The Cameronian Generals

by Philip R Grant

First Published with the 2005 Covenanter – Regimental Journal of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

[Revised 2007, 2009 and 2021]

“We have to go now, sir: it’s time for us to go.” With these words Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Dow asked for permission to dismiss and to march off parade the 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). But it was a dismissal like no other. It was to be forever.

It was 14 May 1968 and 279 years to the day after their formation, on the same spot in Douglas Dale. The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) were marching off into the pages of history. For an old and proud regiment it was a dire day. The tight-jawed faces of the soldiers said it all. The Cameronians were in the business of obeying orders, no matter how hard or how disagreeable. The order to disband was one of the hardest and most disagreeable that most could imagine. It was also the most unjust.

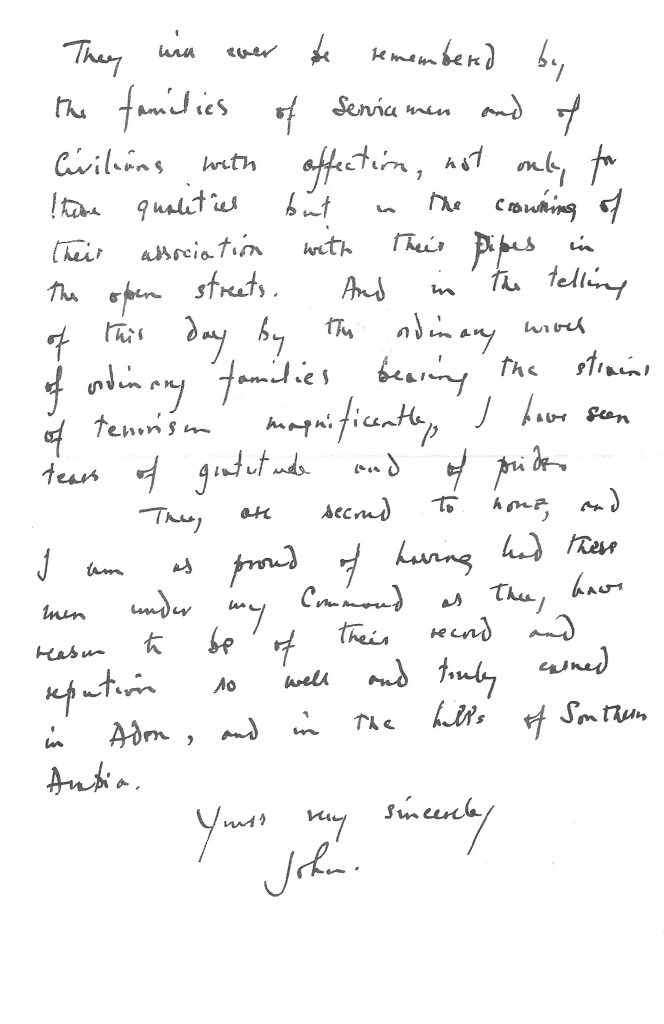

Almost to a man those who paraded that day had been with the 1st Battalion when, only months earlier, they had returned from an outstandingly successful tour on active service in South Arabia. Not for nothing did they march to that stirring pipe tune The Barren Rocks of Aden. There they had borne not just the heat and burden of the day but had taken on the chin an average of one gun or grenade attack every two or three days (102 in nine months)[1]. The day after they left, the GOC Middle East Land Forces, Major General Sir John Willoughby, wrote from his headquarters in Aden to the Chief of the General Staff in London:

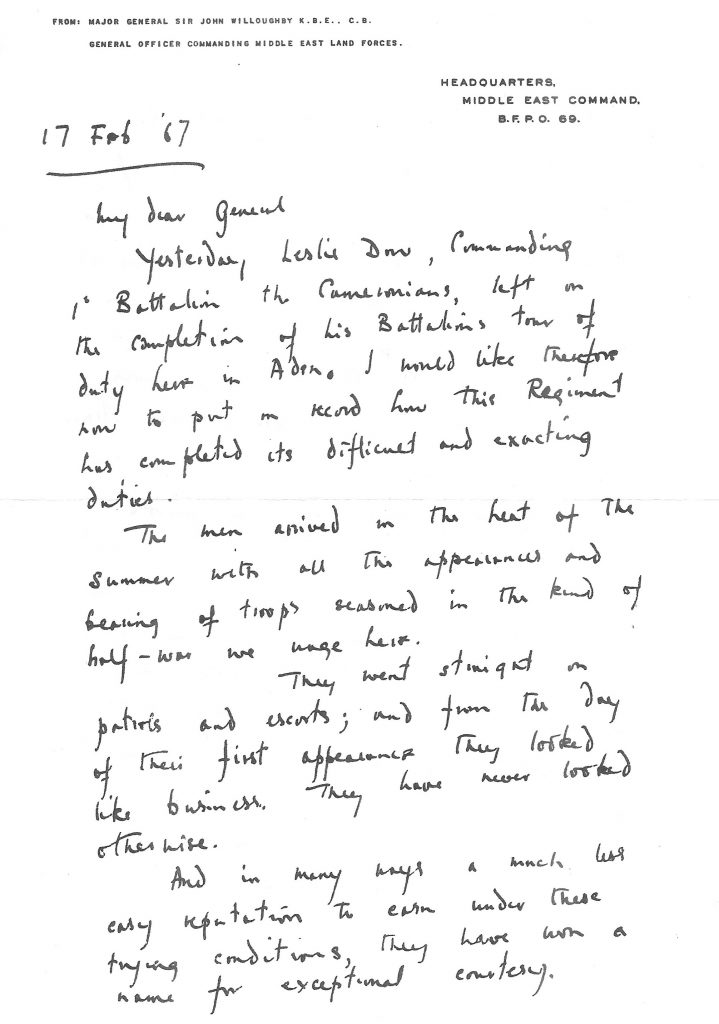

My Dear General,

… The men arrived in the heat of the summer with all the appearances and bearing of troops seasoned in the kind of half-war we wage here.

They went straight on patrols and escorts; and from the day of their first appearance they looked like business. They have never looked otherwise.

And in many ways a much less easy reputation to earn under these trying conditions, they have won a name for exceptional courtesy.

They will ever be remembered by the families of Servicemen and of Civilians with affection, not only for these qualities but in the crowning of their association with their Pipes in the open streets. And in the telling of this day by the ordinary wives of ordinary families bearing the strains of terrorism magnificently, I have seen tears of gratitude and of pride.

They are second to none, and I am as proud of having these men under my Command as they have reason to be of their record and reputation so well and truly earned in Aden, and in the hills of Southern Arabia.

Yours very sincerely,

John[2]

Every member of the Battalion had seen a copy of the letter, and the letter sent subsequently by the Chief of the General Staff, General Sir James Cassels, to the Colonel of the Regiment. In it CGS wrote:

… I saw your Battalion in Aden in January [1967], and everywhere I went there was nothing but praise for the way the men had behaved and acted. …[3]

Of this exchange of letters Volume IV of The History of The Cameronians[4] says: ‘It was unique for letters of this nature to be written about any battalion …’. So why were they marching off into history, to be dispersed amongst almost every branch of the army?

Defence cuts and reorganisations are nothing new. The whole regimental structure which endured both World Wars was based on the Cardwell reforms of the 1870’s and ‘80’s when the primary requirement was to service the needs of Empire. On that basis a regimental system of two battalions per regiment was established. In broad terms one battalion then served at home whilst the other spent anything up to ten years in India or one of the colonies. After World War II the necessary reductions were achieved by disbanding (or placing into ‘suspended animation’) one battalion of each infantry regiment. In the case of the Cameronians the 1st Battalion, which had been decimated time after time in the Far East, was folded into the 2nd which was re-designated the 1st Battalion. Commenting on the ‘new’ 1st Battalion, a senior officer was heard in the corridors of the War Office to the effect that … ‘if anyone wished to see how an infantry battalion should be run he ought to go out to Gibraltar and see the Cameronians[5]. That chimes well with the comments of twenty years later.

In the mid-1950’s still further reductions were sought continuing a process which was still going on fifty years later. In the 1957 round there were some major amalgamations such as the Camerons and Seaforths to form the Queen’s Own Highlanders. (Since then the Gordons too have been culled and their name joined with the Camerons and Seaforths in The Highlanders.) The amalgamation which caused a huge rumpus was the so-called ‘trews versus kilts’ one which, from the Royal Scots Fusiliers and the Highland Light Infantry created the Royal Highland Fusiliers.

In 1966 yet another round of reductions was mooted and the result was announced in parliament on 18 July 1967:

Lowland Brigade. The brigade will reduce by one battalion, which is to be the 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). The Council of [Scottish] Colonels did not recommend an amalgamation with another battalion in the event of reduction.[6]

The original requirement was that the Battalion disband ‘by 1970’ but, as that would have meant mouldering in Scotland for two years with no proper soldierly role, it was decided that nothing was to be gained by simply delaying the awful day. It seemed obvious: 14th May should be the date and Douglas the place.

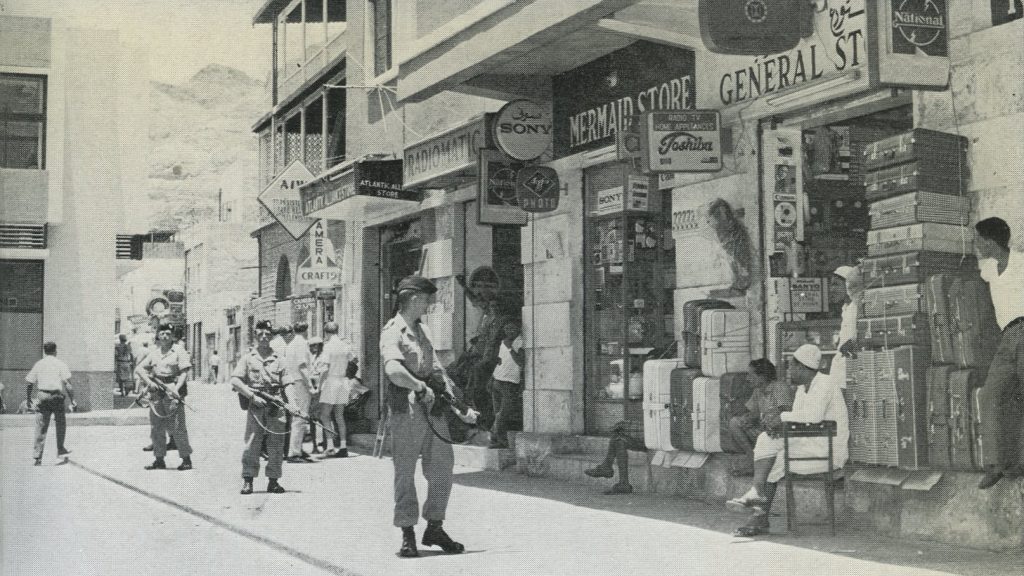

Taking part on the day was a great company of past and present members of the Regiment. Of course it was the 1st Battalion which had pride of place – it was they after all who were disbanding – but there were also many others too. There were the regular officers and men of the 1st Battalion who were ERE (Extra-Regimentally Employed). By far the largest contingent though comprised former members of the Regiment, the ‘Old and Bold’ of all battalions. If the Glengarries on the younger heads of the 1st Battalion were held high, they were held no higher than the heads with grey, white or very little hair of those who proudly took part in the march past. But what distinguished this latter body of men was the group – some say a unique group – which led them. Instead of Glengarries they wore top hats, and morning suits with honours and medals. They were The Generals.

