The Formation of the Regiment

We are indebted to Major Philip Grant for allowing us to share with you the following article which explores the fascinating story of the 1881 pairing of the 26th and 90th Regiments to create The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). The article was originally published as a supplement to the 2007 edition of The Covenanter, and we are very grateful to Philip for allowing us to share this recently updated version.

The Formation of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), 26th and 90th

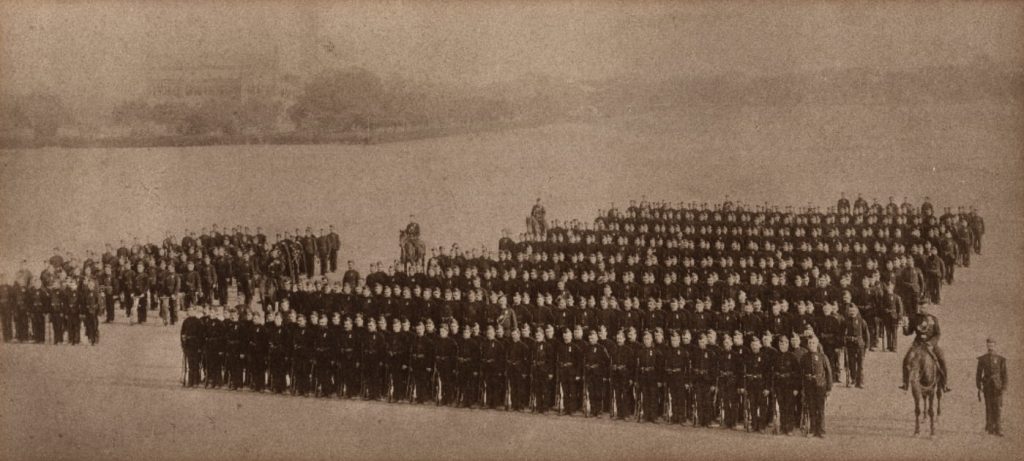

On 26 June 1882 the 26th Regiment, The Cameronians, paraded at Shorncliffe Barracks, near Folkestone in Kent[1], dressed in a new and, to them, a strange uniform. Gone were their scarlet coats with yellow facings. Gone too were their navy blue trousers and their gleaming brass buttons. In their place were government tartan trews[2] and dark green doublets with black buttons. They were parading to march off their colours for the last time. What was happening to this regiment after 213 years of service?

More than 4,000 miles away the 90th Regiment, The Perthshire Light Infantry, paraded at Cawnpore, not far from Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh, India[3]. They too were dressed in dark green doublets and the same tartan trews, and black buttons. These replaced their red coats with buff facings, and their navy blue trousers, though they had long rejoiced in the nickname the Perthshire Greybreeks[4]. They too were about to parade to march off their colours for the last time.

Thus was a new regiment born. Two quite separate entities with widely different histories – and miles apart – were brought together to form the 1st and 2nd Battalions The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). Now they wore the same uniform and the same new cap-badge. But why, how, and for what purpose was all of this taking place?

A short history of the Regiment says:

‘The original Cameronians were zealous Covenanters. Their devotion to the National Covenant (1638) and the Solemn League and Covenant (1643) meant that they would even do battle to defend their freedom to worship as they chose. Their heartland was in southwest Scotland, in Galloway, Ayrshire, and in Clydesdale in particular.

‘When their Ministers were ejected from their parishes the Covenanters followed them to the hills and worshiped at open-air services which came to be called conventicles. As the threat from government forces increased the Covenanters began to carry weapons to their conventicles and to post armed pickets to keep a lookout.’

Religious strife all but ended with the Glorious Revolution; this paved the way for the Covenanters to become part of the regular army.

‘The Regiment was formed in one day, 14 May 1689, ‘without beat of drum’. They mustered on the holm, on the banks of the Douglas Water in South Lanarkshire. Their first Commanding Officer was William Cleland whilst their Colonel was the 19-year-old Earl of Angus, son of the Marquis of Douglas. …

‘The Regiment took its name from Richard Cameron, ‘The Lion of The Covenant’. Originally a field preacher he was killed, a bounty on his head, at the battle of Airds Moss in 1680. …

‘Within weeks of their formation The Cameronians saw action as regular soldiers at the Battle of Dunkeld. There they showed their mettle with a staunch defence against a hugely superior number of rebel Highland troops, though it cost the life of the 28-year-old Cleland. From 1750 they, like all of the regiments of the line, were given a number and were thereafter known as the 26th Regiment of Foot, The Cameronians. …

‘As the 18th century drew to a close Britain faced the threat of war with the French. To counter this the government authorised the raising of a number of new regiments. Amongst them were the 90th (Perthshire Light Infantry)

‘The man who raised the 90th was a Perthshire laird, Thomas Graham of Balgowan. He was born in 1746 and in 1774 he married the Hon. Mary Cathcart. So great was her beauty, and legendary charm, that the famous and fashionable artist Thomas Gainsborough painted her portrait no fewer than four times.

‘Sadly her health was delicate and a constant concern. She and her husband spent much of their time travelling, not least to find weather more congenial to her health. They were sailing in the Mediterranean in 1792 when she died.

‘While her coffin was being brought home by Graham through revolutionary France it was desecrated by an unruly mob of half-drunken men, who searched the corpse for gold in her teeth or rings on her hands. This incident profoundly shocked Graham and filled him with an unrelenting hatred of the French. Whilst he was in Britain burying his beloved wife, France declared war on Great Britain. He therefore set off to check first whether, in his mid-forties, he still had the mettle to be a soldier, and then to raise a regiment against them.

‘The 90th Perthshire Volunteers were raised in 1794 and by the following year had seen action in France. They acquitted themselves so well throughout the Napoleonic Wars that … they were re-designated as Light Infantry[5]. The 90th Perthshire Light Infantry served in the Crimean War 1854-1856 and Private Alexander became the first man in the regiment to win the recently instituted Victoria Cross[6].

‘In 1857 they were in India where at the relief of Lucknow, one of the most famous operations in the Indian Mutiny, the regiment won a further six Victoria Crosses there. After service in 1879 in South Africa during the Zulu War they were sent again to India.’

It is worth pausing here perhaps to look at this question: what is a Rifle Regiment; why all the fuss?

The website of The Rifle Brigade says[7]:

‘By the end of the eighteenth century several European armies included infantry specialised in the rolls of skirmishing and reconnaissance and the British followed the formation of the 5th Battalion of the 60th Royal Americans with the creation in 1800 of an Experimental Corps of Riflemen, its members hand-picked from other regiments, dressed in green and armed with the Baker rifle. Within four months of its first parade the new unit led an assault landing at Ferrol [Corunna, Spain] and two months later it ceased to be `experimental` and was gazetted under the new title of The Rifle Corps. Its first Colonel…was one of a handful of officers whose thinking shaped the Light Infantry of the Army.’

Later the Rifle Brigade (as it became) was grouped with the 43rd and 52nd (later the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry [see also below]) as well as the 60th (or King’s Royal Rifle Corps) in what was known as the Light Brigade[8].

These hand-picked soldiers equipped with a superior weapon – a rifle as opposed to a musket – and moving in double-quick time – established a new and a special force. They also added a new element to the battlefield: in depth reconnaissance.

As the rifle regiments were not part of the line there was no call for them to have colours to which they would in time of crisis be trained to rally. Thus was born the tradition of the elite, the special service troops of their day.

But this regiment has even older antecedents (though much younger than many of the regiments of the line, including the 26th). The Royal Green Jackets website says:

‘On 8th July 1755 a column of British redcoats under General Braddock, advancing to take Fort Duquesne on the Ohio River were ambushed by the French and their Red Indian [native American] Allies firing from concealed positions. The dying General’s last words ‘we shall learn better how to do it next time`, sum up the reaction at home to this defeat, for within a few months a special Act of Parliament had provide for the raising of the 60th Royal American Regiment of four battalions of American colonists. Among the distinguished foreign officers given commissions was Henri Bouquet, a Swiss citizen, whose ideas on tactics, training and man-management (including the unofficial introduction of the rifle and ‘battle-dress`) were to become universal in the Army only after another 150 years.

