Remember Gallipoli

Sunday 28th June 2015 marks the 100th anniversary of one of the blackest days in the history of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). It was on that fateful day in 1915 that both the 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles attacked the Turkish trenches at Gully Ravine on the Gallipoli peninsula. The combined losses of the two battalions for that single day would never be equaled by the Regiment on any other day of the entire First World War. With this in mind it is rather unfortunate that the significance of the Gallipoli campaign has been largely forgotten, particularly in Scotland.

Both the 7th and 8th Battalions were Territorial Force battalions of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). Both battalions were based in Glasgow; the 7th Scottish Rifles had its headquarters at the old 3rd Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteer drill hall on the corner of Copelaw Street and Victoria Road (the building remains to this day), while the 8th Scottish Rifles were based out of the drill hall on Cathedral Street, now part of the grounds of the University of Strathclyde. Most of the officers and soldiers of these battalions were Glasgow-men, living and working in the city and the surrounding area. As Territorial soldiers they would regularly meet at headquarters for drill, and attend yearly camps where they would take part in field training and musketry practise.

Men of the 7th Scottish Rifles at a pre-war Camp

The Territorial Force wasn’t ever intended to be used as part of an Expeditionary Force abroad; in the event of a large war these soldiers were to be used for home defence, freeing up regular battalions to take the fight to the enemy. By the end of 1914 the situation had changed and several Territorial battalions (including the 5th Scottish Rifles) were already fighting on the Western Front. So it was that the 52nd Lowland Division (comprised entirely of Scottish Territorial soldiers) found itself en route to Gallipoli towards the end of May 1915.

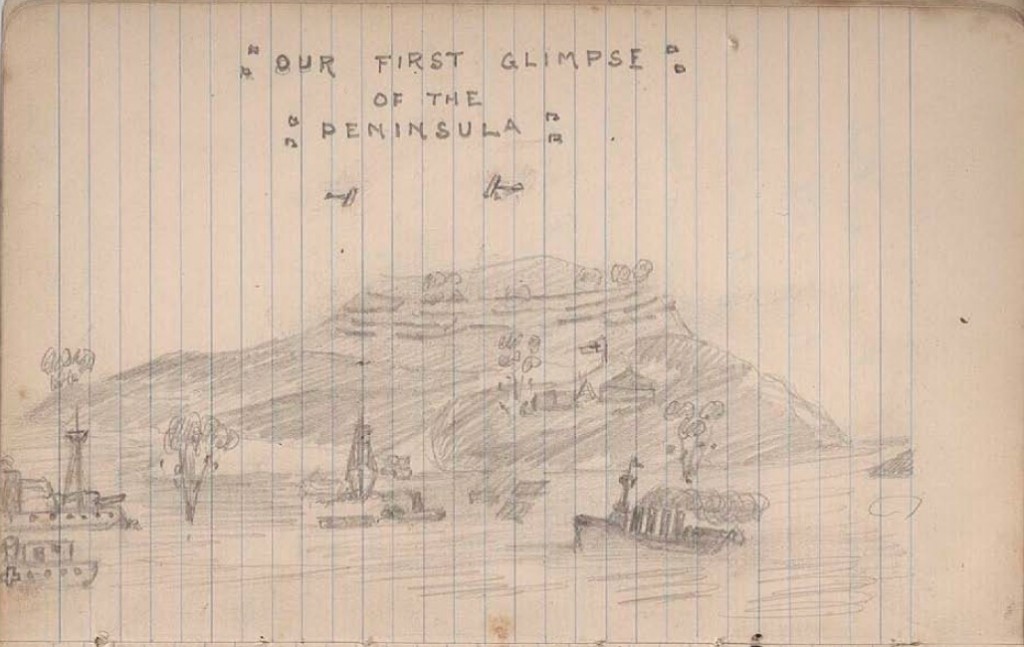

‘Our First Glimpse of the Peninsula’ by Private C. R. Bow, 7th Scottish Rifles

The 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles formed part of the 156th Brigade of the 52nd Lowland Division; both battalions landing at Cape Helles, Gallipoli, on 14th June 1915. The very next day they suffered their first casualties as a result of shelling from Turkish heavy guns, and from sniper and rifle fire. On 21st June the 8th Battalion suffered a heavy blow when their Commanding Officer, Colonel H. M. Hannan, was killed by a sniper.