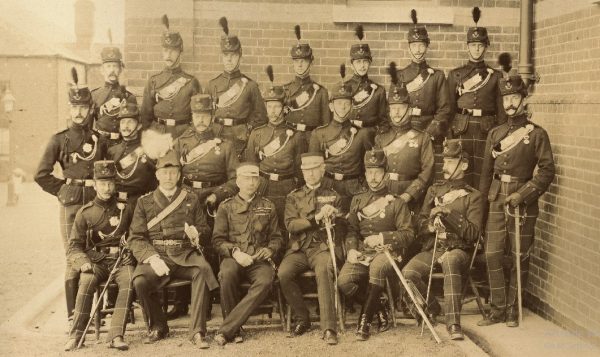

with Lieutenant General Evetts (rear left)

at the 1st Battalion’s disbandment at Douglas, 14 May 1968

South Lanarkshire Council collection

It has long been the view in regimental circles that the number and distinction of these Generals made the Regiment unique. Subject to evidence to the contrary it continues to be the view of the writer, and of others then and now, that it was indeed unheard of that one infantry regiment of just two regular battalions should produce such a rich crop of senior officers.

But what is a ‘Cameronian General’? At first sight an odd question but one which must be addressed. Clearly it would not cover someone who had been transferred for a period to one of the battalions in wartime. The definition used here covers an officer who:

- was commissioned into the Regiment

- transferred to the Regiment

- finished his regimental service with the Regiment

- ensured that his name (and up-to-date address) appeared in the regularly published list of Retired Officers of the Regiment, and, as a catch-all, an officer who

- considered himself to be a Cameronian for any or all of the above reasons.

Brigadier C N Barclay CBE DSO, author of Volume III of the Regimental History, wrote in 1947[7]:

The Author has made a very exhaustive search of records and has come to the conclusion that there is no Infantry Regiment which produced so many high Commanders and Senior Staff Officers in World War II as The Cameronians.

He then goes on to list two Generals, two Lieutenant Generals, five Major Generals and no fewer than nineteen Brigadiers (of whom he, Barclay, was one). While some of them did not survive until 1968 or were unable to travel to the Disbandment, most of them did, and indeed some had been promoted in the interim. Although consideration is being given here only to those alive in 1968, it is clear that the number and distinction of these Generals, the subject of this article, is very much dependent on and a product of Barclay’s 1947 list.

Who were they, what circumstances had brought them to high rank, what had they in common? What contribution had the Regiment made to their success? These are the questions which we will now attempt to answer.

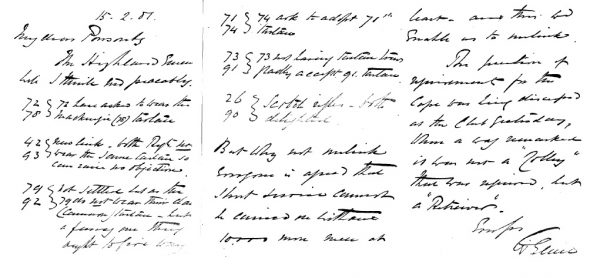

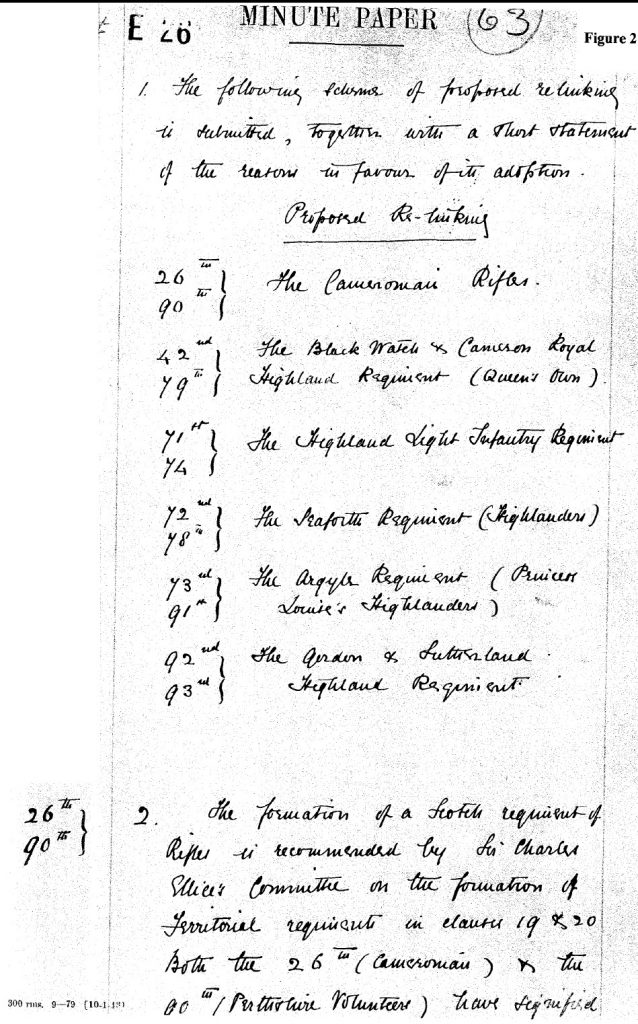

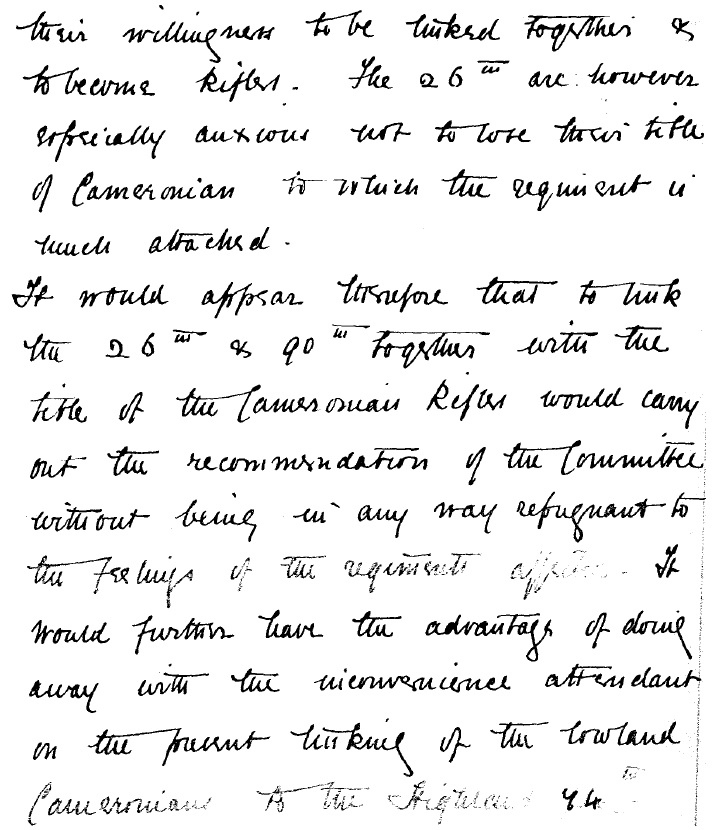

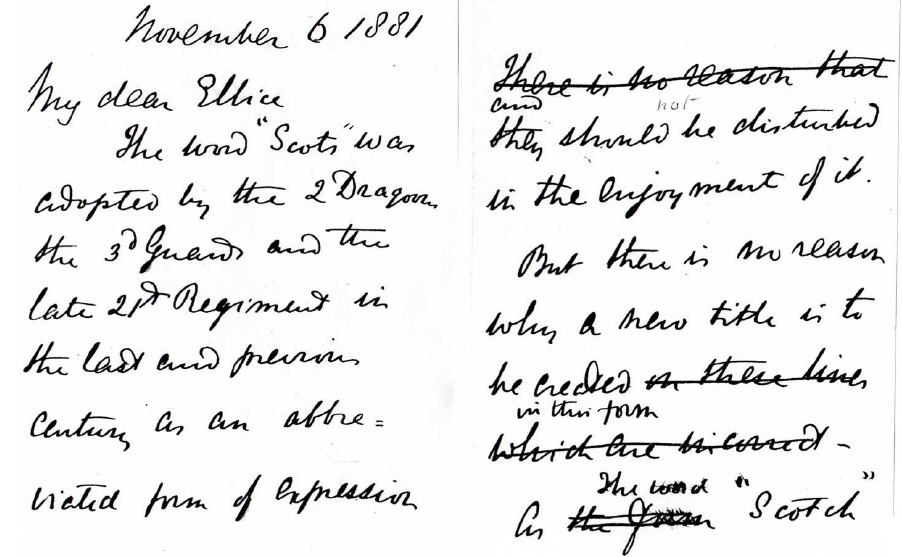

The two regular battalions of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) were formed by the amalgamation in 1881 of two regiments. The 1st Battalion was the old 26th of Foot, The Cameronians. The 2nd Battalion was the old 90th, The Perthshire Light Infantry. At first sight these seemed two very different entities but the amalgamation to form Scotland’s own and unique Rifle Regiment was ultimately most successful. It was the opportunity to take the best of both and to forge something even better. It was the opposite of what was always a hazard in later amalgamations when the component parts reluctantly gave up bits of each in an endeavour to find at least some common ground. It was the unique nature of the Scottish Rifles which meant that, when the time came barely 80 years later for reductions instead of expansion, a dignified disbandment was the only real option.[8] Given the wholesale and radical changes carried through most recently – 2006 – that decision can be seen as not just the right one then, but enlightened.