‘The new regiment fought at Louisburg in 1758 and Quebec in 1759 in the campaign which finally wrested Canada from France; at Quebec it won from Wolfe the motto ‘Celer et Audax’ (Swift and Bold). These were conventional battles on the European model, but the challenge of Pontiac`s Red Indian rebellion in 1763 was of a very different character and threatened the British control of North America. The new regiment at first lost several outlying garrisons but finally proved its mastery of forest warfare under Bouquet’s leadership at the decisive victory of Bushey Run.’

Thus we have the green jackets: forest skirmishers with a lighter and a more accurate weapon, dressed in camouflage and moving ahead of and separate from the infantry of the line. It was they who presaged the end of pitched battles and eventually the demise of fixed formations: the serried ranks of redcoats. Naturally they thought themselves superior in ever way to the heavyweight movers and thinkers of the line regiments.

It is no surprise then that they considered themselves an elite – even if nobody else did – nor that some of their officers earned the sobriquet of ‘rich, rude rifles’.

Such was the experience of the Army as a whole in the Crimean War that it was clear that major reforms were necessary. The performance of the Prussian army in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) reinforced the view that major reforms were not just necessary but overdue. They are usually referred to as the Cardwell Reforms[9] and it should be noted that though they are usually associated with regimental reorganisations they encompassed a great deal more including the abolition of the purchase of commissions and many changes to terms of enlistment for soldiers, as well as the abolition of corporal punishment.

The eventual outcome (post 1881) was that all infantry regiments were given two battalions, the idea being that one of these would serve at home whilst the other served abroad, usually in India. Recruits for both would be trained at a Regimental Depot in the heart of the regimental recruiting area, and from there drafts of trained men would be sent to both battalions. But these reforms took time and it is only through unravelling the various stages that they went through that we are able to see how the 26th and 90th came to be joined.

The first changes took place in 1874 when all regiments were grouped together in combined depots with the regiments there being paired. There were normally two pairs, four regiments, to each depot. The home regiment of the pair was then responsible for providing drafts of trained men for the overseas one.

A new depot was established at Hamilton in Lanarkshire to serve not just four regular regiments but also two battalions of militia and five of the Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers[10]. The 26th (Cameronians) were paired there with the 74th Highlanders and the 73rd Highlanders were paired with the 90th (Perthshire Light Infantry).

The Zulu War of 1879 then starkly pointed up the inadequacies of this pairing system and there was a new mood to push through even greater reforms so that, instead of having paired regiments, full-blown amalgamations would take place, with the outcome that each new regiment had two halves ie two battalions. Only then would the necessary flexibility be obtained.

The Regimental History Volume I[11] says:

‘In 1876 the Stanley Committee, set up to report on ‘the general working of the present depot system’ recommended the formation of territorial regiments. Five years later the government decided to carry out its recommendations. A committee presided over by the Adjutant General[12] worked out a scheme for constituting and naming the territorial regiments[13], involving in some cases a readjustment of the ‘linking’.

‘Under this scheme the 26th was divorced from the 74th and joined with the 90th Light Infantry to form The Scotch Rifles Cameronians.’

Lieutenant Colonel David Murray in A Tribute to The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) has written[14]:

‘Among the more surprising amalgamations of the 1881 reorganisation of the infantry was that of the 26th Cameronian Regiment with the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry. Another surprise had been the creation of two localised regiments of ‘Rifles’, the Royal Irish Rifles and the Scotch Rifles (Cameronians) changed smartly to the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) a couple of months later.

‘The 26th were no doubt pleased that their ancient name was to be retained, but the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry was not at all amused at being forcibly connected with a steady, not to say dull, old line regiment with whom it had no previous connection[15]. Indeed, the 90th claimed to have been raised and trained as Light Infantry several years before the concept had been introduced into the British Army, although the title had not been formally granted until 1815. …

‘Field Marshal Lord Wolseley, who served in the 90th, makes no mention of their origin in his memoirs, claiming memorably that ‘[The officers of my regiment] … thought themselves socially superior to the other regiments of the Line, which were always spoken of as ‘Grabbies’. Many were well connected, and some were well off. … It was in every respect a home for gentlemen, and in that respect much above the great bulk of line regiments.’[16]’

‘Appendix A to General Order 41 of 1 May 1881 set out the Ellice Committee’s first proposals. It shows that the 26th and the 90th were both thrown into the Scotch broth pot and no doubt took pot luck, the 26th emerging with the 74th as The Scotch Rifles’ while the 90th were to be paired with the 73rd as The Clydesdale Regiment’ (Light Infantry). While the proposed pairings for the Highland regiments appear to have been based on the compatibility of their facing colours (42nd with 79th, both blue; 71st and 78th, buff; 72nd and 91st, yellow; and 92nd and 93rd, also yellow) those envisaged for the remaining Scottish regiments have no common link the facings of the 26th being yellow, the 74th white; the 73rd green, and the 90th buff.

‘However, the expected row ensued; these first leaked pairings were dropped; and those regiments which were part of the Scottish scene until 1958 eventually appeared.’

All of this is a bit breathless. Nor indeed does the Regimental History really help with enough or better detail. It is worthwhile therefore to go back and to dig a bit deeper.

Study of papers lodged in the National Archives throws up a lot more detail and as a result is worth quoting. In a Memorandum of 1880[17] we find:

Army Organisation – Infantry Only – Normal

‘Part I. The double or linked battalion system was introduced for the purpose of facilitating foreign reliefs. … This [system] presupposes that of the two linked battalions, one is abroad whilst the other is at home. In practice, however, this has never been invariably the case. …

‘Part II. A Synthesis. … Therefore the battalions were linked but the desired object of the one battalion serving abroad, whilst its fellow is at home has not been attained. The Committee, in linking the battalions, appear to have found that it was impossible … to have regard to the historical relationships of the various battalions, which formed one of the features of the linking, and yet to link them, or that their future respective periods of service at home and abroad would admit of the one returning home at the time the other had completed its tour of home service. Failure in this matter is one of the causes of the alleged failure of the existing system.’

These were some of the considerations which led eventually to the Report of the Committee on the Formation of Territorial Regiments[18] as proposed by Colonel Stanley’s Committee and dated December 1880.[19]

Here we read:

‘…

‘3. There are several reasons for considering a re-adjustment of the present coupling of regiments as desirable. In some cases traditional sentiment, in others local considerations, in others again questions of clothing and uniform point to the fact that certain alterations in the existing linking would be attended with advantages. [Here reference is made to two couplings only, the first being to that of the 43rd and 52nd based on their long and close ties stemming from the Peninsular War 70 years earlier. See also above.] … while on the other hand, the 26th Cameronians, a lowland and originally a Covenanter Regiment, is linked to the strongly Highland 74th. As the 26th was originally raised for the purposes of opposing the Highlanders, it is manifest that its regimental traditions, and the feeling which these traditions always engender, must clash seriously with those of the 74th.’

Before passing on to the all-important Appendices to this report it is worth pausing to note that although the committee interviewed a number of officers from various regiments none was interviewed from the 26th (or 90th) and the word of an officer of the 74th was taken as being enough. He was not wrong.

Appendix I (of the above committee report) has a table showing the composition and uniform of the proposed territorial regiments. It notes the old and the new uniforms and facings colours.

Appendix II is headed:

‘Table Showing Territorial Regiments in Alphabetical Order’

It then lists them under the geographical locations of their depots:

‘England, Wales, Scotland ‘

And here we have it: a new entity entirely:

‘Rifle Regiment

The Scotch Rifles, 26th and 74th, Hamilton’

And then (under Ireland), similarly[20]:

‘Rifle Regiment

The Royal Irish Rifles, 83rd & 86th, Belfast[21]’

This is the first mention we find of these new Rifle Regiments and what immediately strikes today’s reader is the surprise that the honour is accorded first to the 26th and without any reference to the 90th. We must return to this but it is worth completing first our study of this report and its final part:

‘Appendix III

Table Showing Proposed New Linking’

Here for the first time we see:

‘Rifle Regiment

The Scotch Rifles, 26th and 90th, Hamilton’

Note: this was in Appendix III of the same Report which mooted Scotch Rifles for the first time, but with a different conjunction, the 90th having now replaced the 74th for this favour.

So we have reached home base and arrived at the point we would have expected, but not from the route or direction we had expected; not by any means. It is no exaggeration to say that the discovery of this document stands on its head what has come to be the received wisdom and the accepted folklore, both in the Regiment and shared by Lieutenant Colonel Murray and others, about the naming of the regiment and the pairing of its components.