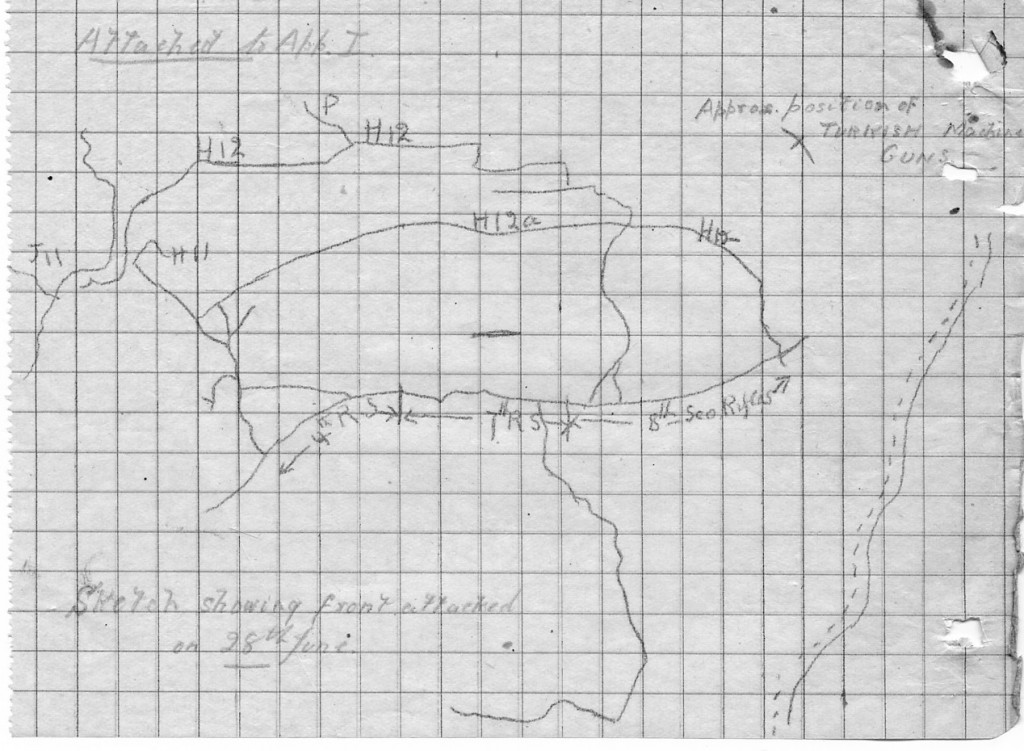

On 27th June, orders were received for a large scale attack the next day. The 156th Brigade would form the right-flank of the attacking force; the 8th Scottish Rifles were to be one of the battalions in the initial assault, with the 7th Scottish Rifles close behind as Brigade reserve. The attack was to be preceeded by a short artillery bombardment of the Turkish defences. Unfortunately for the men of the Scottish Rifles, and unbeknown to them at the time, there would be no bombardment of the trenches they were tasked to capture.

Sketch map showing the area attacked by 156th Brigade on 28th June.

Major J. M. Findlay, who had taken command of the 8th Battalion on the death of Colonel Hannan, described the attack:

Prompt at 1100 the whistles blew, and up and over went Nos. 1 and 3 Companies, followed almost immediately by No.2 Company. Five minutes after they had started they were practically wiped out, and No. 4 Company from the support trench had also suffered severely even before they reached our front trench…there was a ridge running between our line and the Turks’ front line, having crossed which every advancing man was subjected to a deadly fire from right, front, and left, and it was when each successive wave advancing topped this rise that line after line was enfiladed and mown down. Very few men reached the Turkish trenches, and those who did were either killed or wounded, with the exception of one or two men who managed to crawl back to our trenches during the night.