Historically there was always a tradition of very senior officers being produced by or associated with the Regiment, though in truth, up to 1881, this was based almost entirely on the 90th. They had the distinction of producing no fewer than two Commanders-in-Chief of the army and two Field Marshals – Sir Garnet Wolseley was both. Their founder was himself one of the most distinguished. He was General Sir Thomas Graham of Balgowan, who later became Lord Lynedoch and was the Duke of Wellington’s ablest commander.[9] Others were:

- General Sir Rowland (later Lord) Hill[10], like Graham, ennobled for his leadership in the Peninsular war.

- Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood VC who also became Acting Commander-in-Chief. He was, incidentally, one of seven officers of the 90th who took part in a ceremony of Laying-Up of Colours in Perth in 1872. Of the seven, three wore the Victoria Cross.

Another distinction which the 90th had: three VC’s were to command the Regiment.

Lest it seem that the military virtues were a bit one-sided or that the 90th were marrying a bit beneath themselves, the sheen and shimmer of the 90th should be seen against the deep lustre of the 26th. Not only had they 200 years of distinguished service to the Crown – everywhere from Marlborough’s Blenheim to Napier’s epic campaign in Abyssinia – they had also earned themselves an impressive record in the soldierly skill of rifle shooting. In the Army in India they came 3rd in 1873 and 1st the following year. Back on home service they competed in the Army Championships at Bisley, coming 3rd in 1876 and 1st in ‘77. Indeed the Regimental History (Volume I)[11] goes so far as to suggest: ‘Perhaps its success in marksmanship … was responsible for this decision [to name the new regiment The Scottish Rifles and to make the 26th the 1st Battalion]’. They were also the senior regiment with only one battalion

At a time when the variety and flamboyance of uniforms was unsurpassed it would also add to the impact of large parades: a foil for all that scarlet and gold. Pictures of the celebration of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee confirm this vividly.

It is also worth noting in passing that this expertise in marksmanship was maintained long after the amalgamation. The 1st Battalion (the old 26th) came 1st in the Army Championships again in 1886, and the next year ‘won all of the major championships’ (ibid Volume I). It won the Inter-Regimental Competition in 1890. In 1893 it took both 1st and 2nd prize in the Evelyn Wood Competition at Bisley, and in 1894 Private Brown[12] won the Imperial Prize open to all ranks of the regular army. That the old 26th did so well in a competition named after an outstanding product of the old 90th is a testimony to both halves of the Regiment.

The marriage though ultimately highly successful took some time to gel. In a marriage of strong characters, and especially between those who have enjoyed independence for an extended period, there were bound to be differences. The History records that:

Prior to World War I, The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) were not highly organised on a Regimental basis. The two Regular Battalions adopted a somewhat parochial attitude. Members of the 1st Battalion liked to be called ‘Cameronians’, those of the 2nd Battalion ‘Scottish Rifles’. There were minor differences in dress, and long serving personnel – both Officers and men – tended to remain with one Battalion throughout their careers. Transfer from the 1st to the 2nd Battalion, or vice versa, was a matter for regret, if not actual resentment.[13]

None of that is surprising especially as the concept of amalgamations was a new one and the two halves of the Regiment never served together anyway, indeed the whole structure was designed on the basis that they would not. There is nothing wrong with rivalry, indeed that and competition are often factors which bring out the best in individuals and organisations. But we deal now with a period when these feelings were long in the past.

Although the Colonel of the Regiment rightly headed the 1968 March Past of the ‘Old and Bold’, it is right to list The Generals in their order of seniority. They were:

General Sir Thomas Riddell-Webster

General Sir Richard O’Connor

General Sir Horatius Murray

Lieutenant General Sir John Evetts

Lieutenant General Sir Alexander Galloway

Lieutenant General Sir George Collingwood Colonel of The Regiment

Major General Robin Money

Major General Douglas Graham

Major General Eric Sixsmith

Major General John Frost

Major General Henry Alexander

Additionally we should remember Major General Norris Haugh who was sick and who sent his no doubt heart-felt apologies. There is one other too whom I have kept in the list: General Sir Roy Bucher. He did not join the parade nor is there any record of his having been there. It must be assumed that he was prevented from doing so by infirmity or incapacity.

That is an impressive list but it tells only part of the story. Without counting the Brigadiers (who we will come to later) and except for those who were promoted, here they are:

| 1947 | 1968 | |||||||

| Generals (****) | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Lieutenant Generals (***) | 5 | 3 | ||||||

| Major Generals (**) | 5 | 6 | ||||||

| [24] | [37] |

In trying to make some sort of a comparison, no matter how inadequate a measure it is, I have added on the bottom line [ ] what might be called a star count using the traditional (though originally American) general officers’ insignias as above. Using this crude star count the 1968 measure is more than 50% above what was recorded in 1947. If Barclay thought that the 1947 number was unique then it seems incontrovertible that the 1968 list was equally so, irrespective of the number of Brigadiers.

My reason for including Bucher (though Barclay did not) is simple: he fulfils the criteria above. More than that, and what finally tipped the balance, he is included by General Murray in a memoir he wrote in which he refers to the ‘thirteen generals’[14]. Moreover that is the number quoted by The Times in their obituary of Lieutenant General Evetts. Of course some of the names on the list changed either through promotion or through death.

But now we must confine ourselves to the generals of 1968, most of whom came together on parade almost certainly for the first and for the last time, and to the two who would have given so much to have been there if they could. In trying to establish what brought all of these generals together in one regiment we must start by looking at a necessarily brief summary of their lives.

The following sketchy pen pictures cannot really begin to do justice to their subjects. In two cases there are full, published, biographies to draw on but for the majority other sources have had to be relied on. Regrettably almost all of these sources are secondary. As this gallery of greatness is of interest as much as a collection as for its individual subjects, this is perhaps less serious than if it were an in-depth study of each figure. That said, and considering the inevitably limited size of the canvases, it is hoped that there is enough colour on the writer’s palette to allow them to emerge from the shadows. So, let us now enter the first room marked ‘General’.

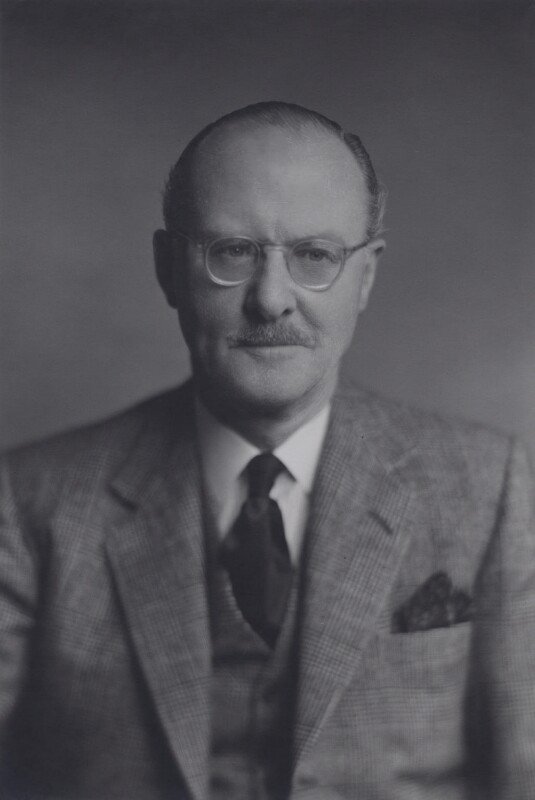

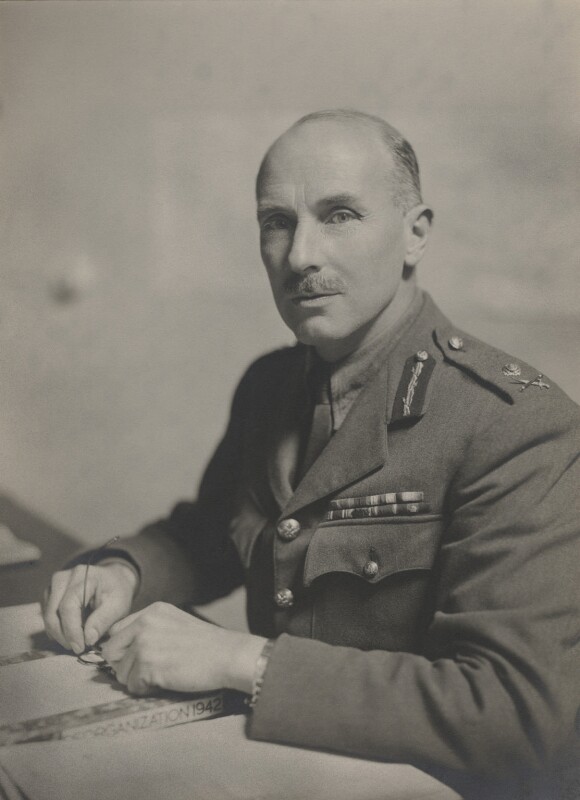

by Walter Stoneman

bromide print, September 1942

NPG x164434

© National Portrait Gallery, London

General Sir Thomas Riddell-Webster GCB DSO DL spent most of World War II at the War Office. He was Quartermaster General 1942-1946. Before that as a Major General he was Director-General Movements and Quartering (1938-1939) and Deputy Quartermaster General (1939-1940). In between these appointments he was Lieutenant General of Administration Middle East (1941-1942) with a brief period in 1941 as GOC-in-C Southern India. So as either Deputy or Quartermaster General he bore huge responsibilities during the pivotal events of Dunkirk, the North African offensive, the invasion of Italy and for D-Day and beyond, not to mention the awesome planning necessary at the end of the war, the occupation of defeated Europe, and the return to peacetime. On his retirement in 1946 his career was capped with his appointment as Colonel of the Regiment 1946-1951.

Riddell-Webster was born in 1886, went to school at Harrow and then to the RMC Sandhurst. He was commissioned into The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1905. Promotion came slowly in those days. By 1914 he was the junior Captain in the Regiment and still a Captain in 1918 though holding the brevet rank of Major. Much of his war was spent as a staff officer in France and in Italy. He was awarded the DSO as well as the French and Belgian Croix de Guerre. It was during the inter-war years that he rose steadily. After Staff College he commanded a company of the 1st Battalion as a Major (Brevet Lt Col) and then in 1930 he took command of the 2nd Battalion. He commanded a brigade in India 1933-1936 and by 1938 he had reached the rank of Major General.

Writing in The Covenanter Brigadier CN Barclay said[15]:

It is usual, although not invariable, for officers who attain high rank to have a penchant for either command or the staff side of soldiering. General Riddell-Webster was not among them: he was at home in either – whether it was commanding a Company, Battalion or Brigade …; or directing the dispersal of troops arriving from Dunkirk or dealing with the vast administrative problems as QMG in a national war. … Any duty requiring organizing ability – running a Weapons or Sports meeting, chairing a led discussion whether as a comparatively junior or senior officer – came easily to him. His bent in this direction greatly helped him at the Staff College (as student and later as a member of the Directing Staff) and later still at the Imperial Defence College.