One must pause momentarily to dismiss any thought that chicanery of any kind entered into this. It is fanciful to suppose that Appendix II is just window dressing. It seems beyond doubt that what we read is what was actually planned, no matter how inconvenient the truth.

The present writer helped to perpetuate the myth as recently as an article in the Covenanter of 2005. No doubt was cast on his views: indeed the general opinion amongst his (albeit limited) readership seemed to be that he had got it about right. He wrote:

‘Historically there was always a tradition of very senior officers being produced by or associated with the Regiment, though in truth, up to 1881, this was based almost entirely on the 90th. They had the distinction of producing no fewer than two Commanders-in-Chief of the army and two Field Marshals – Sir Garnet Wolseley was both. Their founder was himself one of the most distinguished. He was Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Graham of Balgowan, who later became Lord Lynedoch and was the Duke of Wellington’s ablest commander[22]. Others were General Sir Rowland (later Lord) Hill, like Graham, ennobled for his leadership in the Napoleonic wars (Commander-in-Chief 1828-1842) and Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood VC (Acting Commander-in-Chief in 1890).

‘Another distinction which the 90th had: three VC’s were to command the Regiment.

‘Lest it seem that the military virtues were a bit one-sided, or that the 90th were marrying a bit beneath themselves, the sheen and shimmer of the 90th should be seen against the deep lustre of the 26th. Not only had they 200 years of distinguished service to the Crown – everywhere from Marlborough’s Blenheim to Napier’s campaign in Abyssinia – they had also earned themselves an impressive record in the soldierly skill of rifle shooting. In the Army in India they came third in 1873 and first the following year. Back on home service they competed in the Army Championships at Bisley coming third in 1876 and first in 1877. Indeed the Regimental History (Volume I) goes so far as to suggest: ‘Perhaps its [recent?] success in marksmanship … was responsible for this decision [to name the new regiment The Scottish Rifles and to make the 26th the 1st Battalion]’.

‘Maybe that is not such a long shot. It is said that Queen Victoria personally decreed that the 90th be chosen for promotion to become a rifle regiment following their excellent service as Light Infantry.’

What we see now, however, is that it is the 26th who were granted the distinction, the promotion, to the elevated status of Rifles. The designation of Scotch Rifles predates the uncoupling of the 26th with the 74th. It was an after-thought that the 90th be joined with them. We will return to this later.

In the light of this we must examine again the basis for the original decision. Above one sees the first mention of the idea that the 26th were selected for their marksmanship. There is another reason too why they might have been selected. Of all of the regiments of the line, the 26th was the senior which had only one battalion. All of the other 25, including the 1st (later Royal Scots) and the 21st (Royal Scots Fusiliers) named as being Scotland-based, had two or more battalions already and so were in no need of linking or pairing, far less did they have to be turned into two-battalion regiments. (The 25th – later King’s Own Scottish Borderers – were from 1782 to 1887 considered an English county regiment before their recruiting area was moved to the Scottish Borders. From 1860 to 1948 they also had two battalions.)

If indeed the decision was taken (by whom and for what purpose is less important) to have Scotch Rifles, why would the planners look further than the senior single battalion? If they were also the pre-eminent rifle shots the case was closed.

For the decision regarding the final name we must wait a bit longer, and there too a story attaches itself. But in passing, it should be noted that whatever else came out of all of the discussions, the name of the Perthshire Light Infantry Volunteers (and all of its variants) was the one which was lost, together with any lingering links to its historical heartland in Perthshire. The new 2nd Battalion were content to call themselves the 2nd Scottish Rifles, indeed it was only the 1st Battalion which clung to their old name of Cameronians. Other battalions such as the 5th were always 5th Scottish Rifles.

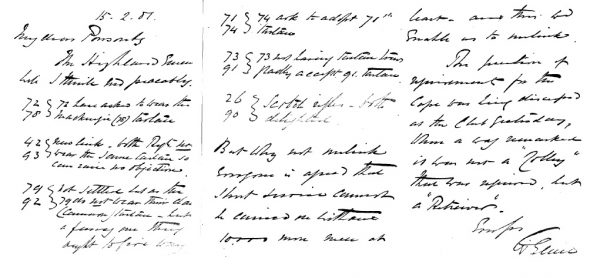

We should now turn to another source for some background and for that we are indebted to Her Majesty The Queen for her gracious permission to quote from papers in the Royal Archives[23]. The first one of interest is a letter from General Sir Charles Ellice, the Adjutant General,[24] to Queen Victoria’s Private Secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, in which he writes:

‘15.2. [18]81

My dear Ponsonby

[And here he gives various options for pairing Highland regiments but note: it seems that the interest now was not in the colours of their tunic facings – see above – but on which tartan they would each agree to wear.]

…

72]

78] 72 have asked to wear the Mackenzie (78) tartan.

42]

93] New link. Both Regts agree to wear the same tartan so can raise no objection.

79]

92] Not settled but as the 79th [will?] not wear their clan (Cameron) tartan …

71]

74] 74 ask to adopt 71st tartan

73]

91] 73 not having tartan trews gladly accept gt [government] tartan.

26]

90] Scotch rifles – both delighted.

…. [etc] [25]

This is reproduced at Figure 1.

What seems quite obvious from this (and borne out later, see below) is that the last was the most straightforward and presented no complications to anyone. The comment about their sentiments – ‘delighted’ – is telling.

