of Germany’s surrender in May 1945, suggests Ernest took part in Operation Doomsday; the SAS-led expedition to Norway to dis-arm German forces there and prevent the establishment of a ‘second-front’ behind which German troops loyal to Hitler could continue to oppose the Allies.

In the absence of detailed documentary evidence, Sergeant Johnstone’s wartime exploits with the SAS may never be fully known although one can only imagine he would have had no shortage of thrilling wartime stories to tell.

[i] 2nd Cameronians, who took part in the Battle of France, would once again be employed overseas from 1942, in India, Madagascar, the Middle East, Italy and North West Europe. 1st Cameronians would see continuing action against the Japanese in the Far East. 6th, 7th and 9th Cameronians would spend much of the war in a home defence role, and intensive training in preparation for the invasion of Normandy and the Liberation of Europe in the summer of 1944 and beyond.

[ii] The Green Beret: The Story of the Commandos 1940-1945. Saunders, Hilary St. George, New English Library, 1978, pp220-221.

[iii] Soldier of Misfortune, unpublished TS, Ferrey, Martin. CAM.G140

[iv] Martin would learn while recuperating in hospital that Jack Anderson was reported missing and presumed killed during the action at Mount Ornito, possibly killed by the shell-fire that knocked Martin off-his stretcher.

[v] Martin Ferrey letter, 19th March 1944, extract kindly reproduced with permission of the Ferrey family

[vi] Doctor Harold Anstruther Palmer, pioneer of the ether abreaction process of severe battle stress and head of No 7 Base Psychiatric Centre in Caserta, Italy

[vii] Martin Ferrey letter,31st March 1944, extract kindly reproduced with permission of the Ferrey family

Comments: 0

Leave a Reply