Barclay then goes on:

He was an enthusiastic sportsman. A fine rider to hounds and a keen contestant in point-to-point races …; a useful golfer and, in his younger days, always ready to try his hand at any other sport or game …. [He was also a fine shot.]

During the time he commanded the 2nd Battalion in Glasgow he hunted regularly and in this connection it is worth mentioning two of his companions. He encouraged his young officers to hunt with him and in this regard reference is to be found to the best horseman the Regiment ever had, Major General Henry Alexander, who was then a subaltern. But another with whom he hunted regularly with the Eglinton was Brigadier General James Jack (of whom more later as well). Bearing in mind that Jack had joined the Regiment ten years before Riddell-Webster this represented almost three ‘generations’ of the officer corps.

Barclay sums up the man – the General:

Although he had very definite opinions on most subjects he was always ready to hear a different view; after hearing it he would state his own case in no uncertain manner, and he was nearly always right.

He died in 1974 aged 88.

***

by Walter Stoneman

bromide print, 1946

NPG x186912

© National Portrait Gallery, London

General Sir Richard O’Connor KT GCB DSO*[16] MC was described in his obituary in The Covenanter[17] as ‘unquestionably the Regiment’s most distinguished soldier of his generation’. His crowning achievement was his defeat of the Italian 14th Army in 1941. Who knows what else he might have achieved had he not then spent the next three years as a prisoner of war.

He was born in 1889. After school at Wellington College he went to RMC Sandhurst and from there he was commissioned into the Regiment, joining the 2nd Battalion in 1909. (For this and for much else which follows we are indebted to his excellent biography, The Forgotten Victor by Lt Col Sir John Baynes.[18]) The following ten years, formative for any young man, were to shape him and his career. His obituary in The Times said (in part)[19]:

O’Connor’s record in the First World War was remarkable. He was mentioned in despatches nine times [it was seven, another two were added in WWII], was awarded the DSO and bar, the Military Cross, and the Italian Silver Medal for bravery …. He was 25 years of age when the war broke out and he was in the thick of the fighting on the Western Front practically without a break. As a company commander and adjutant he became a legend in his own regiment. He was Brigade Major of [two] Brigades; and he created a precedent when he commanded the 2nd/1st Battalion of the Honourable Artillery Company … for it is a three centuries old tradition in the HAC that their units should be commanded by one of their own….

18 years after the end of the First World War, O’Connor was still only a major in his regiment …. After 1936 promotion came to him quickly. He was selected … to command the 1st Battalion … but before he could take up the appointment he was posted … as Commander of the Pershawar Brigade … a coveted command. After two years on active service on the [North West] Frontier, O’Connor was promoted Major General and went to Palestine in command of the 7th Division.

In 1920 he had attended the Staff College (to which he was to return as an instructor) In 1924 he was to transfer to the 1st Battalion, once more in the post as Adjutant, and during a most important era which will be referred to later in detail.

As a young man Baynes says O’Connor was ‘a very keen rider with a reputation for boldness in the hunting field and on the point-to-point course’.

Come 1940 he was in Egypt in the rank of Lieutenant General and given command of a force of some 30,000 troops. With them he destroyed the Italian army in the first Libyan campaign. They ‘advanced 500 miles in eight weeks, taking 130,000 prisoners, 400 tanks and 1,200 guns’ (ibid). It was pure misfortune that he was to be captured in early 1941. He spent the next three years incarcerated in Italy until his second and successful attempt to escape. By June 1944 he was in the field again in command of VIII Corps in Normandy but although he gave the impression to many that he was unaffected by his three years in captivity, there was in some minds a lingering doubt as to whether, as Baynes puts it, ‘he lacked some of his original fire and confidence’. Perhaps he had aged more than others and, at 55, he was in any case ‘old for the wartime command of a corps’ (ibid).

By the end of the year, after a fully successful but perhaps lacklustre period in Europe (when his ‘scope for original action was very limited’ – ibid) he was asked to go to India as GOC-in-C Eastern Army. In a personal letter Montgomery (his old contemporary at Staff College) wrote: ‘You will be a great loss here. But you are needed in India.’ Though it was not an operational command its importance was undoubted and the high esteem in which he was held was underlined by his promotion to the rank of General. With the end of the war his district had ceased to be the most important and he was moved to take over the huge combined Northern and Western Army. By early 1946 Montgomery (who was taking over as CIGS) asked him to return to London to the Army Board, originally in the post of Military Secretary but ultimately to the even more important job of Adjutant General, described to him by his old friend Field Marshal Viscount Wavell as ‘… the most important job in the Army at the present time’. He was joining the Army Board just as Riddell-Webster was leaving it.

Of this period Baynes wrote:

… his personality was not entirely suited to his appointment. Like many great soldiers he was politically unsophisticated, and his simple outlook and shining integrity were often a handicap when fighting his corner amidst the intrigues of Whitehall. While he had enjoyed his three years at the War Office … [as a Major] 1932 to 1935, his return at an exalted rank eleven years later did not bring him the same happiness…[20]

In 1951 he succeeded Riddell-Webster as Colonel of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). In 1964 he was appointed by the Queen to be her Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. In 1971 Her Majesty appointed him one of the sixteen Knights of the Thistle, an honour second only to that of the Garter though its numbers are smaller and so, perhaps, even more select.

Of his character much has been written. The Times:

He had a quiet, retiring, almost shy manner, but could sometimes be alarmingly direct in thought and speech.

When both were elderly and long retired Murray was to write to him: ‘Whether you are prepared to accept it or not, the fact remains that [when you arrived back as Adjutant in 1924] you were a somewhat frightening person. We were all told about the officer of the HAC who had fainted while being dealt with by you.’[21]

The Sunday Times in an article entitled: ‘The Lost Leader’ of the Desert War[22]:

Despite his self-effacing and diffident manner, he had a subtle magnetism. Small[23] and neat as a bird, he was, in the words of a colleague, “always springy and alert, even when still – always vibrant and alive”.

Honoured by Queen and country, revered in military circles, he died in 1981 at the age of 91.

***

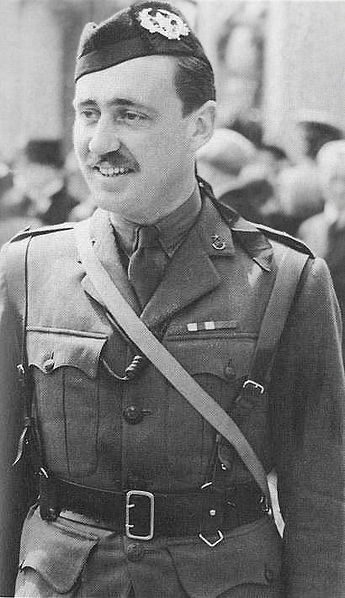

by Bassano Ltd

half-plate film negative, 18 March 1963

NPG x175418

© National Portrait Gallery, London

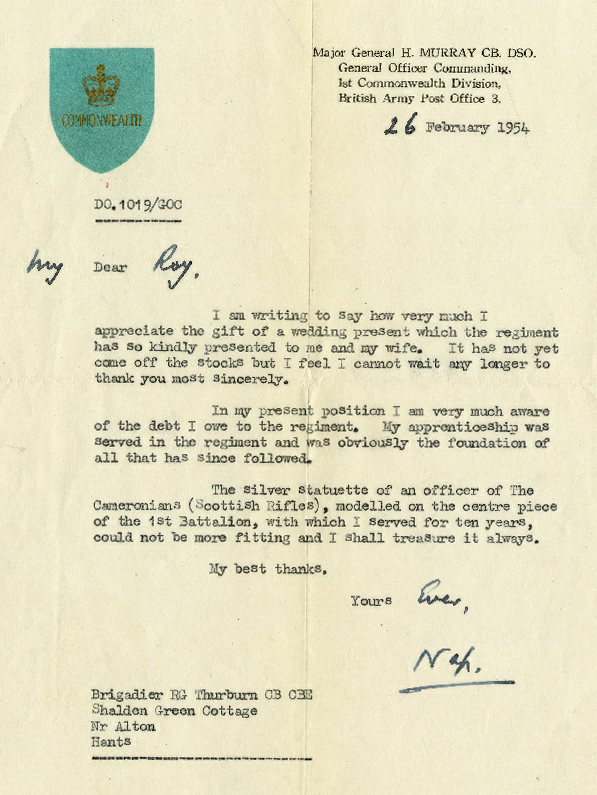

General Sir Horatius Murray GCB KBE DSO was born in 1903, went to Peter Symonds’ School, Winchester, and from there to the RMC Sandhurst. In 1923 he was commissioned into The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) with whom he served almost continuously until going to Staff College in 1936. As mentioned earlier, this was a pivotal time in the Regiment and he had a thorough grounding from officers who had distinguished themselves in World War I. His talents were spotted early. Whilst still a subaltern he was Adjutant of the 1st Battalion and held the post for the unusually long period of three years.

Early on he was nicknamed ‘Nap’ (short for Napoleon) because of his dedication to his profession, which must have been remarkable in a regiment where a high level of professionalism was far from unusual. He was a good soccer player and he represented both the RMC Sandhurst and the Army Crusaders as a formidable goalkeeper.

In 1942 he was selected to command the 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders which he led at the battles of Alam Halfa and El Alamein. Having been wounded at the latter he spent six months in hospital from which he discharged himself, and shortly afterwards was given command of 153 Infantry Brigade (51st Highland Division)[24] which he led in Tunisia and Sicily. He later went on to lead them in the Normandy campaign. Soon he was promoted to take over command of 6th Armoured Division from the then incumbent, the future Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer. As ‘Nap’s’ obituary in the Daily Telegraph said[25]:

It was not unknown for an infantryman to command an armoured division … but Murray’s performance in the gruelling Northern Apennines winter and later in the Po Valley was exceptional by any standards. Not only did he show a grasp of the intricacies of armoured warfare but also paid so much attention to the morale and welfare of the division that it was able to outfight and outlast the resourceful and skilful German troops who confronted it. …

Having qualified as an interpreter he [had] served with a German regiment on an officer-exchange, an experience which proved of great value understanding German military psychology later.

His obituary in The Covenanter adds[26]:

In the decisive action in the Po Valley in 1945 his division broke out of the Argenta Gap and sliced through the German rear echelons, encircling and destroying the bulk of the German forces. Quite a feat!