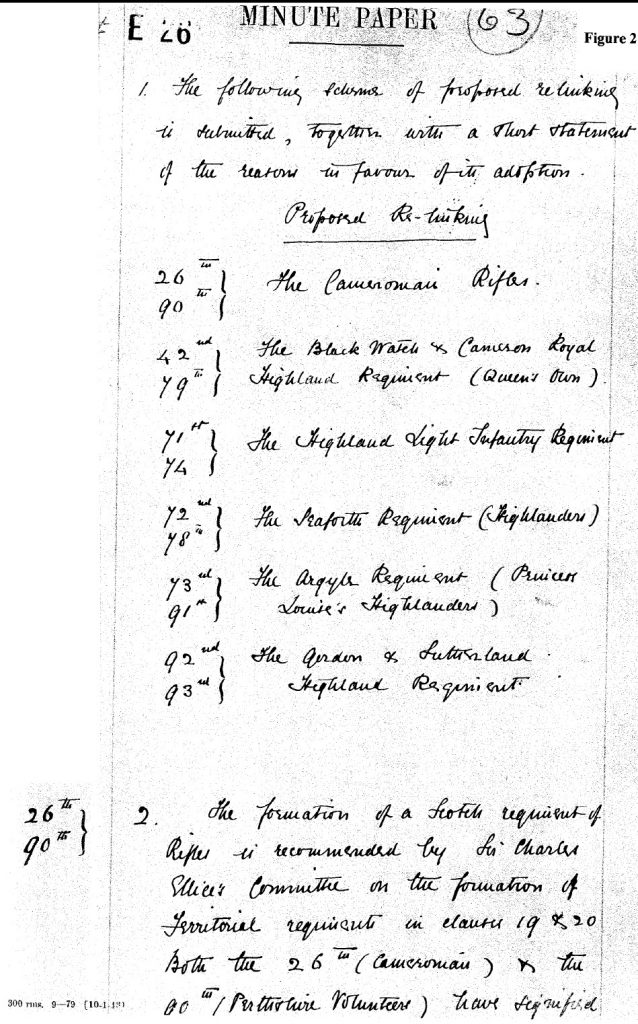

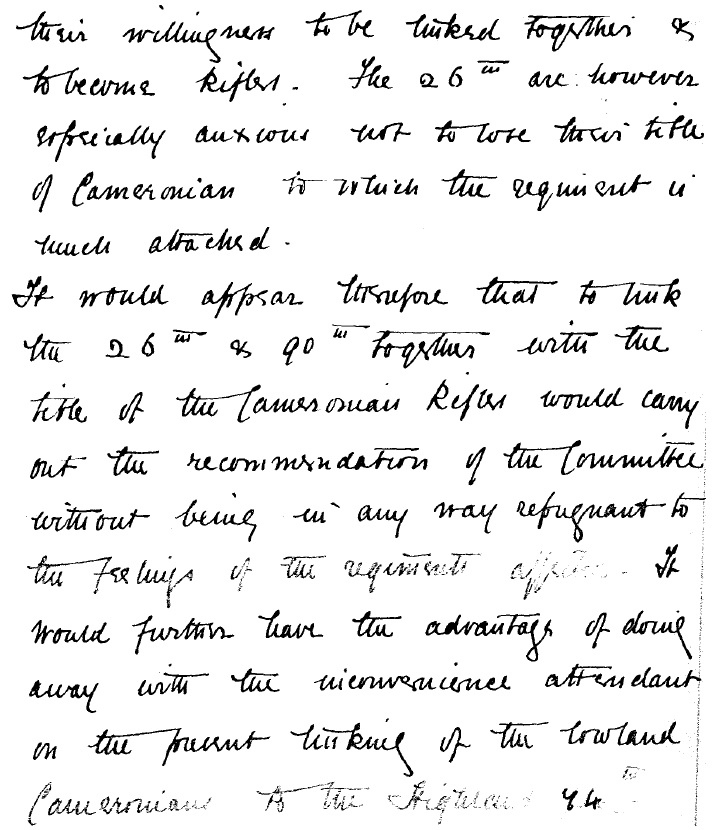

However we are not out of the wood yet – and there is plenty of that. The next extract from the Royal Archives is a memorandum by Ellice dated 28 February 1881 (just two weeks after his letter above to Ponsonby). This has yet another set of combinations and permutations, with one exception, and that is the first he lists:

‘MINUTE PAPER

1. The following scheme of proposed relinking is submitted, together with a short statement of the reasons in favour of its adoption.

Proposed Re-thinking

26th}

90th} The Cameronian Rifles

42nd}

79th} The Black Watch & Cameron Royal Highland Regiment (Queen’s Own)

71st}

74th} The Highland Light Infantry Regiment

72nd}

78th} The Seaforth Regiment (Highlanders}

73rd}

91st} The Argyll Regiment (Princess Louise’s Highlanders

92nd}

93rd} The Gordon & Sutherland Highland Regiment

‘2. The formation of a Scotch regiment of Rifles is recommended by Sir Charles Ellice’s Committee on the formation of the Territorial regiment in clauses 19 & 20. Both the 26th (Cameronians) and the 90th (Perthshire Volunteers) have signified their willingness to be linked together & to become Rifles. The 26th are however especially anxious not to lose their title of Cameronians to which the regiment is much attached.

‘It would appear therefore that to link the 26th & 90th together with the title of Cameronian Rifles would carry out the recommendation of the Committee without being in any way repugnant to the feelings of the regiments affected. It would further have the advantage of doing away with the inconvenience attendant on the present linking of the lowland Cameronians to the Highland 74th.’

‘3.’ […etc And he goes on to explore various other arguments about all of the other pairings.] [26]

This is reproduced at Figure 2.

The point to note here is that once again the 26th / 90th arrangement seems the easiest settled, not least because of the feelings in the regiments. It is interesting to note that the 90th would appear to be satisfied, even then, with the proposed new title. To be Rifles was presumably enough, and of that too, more later.

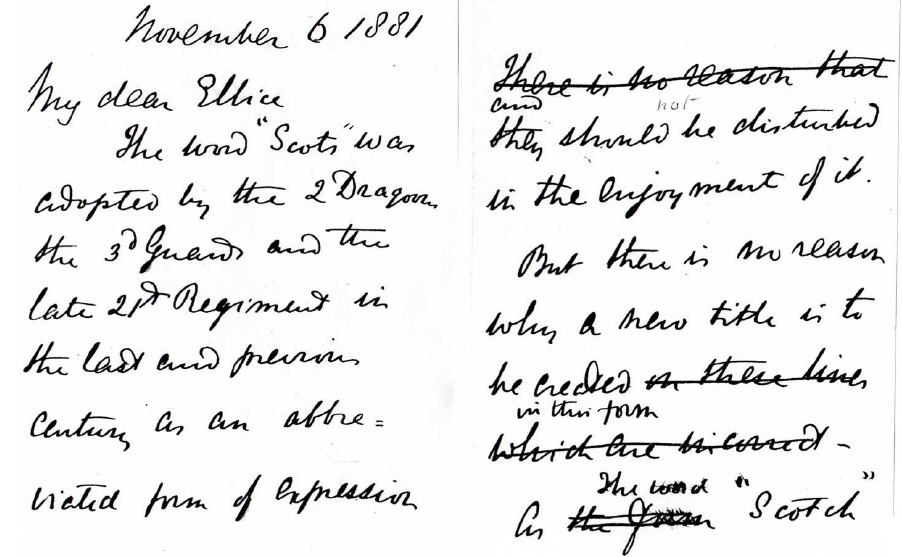

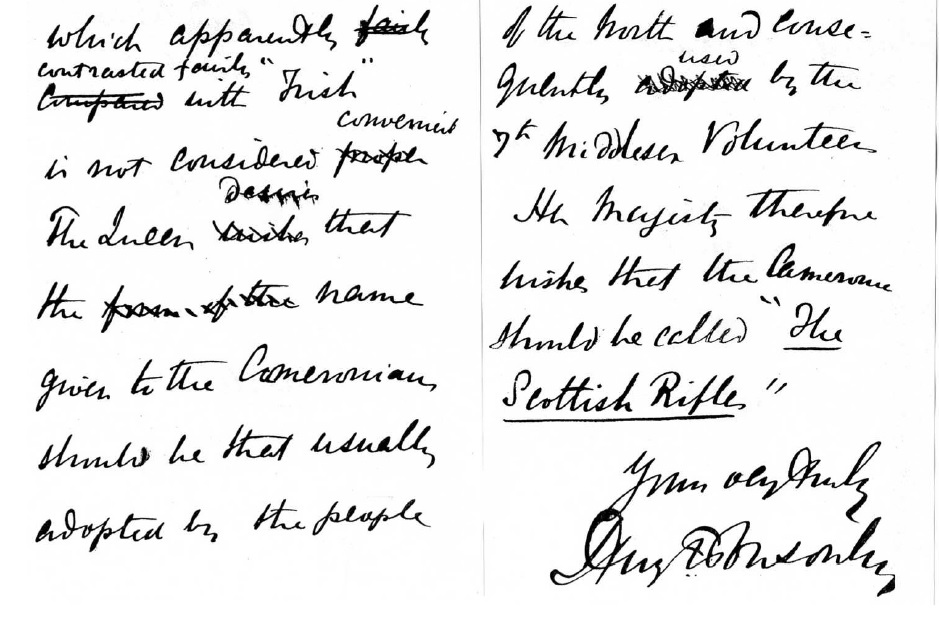

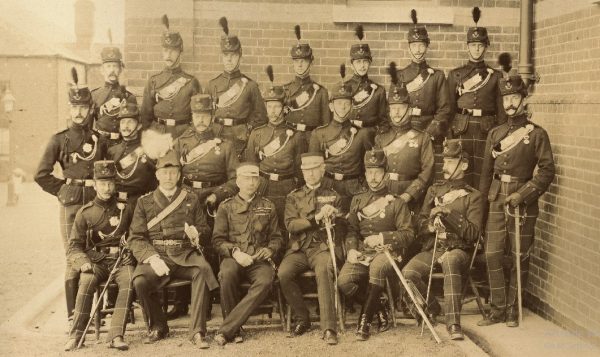

The next important correspondence in the Royal Archives is a letter from Sir Henry Ponsonby to General Sir Charles Ellice:

‘November 6 1881

‘My dear Ellice

‘The word “Scots” was adopted by the 2 Dragoons [Greys] and the 3rd [Scots] Guards and the late 21st Regiment [Royal Scots Fusiliers] in the last century as an abbreviated form of expression and they should not be disturbed in the enjoyment of it.

‘But there is no reason why a new title is to be created in this form.

‘The word “Scotch” which apparently contrasted fairly with “Irish” is not considered convenient. The Queen desires that the name given to the Cameronians should be that usually adopted by the people of the North and consequently used by the 7th Middlesex Volunteers. [What this refers to cannot be guessed.]

Her Majesty therefore wishes that the Cameronians should be called “The Scottish Rifles”

Yours very truly

Henry Ponsonby’[27]

This is reproduced at Figure 3.