Many of the casualties suffered that day were caused by a Turkish machine gun, sited on the extreme right of the 156th Brigade’s advance. The lack of artillery support on this side of the attack was telling; had the machine gun been knocked out before the men advanced they might well have taken the Turkish trench and with lighter casualties.

Shortly after the 8th Battalion’s attack was stalled by the heavy fire laid down by the Turkish defenders, Major Findlay led a support group to try and gather up survivors and lead them on. This group made it to within around 50 yards of the Turkish trench when Findlay was also hit, shot through the neck. Amazingly, Findlay survived. Captain Bramwell, the adjutant, was not so lucky – he was killed by Findlay’s side – nor was 23 year-old Lieutenant Stout, the signalling officer, who was killed by a shell splinter as he tried to drag Major Findlay to safety.

Major Findlay, Colonel Hannan, Captain Bramwell

Lieutenant Stout

There was no shortage of bravery that day. When it was discovered that one of the few surviving officers of the 8th Scottish Rifles, Lieutenant Tillie, was lying wounded out towards the Turkish lines, Sergeant Miller risked his own life to save him. He succeeded in bringing the wounded officer back to the British trenches. Sergeant Miller never received any gallantry medals for his actions that day, but after the War Lieutenant Tillie did present him with a handsome pocket watch as thanks for saving his life that day.

The 7th Scottish Rifles, who were in reserve when the attack started, were soon sent forward to reinforce the assulting force. They too were caught up in the heavy rifle and machine gun fire laid down by the Turkish defenders. While their casualties were not quite so high as the 8th Battalion, they too were badly mauled in the attack. The Commanding Officer of the 7th Scottish Rifles, Colonel Boyd-Wilson, was killed while leading the battalion forward. Many more officers were killed and wounded, command falling onto junior officers and sergeants. The Turkish line was taken in places, but enemy reinforcements made it almost impossible to consolidate any gains that had been made.

At one point in the action a Turkish grenade fell into a section of trench packed full of men of the 7th Scottish Rifles. Lance Corporal Ross and Private Young, realising the devastation the grenade would cause in such a confined space occupied by their comrades, tried to stifle the effects of the blast. Lance Corporal Ross put his foot on the grenade while Private Young bundled up a greatcoat and held it over the grenade with his hands and body. The grenade exploded, badly injuring the two men, but saving their comrades from harm. For their actions both Lance Corporal Ross and Private Young were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

In the early hours of 29th June, the survivors of the 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles were relieved and withdrawn to the reserve lines. The next day was spent trying to clear as many wounded and dead from the front line trenches as was possible. It was then that the enormity of the losses sustained by the two battalions became apparant. A roll call on 30th June revealed that the 7th Scottish Rifles had lost 14 Officers and 158 Other Ranks killed or missing, with a further 104 men of all ranks being wounded. The 8th Scottish Rifles had sustained terrible losses – 15 Officers and 334 Other Ranks killed or missing, and 124 men of all ranks wounded. The majority of those reported as missing were never seen again, most likely killed or having died of wounds. Among those killed was a young Private called John Gray of the 7th Scottish Rifles. The day before the attack he had written to his mother in Glasgow; it would ultimately be his last letter home:

…Well Mother about myself, I’m keeping A1 now, and pushing through this life as best I can. It’s not a pleasant one, but it’s got to be done. Things have been very quiet here lately, but as the saying goes “there’s always a calm before a storm.” We’ve been resting now since Thursday, so that I think we’ll be going back to the trenches tonight. Well Mother, as there’s nothing more to say at present Ill start summing up, give my best love to Liz and all at home, and tell all my friends I was asking for them… I’ll draw to a close now, with the hope that it won’t be many weeks or months before we’re sailing back to Bonnie Scotland.

The next time one hears the name ‘Gallipoli’ spare a thought for the thousands of soldiers from all countries who fought and died there in the First World War, and remember the hundreds of men of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) who fell at Gully Ravine.

Comments: 10