At the end of the Italian Campaign he accepted the German surrender on the Austrian border and was faced with the distasteful task of repatriating thousands of Russians who had been serving with the German army. He had no alternative but to obey orders but he delayed handing them over to the Red Army long enough to allow many to escape.

At this time he briefly commanded XIII Corps in the rank of Lieutenant General.

At heart he was always an infantryman. After a short spell at the War Office, which he did not enjoy (pace O’Connor), he was successively GOC 1st Division in Palestine, 1948-1949, GOC Northumbrian District, and then, 1953-1954, GOC the Commonwealth Division in Korea. Once more a Lieutenant General, he was from 1955 to 1958 GOC Scotland and Governor of Edinburgh Castle. Promoted again, his final command was in NATO, 1958-1961, as C-in-C Allied Forces, Northern Europe with his headquarters in Oslo. He was Colonel of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) 1958 to 1963.

Of his character the Daily Telegraph said:

Dignified in appearance, Murray appeared somewhat aloof on first acquaintance but had a warm personality and a special ability at getting on with the younger generation; his tolerance of long hair and other foibles of junior officers surprised many but typified his understanding of what was important and what was not.

He wrote a short but important memoir published in The Covenanter in 1972 and entitled A Gaggle of Generals. This will be referred to and quoted at length later.

[The writer was commissioned into the Cameronians during General Murray’s colonelcy.]

He died in 1989 at the age of 86.

***

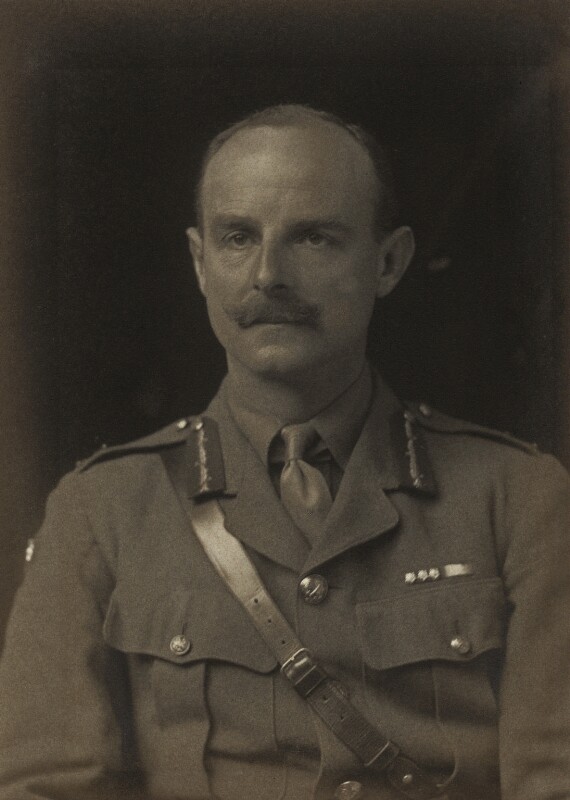

by Walter Stoneman

bromide print, September 1949

NPG x166214

© National Portrait Gallery, London

General Sir Roy Bucher KBE CB MC DL There is a case for including this distinguished officer based on the criteria above, though his service with the Regiment was cut short when he was wounded. He was commissioned into the Regiment in France at the start of World War I and in 1915 was wounded at Givenchy.

He was born in 1895 and educated at Edinburgh Academy. Following his introduction to regimental life and to action in the trenches he was, like so many, a casualty. After that and for much of his life his soldiering was to be in India. He attended Staff College in 1927 where O’Connor was one of the Directing Staff (instructors).

From early on most of his career was spent with the cavalry. Up to the outbreak of World War II he was in command of the 13th / 18th Royal Hussars[27]. He also commanded Sam Browne’s Cavalry. Of them it has been said that, “They were very grand and very picky”. From there he rose steadily filling both command and staff posts. In 1946 he became C-in-C Eastern Command (India) where he succeeded O’Connor. So successful was he that he became the last British Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army a post that would have given him command of numbers far in excess of any but a very few generals in either world war.

Anyone who has had the privilege of serving knows that the early years shape much of an officer’s later career, not to mention his character. No doubt this is why Bucher chose to remain on the list of Retired Officers which was published regularly in The Covenanter. If he considered himself a Cameronian then that surely is sufficient reason to include him with so many of his distinguished contemporaries.

He died in 1980 at the age of 84.

***

by Walter Stoneman

bromide print, 1955

NPG x167458

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Lieutenant General Sir John Evetts CB CBE MC was born in 1891 and after school at Lancing College went to the RMC Sandhurst from where he was gazetted in The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1911. He served most of World War I in France being wounded several times and awarded the MC. He was later to go on to be a highly successful commander, but his greatest contribution was as a staff officer and administrator. The Times said of him[28]:

… he was given command of the 1st Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles in Egypt. What would have been a normal tour in command was interrupted by the outbreak of the Arab rebellion in Palestine where Evetts commanded 16 Infantry Brigade from 1936 to 1939. He proved himself to be a resourceful and inspiring commander of troops and was appointed CBE for his services in 1937, and CB in 1939.

Evetts was serving in India when war broke out in 1939. He commanded Western (Independent) District in 1940 before moving to the Middle East where he was appointed GOC 6th Division. He led his division successfully during the brief campaign in Syria in 1941 but soon thereafter returned home to assume the onerous appointment of ACIGS* [in the rank of Lieutenant General] in the War Office with special responsibility for Weapons Procurement. *Assistant Chief of the Imperial General Staff

This was a vitally important if unglamorous appointment which Evetts discharged to the best of his considerable ability. Indeed much of the credit for equipping the British Army to take part in the Normandy Landings must be his. …The Americans recognised his services by awarding him the Legion of Merit in 1943.

In 1944 he became Senior Military Adviser to the Ministry of Supply and as such was the only military member of its Council, the others being highly qualified scientists. He retired from the Army in 1946. The Times continues:

He then became a senior member of the British team involved in developing and testing nuclear weapons in Australia; he was Head of the Ministry of Supply staff from 1946 to 1951, and Chief Executive of the Joint UK-Australian Long Range Weapons Board of Administration from 1946 to 1949. Evetts was knighted in 1951 and had a successful career in industry from 1951 to 1960.

Evetts [Air] Field on the Woomera Ranges, South Australia, bears his name to this day.

Mention must be made of two written contributions by Evetts. In the early 1920’s, while on the staff of Major General (later General Sir Ivor) Maxse, he co-wrote, with Basil (later Sir Basil) Liddell Hart, the article on Infantry in the 12th Edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica[29]. And while OC the Regimental Depot at Hamilton ten years later wrote a set of Standing Orders for the Regiment of such clarity and concision that although updated from time to time they were never superseded.

Like many of his friends and contemporaries he was a keen sportsman. He was an excellent shot, a good horseman and an enthusiastic polo player, but his principal success was on the cricket field. He turned out for the Free Foresters and Yorkshire Gentlemen. In later life he wrote several letters to the press pointing out how English cricket could be improved.

He died in 1988 at the remarkable age of 97.

***

by Walter Stoneman

bromide print, September 1942

NPG x164368

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Lieutenant General Sir Alexander Galloway KBE CB DSO MC. It would be hard to improve on the obituary of him written by Major General Sixsmith which appeared in The Covenanter[30].

In the death of General Galloway the Regiment has lost one of its most distinguished and best loved officers. He was born in 1895 and on the outbreak of the Great War he was just going up to Cambridge. He immediately volunteered for service and was commissioned and went to Gallipoli with 4th Battalion KOSB. He served there to the end of the campaign, coming away in the last ship of the evacuation. He received his regular commission in the Regiment [Cameronians] in 1917 and was awarded the MC for gallantry in action in 1918. After the war he served with the 1st Battalion and became Adjutant in succession to General O’Connor. He left the battalion … to go to Staff College. He was a student there in 1928 and 1929 and returned as an instructor in 1937 and 1938. He assumed command of the 1st Battalion in 1938 and remained … until … 1940 [when he became] Commandant of the Staff College at Haifa.

It was in the Middle East that he showed his outstanding qualities as a fighting soldier. During O’Connor’s victories in the desert, he was Chief Staff Officer (BGS) to General Wilson [GOC British Troops] in Egypt and he went with him in the same appointment when Wilson commanded the ill-fated expedition to Greece. … As in Gallipoli, Galloway was the last off and there were many who testify to the skill with which he organised the evacuation. When, in November 1941, the Eighth Army was organised to drive Rommel out of North Africa, Galloway was appointed as Cunningham’s Chief Staff Officer. [Cunningham was GOC 8th Army.] At first the battle seemed to be going well but Rommel succeeded in defeating each of the three British armoured brigades in detail. With only 30 tanks in running order Cunningham ordered a withdrawal. Galloway saw that such a move would play right into the hands of Rommel and ensure the destruction of the Eighth Army. Torn between loyalty to his Commander and a knowledge of what the battle demanded, Galloway held back the withdrawal orders and personally informed Auchinleck of the situation.

Auchinleck [C-in-C Middle East Command] accepted Galloway’s assessment and came forward himself to command. The situation was restored and Rommel was driven back to the Tripoli border. Auchinleck realised to the full the part Galloway had played in the battle and he was awarded the DSO and mentioned in despatches.

It is the view of the eminent historian, and author of The Desert Generals, Correlli Barnett, that:

Sandy unquestionably saved Operation Crusader from turning into a disastrous defeat, and I have always believed that Auchinleck made a great mistake in pitching Richie from Cairo into (supposedly temporary) command of 8th Army in the middle of a battle, when Sandy would have been the better choice, both in terms of decisive and energetic leadership and of knowledge of the current state of affairs. He would also have averted the disaster of Gazala in 1942.[31]

Sixsmith’s obituary continues:

Galloway was promoted Major General, for a short time used as Deputy Chief of the General Staff in Cairo and as such sent to the United States to select equipment for the Eighth Army. On the way back he was called to the War Office and told he would immediately take up the appointment of Director of Staff Duties there. He was furious. All his hopes were centred on getting command of a division in the forthcoming renewal of the desert battles. For several days he did duty in the War Office dressed in his tropical khaki drill as if to establish the fact that he did not belong there.

Writing of O’Connor’s time on the staff of the Director of Staff Duties (1932-34) Baynes says: ‘Though smaller than the directorates of Operations and Training, that of Staff Duties might be said to have held the reins of power through its control of appointments [including] … the employment of many of the brightest rising stars.’[32]

And a further point: it is recorded that at this time the Minister and strategic planning committee in the Middle East, anxious to inform their counterparts on the Cabinet committee in London, recommended that if anyone wanted to know about desert warfare they should ask Major General Galloway.[33]

Sixsmith again:

The decision was indeed unfortunate for Galloway. After two years in this most important and gruelling War Office job [it was actually just over one year], he was given command of 1st Armoured Division and he returned full of hope to North Africa in the expectation that he would soon be leading his division in battle in Italy. It was not to be: the division was never in action in his time.