And so the whole matter was eventually settled. There was still some way to go to get a final version of the other pairings. These were first proposed in a memorandum sent by Sir Charles Ellice with a letter dated 23 February 1881 and it is worth quoting here as it gives the pairings as eventually adopted ie those which survived until 1958. Note however that the locations for their depots were not always the final choice

‘Scheme for the coupling of Scotch Regiments

26}

90} Scotch Rifles (Cameronians) – Hamilton

42}

73} Black Watch – Perth

71}

74} Highland Light Infantry – Hamilton

72}

78} Seaforth Highlanders – Inverness

79}

2 Bns Cameron Highlanders – Aberdeen

91}

93} Argyll & Sutherland – Stirling

92}

75}[sic] Gordon Highlanders – Fort George

‘2.….

‘3. The kilting of the 73rd, 75th, and 91st Regiments.

…[etc] and later

‘If this coupling be adopted for Scotch Regts, that of the English becomes an easy matter’[28]

This last, a most telling comment! Plus ça change…

The details concerning other regiments need not detain us here. What is to be noted is that in the course of 1881 the necessary decisions had been made and the course was clear for the new regiment, The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

Lieutenant Colonel Murray makes an interesting comment when he says (apropos the choice of the 90th to accept union with the 26th):

‘As always there were those who claimed that this apparent mismatch was the result of stupidity, ignorance, or simply a mistake.’

He then goes into some detail about the 99th who had been re-raised as the Lanarkshire Regiment but who eventually found themselves tied to the 62nd (Wiltshire) Regiment. He makes various suggestions of what might have been. He goes on:

‘Unfortunately for those who believed in the conspiracy theory the truth is more prosaic.’

He continues with the passage quoted earlier. But this writer is of the opinion that the truth is far from prosaic and indeed there was, in his opinion, almost certainly an amount of ‘fixing’ going on behind the scenes. It seems much more likely that strings were being pulled and committee-men squared by reasoned persuasion. Considering two key figures this seems not just possible but highly likely.

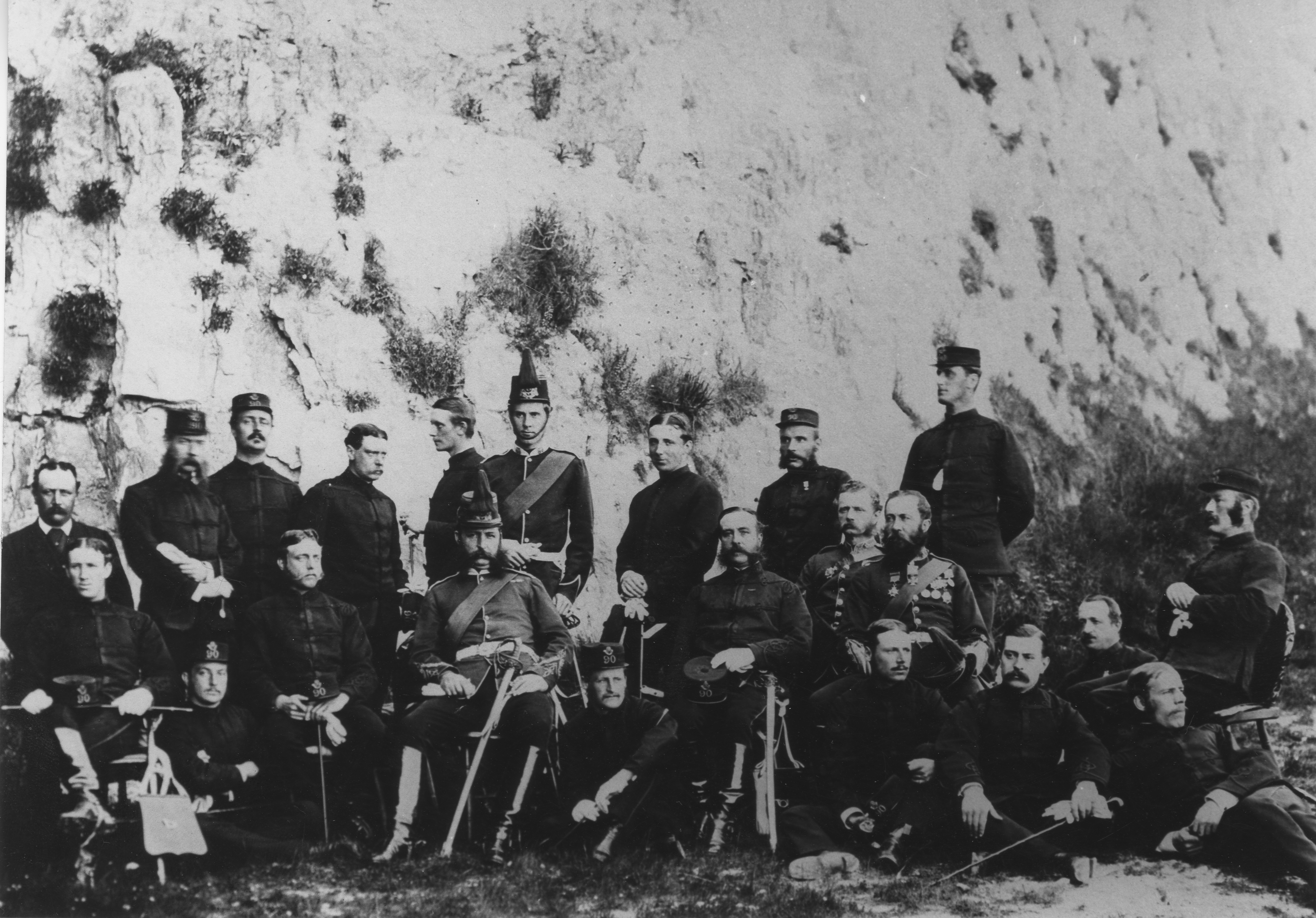

As noted above, the 90th Light Infantry boasted two ex-officers who were the outstanding soldiers of their time and whose careers were inextricably intertwined. This was no accident: the older chose and nurtured the younger. They eventually became Field Marshal Sir Garnet (later Viscount) Wolseley and Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood VC. The former was Commander in Chief 1895-1900 and, when he had to retire through ill health, he was succeeded temporarily by the latter who was then the Adjutant General.

For much of their careers they were, along with the rest of ‘Wolseley’s Circle’ accused of conniving and colluding. It is well known that Wolseley was at the heart of the Army reforms. It is perhaps naïve to think that Wood was not in some way implicated as well. One might go further: Wood has been described as, amongst other things, a towering snob. He also had the ear of Queen Victoria.

The Regimental History says, and it is often quoted, that Queen Victoria herself decided that there should be Scotch (as well as Irish) Rifles but the source of this has not been traced even in the Royal Archives. We have already seen that it was Queen Victoria’s choice that ‘Scottish Rifles’ be used instead of ‘Scotch Rifles’. But that is a long way from proving (or otherwise) the assertion that she personally decided on the formation of the two new rifle regiments. It seems fanciful to suppose that she woke one morning and, looking out on the Great Park at Windsor (or even on the hills of her beloved Deeside at Balmoral), said to herself, “I know: let’s have some Scotch Rifles!” Does it not seem more likely that an interested party made a comment sufficient for the Queen to see the wisdom (suitably admired by all) of such a choice?

Garnet Wolseley was the outstanding soldier of his day. His fame was such that the phrase ‘All Sir Garnet’ entered the language as a description close to that of ‘all shipshape and Bristol fashion’ or ‘just so; just as it should be’. He earned immortality as the model for Sir WS Gilbert’s ‘Modern Major General’ in the operetta The Pirates of Penzance. He first came to prominence in the public (as opposed to the purely military) domain when he returned triumphant after his campaign in the Ashanti War. On his return, in March 1874, he was summoned by Queen Victoria to Windsor. A biography of him says[29]:

‘The Queen reviewed the general’s little army. … After inspection [they] formed a hollow square. Sir Garnet dismounted and came forward to be invested by Her Majesty with the Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George and of a Knight Commander of the Bath.

‘That evening Sir Garnet was received in the Houses of Parliament where the benches and galleries were crowded with the nation’s leaders. … The general was given a grant of £25,000* approved unanimously in the House of Commons, and promoted to the rank of Major General ‘for distinguished service in the field’.

‘Pressure was put on him to accept a baronetcy [which he declined]. … If it had not been for the fall of the Gladstone government he was sure he would have been offered a peerage[30].’

He was 39 years old. He had already been knighted (KCMG), as a Colonel, four years earlier.

One of the officers on parade that day was the 36 year-old Evelyn Wood VC. In his memoirs he wrote[31]:

‘Soon after our return from the West Coast [of Africa] we were honoured by a command to Windsor, officers of the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and upwards only being invited to dine at the Royal table and to remain the night at the Castle.

‘… I received three month’s leave for the recovery of my health, at the end of which I had hoped to join the Headquarters of my battalion at Dover, but the Lieutenant Colonel then in command did not wish to have a full Colonel with him, who would very often, in Field operations, have command of the brigade, and persuaded my brother-officer and junior, Major Rogers[32], to come from the Depot to Headquarters.’

I should think not! But this small extract from his memoirs is worth quoting. It is vintage Wood.

He had joined the Navy first and was serving on-shore in an army role in the Crimea when he first came to prominence. Aged just 17, a Midshipman, he was recommended for a VC for his actions at the storming of the Redan in 1855[33]. Within months he had resigned the Navy and been awarded a commission without purchase in the 13th Light Dragoons. Having transferred to the 17th Light Dragoons he won his VC the following year when serving on detachment with the 3rd Light Cavalry. He then raised and commanded the 2nd Central India Horse. By 1862 he had transferred to the 73rd Regiment (later 2nd Battalion The Black Watch) and then from them to the 17th Foot. After various staff appointments he purchased a majority in the 90th. This was his last move. His last regimental service was in command of the 90th.

Space here is too short to do justice to his extraordinary career. This is a summary of a few of its highlights:

1871: Major, 90th Perthshire Light Infantry.[34]

1873-74: On Special Service in Ashanti (see above)

1874: Whilst waiting for a place at Staff College, qualified as a barrister in London[35].

1878-79: Commanding Officer 90th The Perthshire Light Infantry.

1878-81: Commanded a column in South Africa. Mentioned in Dispatches 14 times.

1879: Awarded KCB and promoted Brigadier General.

1881: Awarded GCMG and promoted Major General (note well the year).

1882: As Sirdar [Commander-in-Chief] raised and led the Egyptian Army.

1889-93: In command at Aldershot: (Lieutenant General 1890).

1893-97: Quartermaster General.[36]

1895: Promoted General.

1897-1901: Adjutant General

1900: Acting Commander-in-Chief.[37]

1903: Promoted Field Marshal.

1920: He died at Harlow, Essex. His memorial is in St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

The Ashanti campaign was the occasion on which Wood joined the Wolseley circle. Wood’s description of his recruitment is:

‘Sir Garnet’s original intention had been to take two battalions each about 1300 strong, made up of picked men from the most efficient battalions in the Army at home, each of which was to furnish a company under its officers, and I was to have command of one of these.’

Those who criticised Wolseley’s modus operandi did so on the basis that it smacked of favouritism. Those in the circle would have pointed out that it was merit, ability and reputation which mattered. All that matters here is that Wood joined this charmed band and was to remain a part of it for the rest if his career – which saw them both at the top of the tree twenty years later.

So in 1874 we see them both returning triumphant from West Africa to be received as heroes. But it is where they were seven years later which is of interest and import. Wolseley, as we have seen, attracted attention early on as a successful commander in the field. There was another side to him however. His biographer says:

‘On May 1st 1871 Sir Garnet was appointed Assistant Adjutant General at the insistence of Cardwell, who was to regard him as his chief military advisor. To Wolseley it was the opportunity of a lifetime. Ever since his experiences in the Crimea he had been appalled by the shortcomings of the military system. With each succeeding campaign a gnawing impatience for reform grew in him.

‘… Strangely different in so many ways the politician and the soldier developed an intimate friendship and worked efficiently as a team – Cardwell with the blue-prints and Wolseley giving them practical shape.

‘… After the purchase struggle [the abolition of the purchase of commissions which had been fiercely opposed in many, including royal, circles] Wolseley busied himself with working out the details involved in the problem of regimental reorganisation, another of Cardwell’s sweeping reforms.

‘… As a reward for his services in resuscitating the army from the suffocating effects of prejudice and tradition Cardwell arranged for Wolseley to command the military expedition to be sent against the ferocious Ashanti in West Africa.

‘… The General [Wolseley] was limited to the selection of 36 staff and special service officers. In making his choice from among the many volunteers he looked for thinking soldiers who had more than their fair share of courage.

‘… This was the Ashanti Ring. It was a splendid staff of able, and in some instances, brilliant men. … He believed the surest way to succeed was to surround himself with the very best officers he could obtain.’

No doubt Wood thought himself eminently suited on every count.

Of this time (1871) Wolseley himself wrote, on being posted to London[38]:

‘… Horse Guards, [was] then the Headquarters of the Army[39]. That wonderful institution, which had forgotten nothing and had learnt nothing[i] since Waterloo, was sadly behind the times in every way.

‘… In common with a number of our educated officers in 1871, I knew what was wrong in the Army and I did not hesitate to expose it. I preached reform in and out of season. … I was impatient and in a hurry: my nature would not brook the sapping of a regular siege: I wanted to assault the place at once, and I did so.

‘… But my best chance was that I found in office a great Minister at the head of Army matters: a clear-headed, logical-minded lawyer [Cardwell].’

This was his first bite at reform. Thereafter, as we have seen he was rewarded with command in the Ashanti Campaign. For his next posting he expected to be made Adjutant General to Lord Napier in India but instead was called back to the War Office to become Inspector General of Auxiliary Forces. He had no sooner embarked on that than he was once more sent to Africa. By 1878, promoted to Lieutenant General, he was High Commissioner of the newly acquired island colony of Cyprus.

By 1879 the situation in South Africa was slipping out of control and ‘… the Ministry wanted him to clean up the mess in Zululand’[40]. To do so:

‘… They selected a soldier-administrator who boasted of unbroken success and considerable knowledge of South African affairs, Sir Garnet Wolseley. Appointed to the local rank of General he was invested with supreme power as commander of Her Majesty’s forces in South Africa and High Commissioner for South-East Africa.

‘… When Disraeli [Prime Minister] imparted the news to Wolseley he asked how soon he could start. “By the four o’clock train this afternoon if you wish it”, was the characteristic reply.’

Before leaving South Africa (in the spring of 1880) he learned that he had been nominated Quartermaster General[41].

‘In England Wolseley learned that his popularity had reached new heights. …He had proved himself master of the small war. …The press sang his praises and, borrowing Disraeli’s fanciful appellation, dubbed him “our only General”.

‘He returned to the War Office a little older [though still only 47] and somewhat saddened, prepared to act as a flesh-and-blood battering ram to break down the wall of prejudice, inertia and stupidity in order to create a more efficient army.

‘… The introduction of the territorial system produced more friction and hard feelings than any single major reform. To be linked with another battalion, as Cardwell conceived it, was bad enough, but to be permanently welded with a subsequent loss of historic numbers, traditions, and exclusive battle honours won with blood was an intolerable innovation to most soldiers. Even the treasured regimental facings were to be obliterated. … The Quartermaster General respected the regimental spirit that had kept the British soldiery together for two centuries but he now wanted to see this collection of regiments transformed into an army.’

This is where we find Wolseley in 1881, in the thick of reform and at the heart of the War Office where once more he could pull the levers if not of power at least of influence. It did not endear him to the Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of Cambridge, or to the C-in-C’s cousin Queen Victoria. They felt that the Army should remain under the direct and personal control of the sovereign. Times had however already changed and the real power had already shifted to the politicians. The last vestige of regal power had made its irrevocable transition to full constitutional monarchy.

In 1882 Wolseley was promoted to General and became Adjutant General. With intermittent breaks to command campaigns in Egypt and the Sudan he remained there until 1890. So from 1880 to 1890 he held the two key appointments in the War Office. It is hard to exaggerate the influence he had then over the army’s management and organisation. Has any other officer ever held these two pivotal appointments consecutively for longer?

From 1890 to 1895 he was C-in-C Ireland during which time he was promoted Field Marshal. He finally reached the peak of his profession when in 1895 he succeeded the Duke of Cambridge as the Commander-in-Chief. Merit had finally triumphed.

Meanwhile where was Wolseley’s prodigy, Evelyn Wood VC?