He did get another taste of action at the second battle of Cassino. General Tuker, Commander 4th Indian Division, fell ill and Galloway was hurried in to take temporary command, but he acted on somebody else’s plan in an abortive battle and that added to his frustration. Had he been given command of one of the divisions in the Desert war or had he taken his division into battle, there is no doubt he would have gone to the very top. Montgomery knew his worth and used him as his Chief of Staff … while de Guigand was away, and had him as Commander XXX Corps during the occupation [of Germany]. He went on to the important posts of GOC-in-C Malaya in 1946 and was High Commissioner and C-in-C British Troops in Austria 1947-49 [actually 1948-50 and during a time when his own 1st Battalion were under command], but there is no doubt that he felt, and others certainly knew, that this was all less than could have been.

… Sandy was tall, well-built and athletic. He was an exceptionally good golfer and a great cricketer. When he was a student at the Staff College he made a new record for the number of wickets taken in a season. … Sandy had a fiery temper. … In 1925 a subaltern in the Machine Gun Platoon gave him the nickname ‘PR’ which signified ‘Permanent Rage’. But ‘Nap’, adopting Shakespeare, says, “His temper was like summer lightning and left not a mark behind.” He was of a most generous disposition, he had a great sense of humour and he sparkled with enthusiasm.

He died in 1977 at the age of 82.

crossing Horse Guards Parade, Whitehall, June 1943.

South Lanarkshire Council collection

***

c.1957-1958

South Lanarkshire Council collection

Lieutenant General Sir George Collingwood KBE CB DSO was Colonel of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) at the time of the disbandment of the 1st Battalion. None of his illustrious predecessors can have had a more challenging or heart-wrenching prospect. He was much loved and admired by all in the Regiment. He rejoiced in the nickname by which he was widely known: ‘The Wicked Uncle’.

He was born in 1903 into a distinguished Northumbrian family and numbered the famous Admiral Collingwood (Nelson’s deputy and successor after Trafalgar) amongst his forebears. Indeed he was destined for the navy himself until it was discovered that he was colour blind. He went to RNC Osborne and then to BRNC Dartmouth before transferring to the RMC Sandhurst where he was a contemporary of ‘Nap’ Murray. They were commissioned into the Regiment on the same day in 1923. They succeeded one another as GOC Scotland and later as Colonel of The Regiment.

Collingwood’s early days with the 1st Battalion in India were notable for his sporting contribution. He captained what, for an infantry battalion, was a remarkably successful polo team. His interest in horses continued throughout his life. His crowning success in this field was when he was appointed a Steward of the Jockey Club. For those not familiar with this ancient institution which used to run British racing: it has only 120 members of whom nine serve as Stewards.

There was a pivotal time in his early service. When O’Connor was given command of 7 Division in Palestine he asked Collingwood to go as his ADC. As Baynes puts it: ‘Collingwood was rather old for such a post, and was used more as a personal advisor, friend and staff officer than the more usual role of an ADC’.[34] What better training could a future general possibly have?

While the 1st Battalion was in Malaya, 1951-53, Collingwood commanded a neighbouring brigade. It is thought likely that his nickname stemmed from this period. He always had a twinkle in his eye. There was always some mischief afoot. While commanding his brigade during the Malayan Emergency he asked his divisional commander, Major General Urquhart (veteran of Arnhem), if he might absent himself for four days. Pressed as to why it was so important to him Collingwood eventually explained that he planned to fly to Aintree to watch one of his horses running. Sadly, it did not win. (It should be noted in passing that this epic journey pre-dated travel by jet aircraft.)

Urquhart knew his man well. He was ex-Highland Light Infantry and Collingwood took command of their 10th Battalion in 1942 (at the same time that Murray took command of the 1st Gordons). From 1944 to 1945 he commanded the 33rd Indian Brigade in Burma (while the 1st Cameronians were with the Chindits). He then went back to India to command the 23rd Brigade (1945-46) and on promotion to Major General he commanded 52 Division, 1952-55. Between 1957 and ’58 he commanded the Singapore District before, on further promotion, he took over as GOC Scotland and Governor of Edinburgh Castle. It was thought to be unique then (and perhaps still is) that two officers of the same regiment succeeded one another in these posts. Not only that but he also succeeded Murray as Colonel of The Regiment, which post he filled from1964 to 1968.

When, as Colonel of The Regiment, he visited the 1st Battalion in South Yemen in 1966 it had left Aden for a tour up-country. He reminisced to that generation about how like the country and the operations were to those he had experienced on the North West Frontier 30 years earlier.

He died in 1986 at the age of 83.

***

photographed as Lt-Col, Commanding 1st Cameronians, 1931

South Lanarkshire Council collection

Major General Robin Money CB MC was commissioned into The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) from the RMC Sandhurst in 1909. He played polo in the subalterns’ polo team with James Jack (of whom more later).[35] He went with the 1st Battalion to France in 1914 and served there and in Flanders throughout World War I. When the 2nd Battalion was being re-formed in March 1915 after the carnage of Neuve Chapelle he was sent as the new Adjutant – a vitally important post and one which clearly showed the high regard in which he was held.[36] The previous month he and O’Connor were the first two members of the Regiment to be awarded the newly instituted Military Cross. He was wounded just two months later at the battle of Aubers Ridge.

He commanded the 1st Battalion in Lucknow and it was during his time that the foundations were laid for the run of outstanding sporting successes which followed, especially in the period 1935-38. Having handed over command in 1934 he returned to Lucknow two years later and was Commander Lucknow Brigade 1936-39. At the outbreak of war he was posted to be Commandant of the Senior Officers’ School where he replaced the later Field Marshal Viscount Slim (who went to command an Indian brigade instead).

He commanded the 15th (Scottish) Division 1940-41 and was then a Divisional District Commander in Northumberland and later in South Wales 1942-44 when he retired. He was awarded the CB in 1943.

It was a particular blow to him and his wife when their son, Roy, who had been commissioned in the Regiment from Sandhurst in the summer of 1939, was killed in action with the 2nd Battalion in May 1940 during the retreat to Dunkirk.

Money and O’Connor were contemporaries though the former was slightly the older. They were both commissioned into the Regiment in 1909. When they were both awarded the MC, Money was already an acting Captain. Both were wartime Adjutants of the 2nd Battalion. Money took command of the 1st Battalion in 1931 whilst O’Connor was nominated to take over in 1936, and in that year they were both given command of a brigade. In this regard they were role models for Murray and Collingwood who were to follow a generation later.

Money died in 1985, at the grand age of 97. His unique collection of photographs from the First World War are an important part of the Regimental Archives.

***

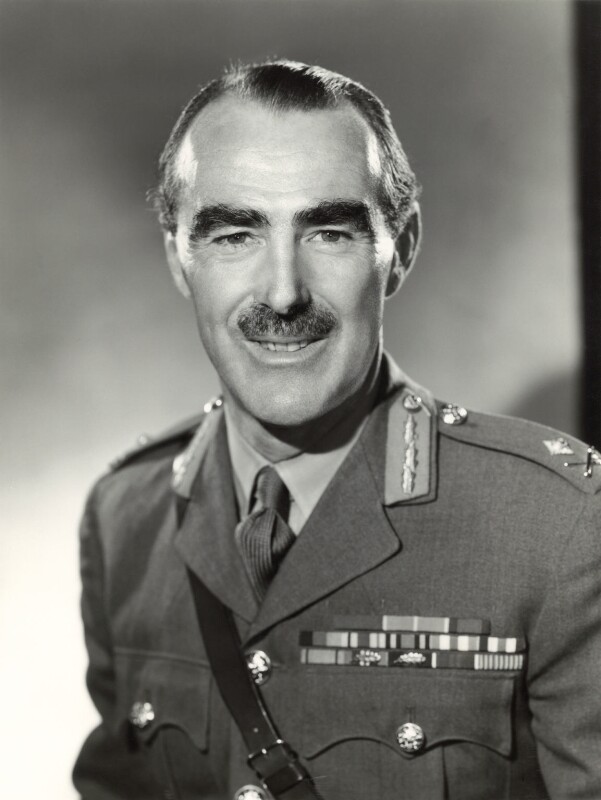

by Walter Stoneman

bromide print, June 1946

NPG x167913

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Major General Douglas Graham CB CBE DSO* MC DL was born in 1893 and was educated at Glasgow Academy. After a year at Glasgow University (where he distinguished himself at rugby) he entered the RMC Sandhurst from where he was commissioned into The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1913. The following year he was with the 1st Battalion when it went to France with the BEF. Within weeks he had taken part in the battle of the Marne but by October 1914 he was seriously wounded. Lying a long way out in no-man’s land he ordered his platoon to withdraw, leaving him behind. Two refused to do so. Corporal Taylor was killed; Private May carried him back about 300 yards under heavy fire and was, as a result, awarded the Victoria Cross. Although left for life with a seriously disabled leg and impaired hearing Graham returned to active duty and in 1916 asked to be posted to the 2nd Battalion in France. He finished the war as Brigade Major of a front-line brigade.

Between the wars he served on the staff, commanded the Regimental Depot in Hamilton and later went on to command the 2nd Battalion. He was in that post at the outbreak of World War II. In between, in 1925, he had returned from India to attend a course at the London School of Economics and Political Science. By early 1940 he was recalled from France to take over command of 27th Infantry Brigade, later renamed 153rd Infantry Brigade.

The new 51st Highland Division, of which the 153rd was part, were sent as reinforcements to the Eighth Army and he was awarded the DSO for his leadership of it at El Alamein. This award was followed only weeks later by a CBE. His obituary in The Covenanter takes up the story[37]:

During the latter stages of the Eighth Army’s long advance across North Africa from Alamein to Tunis, the commander of the 56th Division had been severely wounded and in May 1943 ‘Monty’ had appointed “That gallant old war-horse” to the command of that division in the rank of Major General. Thereafter he led that division during the remainder of the North African Campaign and later, during the landing at Salerno in Italy, where his gallantry had earned him a bar to his DSO.[38]

After injuring his arm and shoulder in the overturning of his jeep … he had been evacuated to UK where, upon his recovery in January 1944, he was given command of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division which he subsequently led in the Normandy Landings in June and throughout the first six months of the fighting in North West Europe. In recognition of the splendid part he played in those operations he was awarded the CB in 1944 as well as the French Legion d’Honneur and another Croix de Guerre.’