The campaign in South Africa saw him up to his neck in action as usual. The fact that he was mentioned in dispatches no fewer than fourteen times speaks for itself. He was ‘nominally’ (his own word) in command of his Regiment, the 90th, though his energies were directed towards commanding a column (or flank). For his actions he was promoted Brigadier General and appointed KCB (1879). By January 1881 he was needed again. Let him take up the story in his own words:[42]

‘On 4 January I received a note from the Military Secretary asking me in the name of the Commander-in-Chief if I would return to South Africa to serve under Sir George Colley [General and High Commissioner, in succession to Wolseley[43]], to whom I was one senior in the Army List, and requesting me to go to London to discuss the question. I agreed to go out on the Adjutant General’s observing, “Your rank, pay and allowances will be the same as at Chatham [where he was District Commander].”

‘In a Letter of Service received on the 6th it was stated that I was going out as a Colonel on the Staff. This I declined by telegraph, recalling the previous day’s conversation, and was again ordered to the War Office. Though the Adjutant General predicted I should regret it I maintained my position. In the result a fresh Letter of Service was handed to me with the rank of Brigadier General which I had held at Chatham and also when I left the Colony 18 months earlier, having command in two campaigns and five fights a strong brigade of all Arms.

‘Lord Kimberley [Colonial Secretary] sent for me and explained his views of the question of the Zulu and Swazi states after the annexation had been annulled, which he gave me to understand he already accepted in principle. I took leave of Her Majesty the Queen, who was very gracious to me, on 7th January, and sailed on the 14th, reaching Cape Town on the 7th February.’

There are two points to note here. The first is that it seems inconceivable that when Wood presented himself at the War Office to discuss his future role with AG he did not consult his mentor, Wolseley, sitting next door in the office of QMG. Their careers were too intertwined for him not to; it’s not how Wolseley operated anyway. The second point is his reference to the Queen, and we shall return to that because it is not without importance.

One should also bear in mind the dates. This is exactly the time (January / February 1881) when AG and his committee are putting the final touches to their recommendations to HM through her Private Secretary, Ponsonby.

After a year in South Africa, Wood returned to the command of his District at Chatham. He writes[44]:

‘I had many reasons to be grateful to Her Most Gracious Majesty the Queen who invested me shortly after my arrival with the Grand Cross of St Michael and St George.’

But his time in England was all too short. By August he had been given command of the 4th Brigade and embarked for Alexandria in Egypt.

‘… Her Majesty, coming on board [SS Catalonia] to say goodbye to us. She embraced my wife and was very gracious to me. She had honoured me with a long interview in July, when I was commanded to Windsor, and treated me with a condescension for the memory of which I shall be ever grateful.’

By Christmas 1882 he was back in Cairo and, appointed Sirdar (or Commander-in Chief), was charged with raising an Egyptian army. In August the following year he took two month’s leave and returned to Britain.

‘Her Majesty the Queen was graciously pleased to command me to stay at Balmoral[45] and took much interest in the Egyptian Army.’

The point of all of this is not just to trace Wood’s extraordinary career – fascinating as it is – but to look at the way in which he enjoyed easy and regular access to the Queen. Considering that even now he was but a 50 year-old Major General (albeit weighed down with myriad decorations and honours, starting with his VC), his access and his easy relations with her were highly unusual. From where did that stem, and what were the implications?

There are several strands to this story. Bearing in mind Wood’s character it might not be wise to assume that he is a totally disinterested party. Putting it mildly one might assume that he perhaps put to good use what connections he had with the Queen. He probably felt that, having been born into a family of courtiers, he already had the right to put one foot on the steps of the throne. He wrote:

‘My father, John (later Sir John, Bart) Page Wood, Clerk in Holy Orders, … was educated at Winchester and Cambridge. He took his degree early in 1820 and was immediately appointed Chaplain and Private Secretary to Queen Caroline[46].’

In South Africa in 1879 he met the Prince Imperial[47] who was serving there. A few weeks later and the young prince was dead. Later that year Wood was back in London.

‘When Her Imperial Majesty the Empress Eugénie [mother of the Prince Imperial] read in the newspapers the account of the Fishmongers’ banquet on the 30th September[48], and the allusion to her noble son beautifully expressed in Shakespeare’s language*, she sent for me and after several prolonged interviews I was commanded to Windsor where Her Majesty [Queen Victoria] was graciously pleased to honour me with the charge of the Empress on a journey she was undertaking to the spot where her gallant son perished. The Queen enjoined on me the greatest care for the safety of her Sister [they were not in fact related in any way], and I replied that I could only accept full responsibility if H.I.M. the Empress would follow my instructions as if she were a soldier in my command. This was arranged and on the 25th March the Empress sailed from Southampton for Cape Town and Durban.

‘Her Imperial Majesty [the Empress] had sent me a cheque for £ 5,000· desiring me to purchase everything required and to defray all charges.’

For the next three months Wood conducted her on an 800-mile tour of South Africa, including the site of her son’s death, often driving the horses himself. In total he was away for six months, all of it taken as unpaid leave. No doubt he thought it worthwhile none-the-less.

‘After giving a personal report of the journey to Her Majesty [Queen Victoria], for which purpose Lady Wood and I received a command to Osborne[49], I resumed my work at Chatham.’

This is the summer of 1880. This is exactly when the committees are meeting in the War Office and all of the reorganisations are being planned. His final comment, at the end of his autobiography:

‘In the evening of the 22nd January [1901] Her Imperial Majesty the Queen [Victoria] died, and beside my personal grief, I realised I had lost a Patroness who since the Zulu war [1878-79] had treated me with the most gracious kindness’

Amongst other things Queen Victoria was godmother to the Woods’ daughter, Victoria, and he tells us that on the death of his wife ten years earlier:

‘Nothing could be more touching than the gracious solicitude of Her Majesty the Queen, who offered to come to Aldershot to see Lady Wood before she died. … Her Majesty sent me a beautifully expressed letter of compassion …’

Nothing at all has been traced to suggest that Wood used his influence and proximity to Queen Victoria to further the cause of the 90th, but there must remain a suspicion that if anyone was to whisper in her ear that Wood’s regiment should be advanced from Light Infantry to Rifles, he was at least as well placed as anyone to do so.

And so what, in the end, are we to conclude about the whole business of the fusion of the 26th and the 90th?

It is beyond doubt now that it was the 26th who were first selected to become the Scottish Rifles. This may have been based on their renowned competence as rifle shots or on their seniority, or both.

The 90th had no other obvious regiment to be linked to. They considered themselves not just the original Light Infantry but a cut above other regiments of the line as well. They were fiercely proud of their reputation for producing senior officers, and had the distinction of earning 10 VC’s[50]. They were the natural choice, as they saw it, to be the new Rifles.

Two prominent sons of the regiment were well placed to influence these decisions: one, a reformer, highly placed in the War Office and one, hugely ambitious, with the ear of the Queen. Not only that, they were intimates and had been part of the same elite circle for years.

The decision taken that the 26th and 90th be married it seems that the obvious course be that, apart from new dress and new drill, there should be as few changes as possible. The 1st Battalion would continue with their original name of Cameronians, proud to continue their long tradition as staunch Lowlanders. The 2nd Battalion would happily take that of the Scottish Rifles, to them a logical promotion for a regiment which long saw itself as a cut above the average. The fact that both halves, 26th and 90th, were both ‘delighted’ at their union reflects that they had almost certainly, either actually or tacitly, come to an accommodation from which both, as well as several more generations of the Regiment, were to benefit.

It goes a long way to explaining why it took until the 1920’s for the two halves of the Regiment – the Cameronians and the Scottish Rifles – to see that they had more in common than they had apart. For much of this period there had been more than mere rivalry between them. Volume III of the History says:

‘Prior to World War I, The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) were not highly organised on a Regimental basis. The two Regular Battalions adopted a somewhat parochial attitude. Members of the 1st Battalion liked to be called ‘Cameronians’, those of the 2nd Battalion ‘Scottish Rifles’. There were minor differences in dress, and long serving personnel – both Officers and men – tended to remain with one Battalion throughout their careers. Transfer from the 1st to the 2nd Battalion, or vice versa, was a matter for regret, if not actual resentment.’[51]

World War I was the catalyst. It took only some strong and enlightened leadership then to finish the job[52].