He retired from the army in 1947 but returned to uniform when he was appointed in 1954 to succeed O’Connor as Colonel of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). An American officer is said to have once asked the function of this far from purely honorary role, to be told that it was to be the ‘Father of the Regiment’. So great was his paternal interest that he was universally and affectionately known as ‘Daddy’ Graham.

Montgomery coined the nickname ‘The Gallant Old War-horse’. Many knew him as ‘Noisy’ Graham for the gusto with which he was prone to greet acquaintances. (The1915 damage to his hearing was also a contributing factor.) There is no doubt however that he took real pride in his sobriquet, ‘Daddy’. It was the pinnacle of a long and illustrious career.

He died in 1971 in his 80th year.

***

South Lanarkshire Council collection

Major General Norris Haugh received a wartime commission in The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1915 and joined the 7th Battalion in Egypt where it was re-fitting after the withdrawal from Gallipoli. He served with them on operations against the Turks in Sinai and in Palestine. When the 52nd Lowland Division was moved from the Middle East to the Western Front in France he served there until September 1918 when he received serious wounds which ended his war.

In 1919 he applied for and received a regular commission in the Regiment, joining the 2nd Battalion in Colchester in time for them to leave for their tour in India. In 1923 he was with them when they were hurriedly transferred from Quetta to Iraq to take part in a punitive expedition against the unruly Kurds. By this time he had been appointed Adjutant. He continued to serve with the 2nd Battalion in Quetta until the Battalion left in 1927 when he remained behind to attend Staff College. Apart from a short spell with his battalion in 1937 he spent the rest of the inter-war years on the staff. His appointments included that of Brigade Major 6th Infantry Brigade and Grade II (major’s) appointments in Egypt and in UK.

On the outbreak of war he was appointed to command a battalion of [another] regiment. From 1941 to 1942 he commanded 145 Brigade which was based in Devon and later that year he was posted to Northern Ireland as Brigadier General Staff. He then returned to the Middle East in the rank of Major General where he was Deputy Chief of Staff Middle East Command 1943-44. In 1945 he was made Deputy Quartermaster General (under Riddell-Webster).

Like so many he had to revert to his substantive rank and it was as a Brigadier that he went once more to the Middle East, this time as Chief Administrator Cyrenaica. After the end of the British Mandate in Palestine and the withdrawal of British troops his job was subsumed into the headquarters of GOC 1st Infantry Division, none other than Major General Murray. Haugh retired from the army in 1948 after thirty three years service. Of his life and service his obituary in The Covenanter says:[39]

… he retired at the end of a distinguished career in the honorary rank of Major General but, strangely enough, without any of the customary (and in his case, well-merited) decorations to mark his country’s appreciation of his long and valuable service and of the part he played in two World Wars. This has never ceased to be a source of deep mystification and profound regret to all his many friends who have felt that he had been the victim of sheer mischance, and of some mistake that ought long ago to have been corrected. After all there can have been few (if any) other officers who, having risen from the rank of Major to Major General in the late war, had not received some award …’

Ill health prevented his attendance at the Disbandment Conventicle.

He died in 1969 at the age of 75.

***

photographed as Lieutenant and Adjutant,

1st Cameronians, India 1934

South Lanarkshire Council collection

Major General Eric Sixsmith CB CBE was born in 1904, went to school at Harrow and then to the RMC Sandhurst. From there he was commissioned in The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1924. He served with them in China and Egypt and later in India. He was Adjutant of the 1st Battalion 1933-35 after which he went to Staff College. Still a subaltern he was one of the youngest students. There he benefited from the teaching of the future Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery. Two staff postings followed and he was Brigade Major, 2 Infantry Brigade, at the outbreak of World War II.

Thereafter his service alternated between command and the staff. He was GSO 1 of 51st Highland Division from where he went to command the 10th Cameronians. Recalled to the War Office for a year he was then appointed to command the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers in Algiers. He was wounded at Anzio but returned to active service in May 1944 to assume command of the 2nd Cameronians, but his tenure was short. He was appointed Deputy Director of Staff Duties in the War Office in the rank of Brigadier.

He remained there until 1946 when he was sent to India to command 13 Independent Brigade Group. Two years later he was back at the War Office as Deputy Director of Personnel Management. A year at the Imperial Defence College followed that and from there he was posted to Hong Kong as Chief of Staff. Thence he was sent to the equivalent position at HQ Far East Land Forces in Singapore with the rank of Major General.

In 1954 he returned to UK for his last command which was of South West District and 43 (Wessex) Infantry Division. Following this he became Director of Organisation and Training at SHAPE in Paris and retired in 1961.

Of him a friend and contemporary said:

One of the first characteristics I remember was that he was a very Spartan officer. Quetta [where they were at Staff College together] can be very cold, but no one ever saw him huddled in a greatcoat, and he was reputed to sleep cheerfully in the open under one blanket. [He was also seen late on in life, working in his garden in the snowy conditions of a February day, clad in his army issue tropical shorts.]

… He was a man of the greatest integrity. He did what he believed to be right at whatever cost, and his principles were always stated clearly and could rarely be shaken in argument. …

But the adjective I would apply to him above all others was ‘incisive’. His was no hurried judgement. A question … would provoke a pause for thought, and then his answer, clear and forceful, would leave no-one in doubt on his opinion. [This, word for word, could be Barclay’s description of Riddell-Webster – see above.] In spite of this I imagine he was more valuable as a staff officer than as a commander, and that is proved by his series of senior staff appointments during and after the war. I cannot imagine a better Chief of Staff, meticulous in gathering the relevant information, and presenting the situation to his commander with unprejudiced clarity. He was an officer who inspired confidence in his opinions which one knew had never been formed lightly.’

In retirement he started a new career as a writer and historian. Between 1970 and 1976 he wrote a series of widely acclaimed books. Of these his British Generalship in the Twentieth Century became something of a classic, and required reading for any aspiring staff officer.[40] He also lectured on military history at Southampton University and at the Staff College, Camberley.

He had many other interests as well. He was at one time a keen piper, he won prizes for fencing at RMC Sandhurst, and several point-to-point races in India. He was a knowledgeable and avid gardener, he enjoyed classical music and he was a committed Christian who gave of his significant gifts both to his local parish and beyond.

He was appointed CBE in 1946 and CB in 1951. He died in 1986 at the age of 81.

The pipers are from 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

South Lanarkshire Council collection

***

by Walter Bird

bromide print, 23 January 1967

NPG x167694

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Major General John Frost CB DSO* MC. His obituary in The Times began:[41]

‘Johnnie’ Frost carved his name in the annals of Anglo-American military history by reaching and holding the bridge at Arnhem until his ammunition ran out in September 1944, although surrounded by SS Panzers. His name was later illuminated by Conelius Ryan’s book and the Richard Attenburgh film, A Bridge Too Far in which he was portrayed by Anthony Hopkins. He was a founder member of ‘2 Para’, and his indomitable leadership as adjutant, company commander and then commanding officer, established its fighting traditions …

He was born in 1912 and educated at Wellington College and Monkton Combe. He was commissioned into The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) from RMC Sandhurst in 1932. After early service with the 2nd Battalion (under Riddell-Webster, with whom he no doubt hunted) he later went on secondment to the Iraq Levies with whom he served until 1941.

Having volunteered for Special Forces in 1941 he was posted to the new 2nd Battalion the Parachute Regiment. He then took part in many operations but three were to earn him fame as an inspired and inspiring leader. The Times takes up the story:

Frost’s first task … was to lead the raid on the German radar station at Bruneval on the French coast … on the night of 27/28 February 1942. British scientists needed the cacinotron from the heart of one of the latest German radars in order to devise counter-measures. Frost’s C Company was to drop on Bruneval and protect the radar specialist … team while they dismantled the radar and carried it back to a waiting Royal Naval craft.

The Bruneval raid was one of the few entirely successful Second World War parachute operations, thanks to Frost’s meticulous planning, training and inspiring leadership. His hunting horn [a gift on his departure from Iraq] was heard for the first time in battle, as the Bruneval garrison was over-run and captured or killed while the radar was being dismantled. His force escaped in the nick of time … as German tanks reached the cliffs above the beach. The Military Cross was his reward.

Writing in The Covenanter[42], Max Arthur said:

It was a short, sharp, highly successful operation for which C Company received a hero’s welcome in the Solent with Spitfires dipping their wings overhead and naval vessels playing Rule Britannia. The raid had been carried out when the country’s fortunes had been at a low ebb. … Frost was called to Downing Street to relate his experiences to a delighted Churchill.

In November of that year his battalion sailed to take part in the Allied invasion of French North Africa. His commanding officer succumbed to illness and Frost assumed command of 2 Para. Their first operation was nearly a disaster as they had to fight back to their own lines over 30 miles away from where they were dropped. In the subsequent fighting in Tunisia the Battalion repelled three successive attacks by German paratroopers, the third time only after a desperate struggle. The Times again:

In the fighting to re-take Sedjennane, Frost, sounding his hunting horn, led the decisive bayonet charge which obliterated the remnants of the Witzig Group. He received his first DSO for his battalion’s part in the Tunisian Campaign.

After more fighting in Sicily and Italy in 1943 the 1st Airborne Division was withdrawn to prepare for use in France and Belgium during the summer of 1944, but nothing came of the many plans until the Arnhem operation which began on September 17. The Times:

Frost’s 2nd Parachute Battalion was given the task of advancing as rapidly as possible along the north bank of the Lower Rhine to capture and hold the railway and road bridges in Arnhem some eight miles away from the dropping zone. There were said to be only lightly armed … units in the area. So confident was Frost of success that he ordered his batman to load his golf clubs and shot gun in his follow-up baggage.

… little went right: the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions were refitting in the area and, although taken by surprise, were soon opposing the British advance into Arnhem. Opposition grew in intensity and the Germans succeeded in blowing the railway bridge just as Frost’s men were approaching it. It then took until dusk for the battalion to fight its way to the northern end of the road bridge, but all attempts to cross it are driven back. For the next three nights and two days Frost held the buildings around the north end of the bridge against a succession of determined German tanks and infantry attacks while the rest of the division tried to reach him. During the third night he was badly wounded by a mortar bomb. Soon afterwards the Germans managed to set on fire the upper floors of the building in the cellar of which the severely wounded were being sheltered. Fearing that they would be engulfed in flames, he finally agreed to surrender. The Bar to his DSO recognised this and his men’s stoical endurance; and the Dutch later named the re-built bridge after him.