From the 1920’s and for the next several generations, including of course World War II, the Regiment added to its reputation in many different theatres of war and other operations. The unique character brought about by the 1881 fusion and developed since then was the reason why, come further defence cuts, it was obvious that there could be no question of another amalgamation: disbandment, no matter how regrettable, was the only option. That is why the story ends in 1968.

All regiments consider themselves unique: some are just a little more unique than others.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to many people. Most notably Her Majesty The Queen has graciously given permission for me to quote from and to reproduce papers in the Royal Archive. Mrs Julie Crocker, Assistant Archivist, could not have been more helpful.

I am particularly grateful to Lieutenant Colonel David Murray (late Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders) on two counts. First, he has taken an extraordinarily close interest in The Cameronians since boyhood and has written knowledgeably about them on several occasions. He also read a draft of this article and was generous with his time and knowledge, preventing me from numerous small errors.

The staff of the National Archive, Kew, Surrey were helpful and encouraging and saved me an enormous amount of time.

I am much indebted to Colonel Hugh Mackay OBE and Major Michael Sixsmith who have both read early versions of the text and made knowledgeable and helpful suggestions for its improvement.

Whilst acknowledging all of the above with gratitude all of the opinions expressed are mine and mine alone, as are any errors or omissions.

I would be pleased to hear from any reader who can add to this story or shed light on any other aspects of what has become for me an absorbing story.

Copyright

Copyright © 2007 Philip R Grant

(prgblue@yahoo.com)

All rights reserved.

First published with the 2007 Covenanter. Revised 2020.

The copyright of all of the authors and publishers named is acknowledged. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders. Even where this has not been achieved their contribution is noted with gratitude.

* That equates to at least £1.2m in 2007 based on an index of retail prices.

[i] Quoting Tallyrand

* Wood’s modesty knows few bounds.

· About £¼ million in 2007.

[1] It was here in 1803 that Sir John Moore first started to train permanent light infantry regiments. He is described as ‘The Father of The Rifles’ – see www.army.mod.uk etc. It is one of these curious coincidences that Moore (born in Glasgow) was not only a friend of the 8th Duke of Hamilton (Earl of Angus) but was also for six years MP for Lanark. He was also a close friend of Thomas Graham, later Sir Thomas and later still Lord Lynedoch. Moore died at Corunna at Graham’s feet.

[2] Douglas tartan was not authorised until 1890.

[3] The date is not recorded in the official history. There is no reason to suggest it would have been the same date on which the 26th paraded though it could easily have been.

[4] On formation they had originally worn white / grey trousers but whatever their original colour they were soon battle-worn and usually grey.

[5] There is some evidence that they were always trained as light infantry and so their re-naming was as much as anything a rationisation.

[6] They went on to earn nine more: see The Bravest of the Brave by Philip R Grant published with the 2005 Covenanter.

[7] www.royalgreenjackets.co.uk

[8] Not to be confused with the Light Cavalry Brigade whose charge in 1854 during the Crimean War became a legend.

[9] Edward Cardwell (1813-1886) was Secretary of State for War from1868 to 1874.

[10] The 3rd Lanarkshire Volunteers have the unique record of establishing a football team (1872) which played in the Scottish first division and won the league in 1904 and the Scottish Cup in 1895 and 1905. The club was declared bankrupt in 1967 and disappeared.

[11] By Professor SHF Johnston (Gale & Polden 1957)

[12] General Sir Charles Ellice

[13] Territorial here refers only to geography.

[14] Published in the Dispatch, the journal of the Scottish Military History Society. It is quoted here with the permission of the author.

[15] This is not strictly true. They had shared a depot at Hamilton since 1874.

[16] An extract from The Story of a Soldier’s Life, Constable, London 1903. The origin of the word Grabbie is not known. It may be derived from the name for the crew of an Eastern coasting vessel (a grab or ghurab): a lascar.

[17] National Archives WO33/34/0771 (undated) © Crown Copyright

[18] Note: this should not be read in the same way as the word ‘territorial’ as used at the time of the formation of the Territorial Army in 1908 and up to the present time.

[19] National Archives WO/33/35/815 © Crown Copyright

[20] Note: they are in this order and not in the order mentioned above by Murray.

[21] Here is not the place to explore why Ireland was entitled to Royal Rifles while Scotland was not.

[22] One might say ‘one of his ablest commanders’. Either way, he was at one time nominated to succeed the Iron Duke had he fallen. See Philip Grant’s A Peer Among Princes, The Life of Thomas Graham, Victor of Barrosa, Hero of the Peninsular War, published by Pen and Sword, 2019.

[23] These are held in the Round Tower at Windsor Castle.

[24] Chairman of the War Office committee which took its name from him.

[25] Royal Archives reference RA VIC/E 26/49

[26] Royal Archive reference RA VIC/E 26/63

[27] Royal Archive reference RA VIC/E 26/124

[28] Royal Archive reference RA VIC/E 26/64

[29] All Sir Garnet © Joseph Lehmann (Jonathan Cape 1964)

[30] He also received honorary degrees from both Oxford and Cambridge Universities and was granted the Freedom of the City of London. The scale of this adulation is almost incomprehensible today. Even in Victorian times it was extraordinary.

[31] From Midshipman to Field Marshal (Methuen & Co, London 1906)

[32] This was Major Montresor Rogers VC who later succeeded Wood in command of the 90th and was their last Commanding Officer, and the first of the new 2nd Battalion.

[33] Although the award was not instituted until 1856, earlier outstanding deeds from the Russian and Crimean War were considered as qualifying.

[34] The practice of purchasing commissions was abolished this year and his must have been one of the last.

[35] He studied at the Middle Temple in 1870 and was called to the Bar there in 1874.

[36] It has been said that prior to the formation of the General Staff in 1906 much of its function was carried out by the QMG (Maj Gen EKG Sixsmith in his biography of Haig). Unlike in later years, it was not the case then that QMG’s function was one purely of managing materials and logistics.

[37] Between 1800 and 1904 (when it was abolished) this post was held by only ten officers (if you include Wood): three of them were from the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry. The others were General Sir Rowland Hill (1828-1842) and Field Marshal Sir Garnet Wolseley (1895-1900). Two of the others were royal dukes; another was the Duke of Wellington. Wood thought that the permanent post should be his but it was given instead to Field Marshal Lord Roberts. Wood’s profound deafness may possibly have been just one of the considerations.

[38] The Story of a Soldier’s Life. Constable, London 1903.

[39] It was in this year, 1871, that the C-in-C was persuaded to move his own office to the same building as that of his political master in Pall Mall. The site has now for long been occupied by the Royal Automobile Club.

[40] All Sir Garnet p244.

[41] See Note 36 above.

[42] From Midshipman to Field Marshal (Methuen & CO, London 1906)

[43] Of all of the Ashanti Circle, Wolseley considered Colley the most able.

[44] Ibid p147 et seque.

[45] The Queen asked him to extend his stay but he was mightily discomfited as he had other social engagements to which he was already committed.

[46] Niece of George III and queen of George IV (though excluded from his coronation). She died in 1821 after a colourful (and scandalous) life.

[47] Napoléon IV, Prince Imperial (Full name: Louis Napoléon Eugène John Joseph, 16 March 1856 – 1 June 1879), Prince Imperial, Fils de France, was the only child of Emperor Napoleon III of France and his Empress consort Eugénie. Having been to the RMA Woolwich he begged to be allowed to go on service to South Africa. His family had sought exile in Britain after the disaster of the Franco-Prussian War.

[48] The Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, one of the ‘great twelve’ of the City livery companies, and one of the richest and grandest. Wood was by now a Liveryman of it.

[49] The Queen’s private house on the Isle of Wight.

[50] In his memoirs Wolseley wrote (of the siege of Lucknow): ‘I have seen many a reckless deed done in action, but I never knew a more dare-devil exhibition of pluck than this. In any other regiment this young ensign would have had the Victoria Cross, but to ask for that decoration was not the custom in the 90th Light Infantry’. Had it been, heaven knows how many they might have won!

[51] Page 13.

[52] A notable exception which helped to break the mould was the appointment in 1923 of Lt Col ‘Uncle’ Ferrers and Capt Dickie O’Connor (later Gen Sir Richard) as CO and Adjutant respectively of the 1st Battalion, both having served previously only with the 2nd. (See The Generals by Philip R Grant, published with The Covenanter of 2005.)

Comments: 2