Frost’s post-war career was unexceptional. He attended Staff College and the Senior Officers School. He commanded the Support Weapons Wing at Netheravon (1955-57), the 44th Parachute Brigade TA (1958-61), Lowland Divisional District (1961-64) and finally he was GOC British Troops Malta and Libya (1964-66). There his relations with the Diplomatic Corps were not as smooth as might have been hoped and, instead of any further employment or promotion, he retired in 1967. Of his character The Times said:

… he had deep reserves of courage and willpower. He inspired his officers and men, who had implicit faith in his personal integrity and confidence in his military judgement. He was surprisingly modest and discrete for a man with his strength of character; indeed he was quite shy.

In common with most of his contemporaries he made the most of his sporting opportunities. He boxed, enjoyed fishing and shooting as well as golf. It was the hunt in Iraq which had presented him with his famous hunting horn and he played polo, taking it up again with enthusiasm in Netheravon and in Malta. In retirement he became a successful farmer.

He died in 1993 in his 80th year, the last of The Generals to survive.

***

by Walter Bird

bromide print, 7 June 1962

NPG x163478

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Major General Henry Alexander CB CBE DSO. Yet again we are indebted to the obituarists of The Times. Their assessment was published in full in The Covenanter[43]:

[Alexander] was an able officer of positive character, with a quick brain, an original turn of mind and a pungent tongue. Never afraid to take a decision or to proclaim what he thought, his forthrightness more than once led to a clash with higher authority. It was almost certainly this trait which prevented him from reaching higher rank in his chosen profession.

… Educated at Sedbergh and Sandhurst he was gazetted to The Cameronians in 1931, returning to Sandhurst as an instructor a year before the war. Small, slim and always fit, he made his mark both on the polo field and as a gentleman rider. His war service was unusually varied and he held every campaign medal except that of the Pacific. He commanded the 2nd Battalion of his regiment in Italy and was a full colonel on the operations staff of General Wingate during the second Chindit Expedition into Burma in 1944. In 1946 he became Chief Instructor at the newly established School of Combined Operations; he was later an instructor at Camberley [Staff College] and a student at the Imperial Defence College. [He also commanded the 1st Battalion, 1953-55, and a Brigade during the Malayan Emergency, for which he was awarded the DSO in 1957.]

In 1959 he was offered and accepted the appointment of Chief of Defence Staff in Ghana. Arriving there early in 1960, he quickly got onto good terms with President Nkrumah and addressed himself to the difficult task of building up an army, navy and air force in a political atmosphere from which corruption was not absent.

In July of that year, trouble broke out in the Congo, the United Nations were called upon to intervene, and the Ghana contingent under Alexander was among the first to arrive. … Alexander found himself the senior non-Congolese on the spot. … With the approval of the UN representative, and at considerable personal risk, Alexander succeeded in persuading mutinous Congolese soldiers to lay down their arms, and generally imposed his strong personality on a chaotic situation. …

For some time he continued to receive the backing of Nkrumah, with whose full approval he visited the UN in New York to acquaint them at first hand with the problems of the Congo. This visit did not endear him to certain British circles, and within Ghana pressure was being brought to bear on Nkrumah to rid himself of the British element in the armed forces. … Alexander was summoned to Nkrumah’s office and handed a letter of dismissal, to take effect immediately.

…Alexander produced a readable and surprisingly tolerant account of his service under Nkrumah.[44] At the time, however, he had been less tolerant, both in statements to the press and on television, in his strictures on some British political decisions; and his generally expected appointment as GOC Scotland [where he would probably have succeeded Collingwood] did not materialise. After three years as Chief of Staff Northern Command he retired and went into industry.

In the same issue of The Covenanter there appeared an appreciation by Lieutenant Colonel Duncan Carter-Campbell OBE.

I first met Henry in the summer of 1931 … and remember him as a small, dark and very dapper young man. We soon discovered we were going to join the same Regiment – The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He told me at the time that he had heard from several sources that this regiment took soldiering very seriously – that this was the regiment to join if you wanted to get on. Henry was a most attractive and colourful character and very amusing. …

He was already an accomplished rider on joining the Army and received great encouragement from the Commanding Officer, Lt Col Tom Riddell-Webster, who always took as many subalterns as possible out hunting. …

Posted to the 1st Battalion in Lucknow in 1932 he immediately got down to learning the art of polo. … At the same time he was a hard-working and enthusiastic regimental officer. He was Signal Officer and became Adjutant in 1938 [while still a subaltern and after only seven years of service]. Even in these early days of his career, it was clear that he would rise to high rank in the Army. He was perhaps a hard taskmaster, but recognised by all as a great teacher, post-war, of the new blood.

An earlier appreciation gave space to much more of his sporting prowess.[45] He was undoubtedly the best rider which the Regiment produced. He went to London in 1937 (from Lucknow) to play as a guest in a polo team ‘which swept the board’. In 1938 the 1st Battalion team won the All-India Infantry Cup (as well as many others). In 1939 he was invited to join the team of the Maharajah of Jaipur which toured America. One of the other players was Lord Louis Mountbatten. It is therefore of little surprise that he was later to join the Combined Operations Staff which was commanded by Mountbatten. But his greatest feat as a horseman was to win the Foxhunter Chase in 1951. It was run over the Grand National course at Aintree (lasting ‘only’ 1¼ circuits as opposed to two). In the race he rode Pampeene II which he also owned and trained. For an infantry officer this was (and probably still is) a unique achievement.

His name made the headlines once more in 1968 during the Biafran War when a journalist, a certain Jonathan Aitken – later a Defence Minister in the Major government – was alleged to have broken the unwritten rules of clubland by disclosing a confidence offered to him by Alexander. The result (after a court case which did not involve Alexander) was the setting up of the Franks Committee on the workings of the Official Secrets Act. The Times said: ‘… it was an unhappy postscript to a distinguished and eventful career.’

It would be wrong however to close on a negative note. Alexander had not yet made his final contribution. At the beginning of 1969 he succeeded Collingwood as the Colonel of The Regiment. It was a difficult time. The 1st Battalion had just been disbanded. There remained a disparate collection of territorial and cadet units as well as a Regimental Headquarters and a Museum. Alexander is remembered with great affection for his industry, commitment and devotion to his old Regiment. After nearly six years (in a post which was down-graded to Representative Colonel) he handed over to Brigadier David Riddell-Webster OBE, son of his first Commanding Officer.[46]

He died in 1977 at the comparatively early age of 65.

***

So what are we to conclude? What, if anything, did The Generals have in common? Was it shared background or was it experience? In other words was it nature or nurture? Was this extraordinary crop simply a matter of chance? That cannot be wholly discounted but, as we shall see, it seems likely one can draw a different conclusion. Even if we put it all down to coincidence it does not alter the facts or the outcome. Murray in an important memoir coined the phrase A Gaggle of Generals.[47] With some trepidation the writer would suggest that, although attractively alliterative, the phrase does not really do justice to them. Perhaps Murray was just being modest. Although one associates a gaggle with a group which is upright and alert, there was certainly never any quacking or waddling. Henceforth they will be referred to as a pride, as in lions, for lions they were.

Perhaps one should start by examining what they all had in common. The most obvious is simply the fact that they were all the product of the same small nucleus. Having joined the same regiment they were then to live together, to eat together, to take part in sports together, to compete and to cooperate in every aspect of life. Most importantly they were bonded in their primary aim: to make their battalions the best fighting units in the army. There were elements of cooperation and many of competition, not least at that time between the two battalions. For those not fortunate enough to have enjoyed life in a regiment one must explain: it was far more than a job. It was a way of life. It was at a time when, with few of the distractions of life today, they were to become as close-knit as any other family and a great deal more so than many families today.

Without doubt and without exception all of the generals succeeded because they had outstanding abilities. All were professional soldiers who had risen to the challenges of service through at least one and, in more than half the cases, both World Wars. They had the character, the temperament, the will, the drive, the resolution to persevere through difficulties unimaginable to most people. They also had good fortune. First they were fortunate enough that in spite of the wounds that several suffered, they all survived. Secondly they were fortunate to be in the right place at the right time, or, to put it another way, not to be in the wrong place at the wrong time – though O’Connor is the outstanding example of how to be in both (at different times). Napoleon’s dictum about luck and generals has always held good.

It is an extraordinary feature of the group that so many not just survived but lived to advanced old age. The reader will have been struck already with their longevity. What is even more remarkable is that the older they were the older they got. To explain: the eight who fought in World War I reached, on average, more than 86 years. Adding in the other five, the average age of all of them together comes down to 83, still higher than the average life expectancy of a male born in Britain today (2005). It is hugely greater than the expectancy of someone like Riddell-Webster, O’Connor or Money who were all born in the 1880’s. Perhaps the experience of fighting through and surviving the Great War gave them an extra appreciation of life and a steely grip on it. More likely it was a facet of their characters which helped: that awareness, that keenness, that alertness, enthusiasm and vigour which comes through so often. This at least was something they all had in common.

What was it then which in the first place drew them all together? What elements of their background did they have in common? True enough they all chose to join the same regiment but that was for different reasons. In the case of the later ones, Alexander certainly and probably Frost too, it is clear that the word was out: it was the regiment to join if you wanted to get on. The generation before that, Murray and Collingwood, joined when Captain (later Brigadier) AC Stanley Clarke was an instructor at Sandhurst. On the other hand we are told that O’Connor was delighted to join, though disappointed that there was no vacancy in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders where his cousin was serving already.[48] In earlier days it was no doubt as much to do with vacancies as with any particularly long family or other tradition.

The regiment they joined has been well described by Colonel HH (Harry) Story MC, author of Volume II of the Regimental History.[49] He wrote (in 1961):

Fifty years ago, social conditions, so utterly different from those of today, were reflected, naturally, in the Army. Regular officers were drawn from traditional Army families, from the landed gentry and from the Church and legal profession. For the most part they entered the Army for life. A few were well off, but most of them had to depend on a small allowance from home for the early years of their service. Pay was low. On first joining, a 2nd Lieutenant received 5s 3d a day [26 pence then, and about £18 in 2005]. He was required to pay for his food, to provide and maintain Service Dress Uniform, Full Dress, Patrol Dress, Mess Dress, civilian clothing [including formal morning and evening dress] and furniture for his quarters. … Great emphasis was placed upon physical toughness. Officers were expected to be good horsemen and to follow all field sports.

Baynes sets the scene for 1909 when O’Connor joined:

Although not a rich regiment, as they went in Edwardian days, it was necessary to have a private income of £ 100 a year at the very least, [roughly equivalent to £ 7,000 in 2005[50]] and preferably twice that amount, to serve in the Scottish Rifles. … nearly all officers shared similar interests and backgrounds and had been educated at the major public schools, so they did the same things, but in various degrees of style, and at different levels of expense.[51]