The Battle of Hamilton 1936

The Battle of Hamilton, July 4th-5th 1936

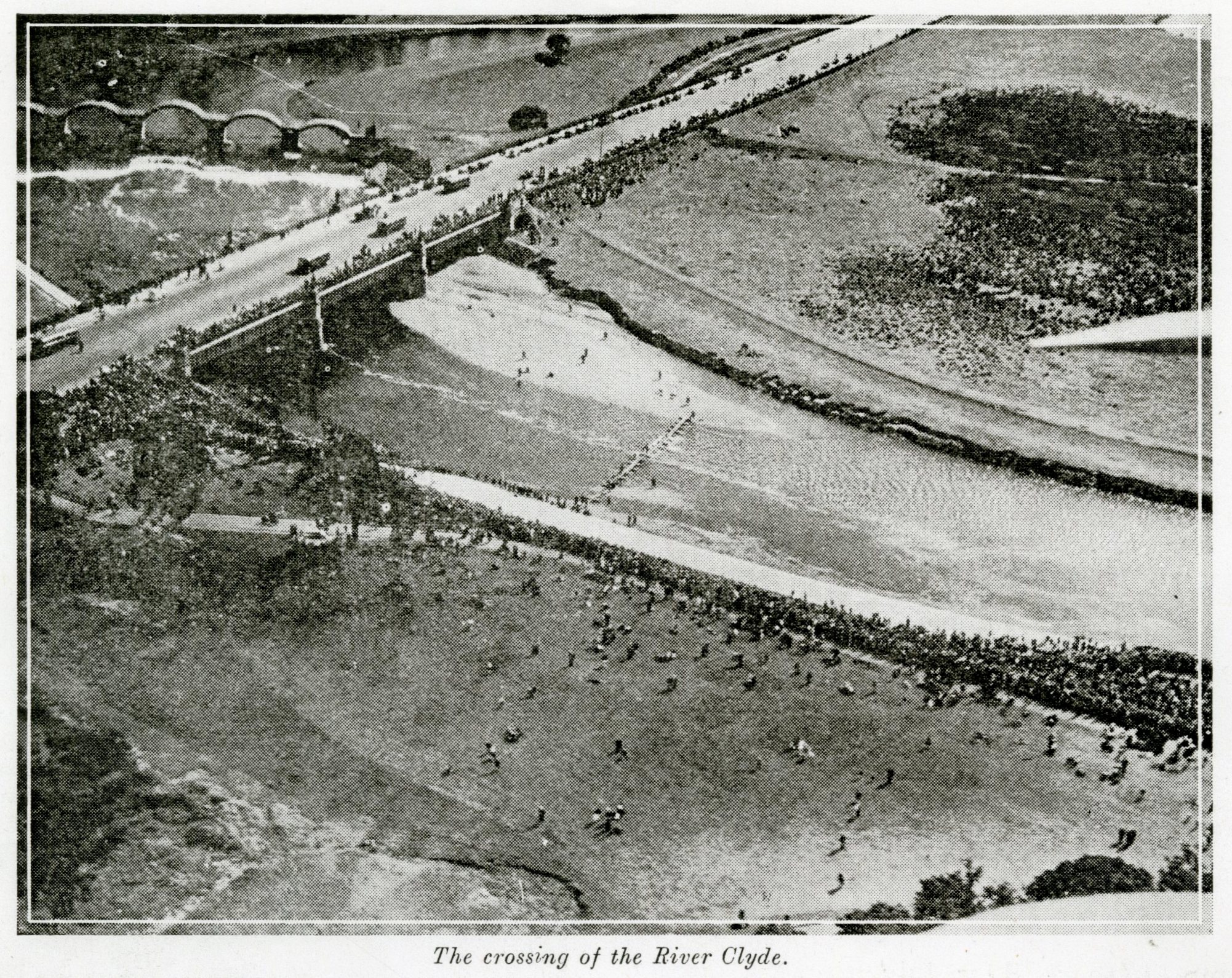

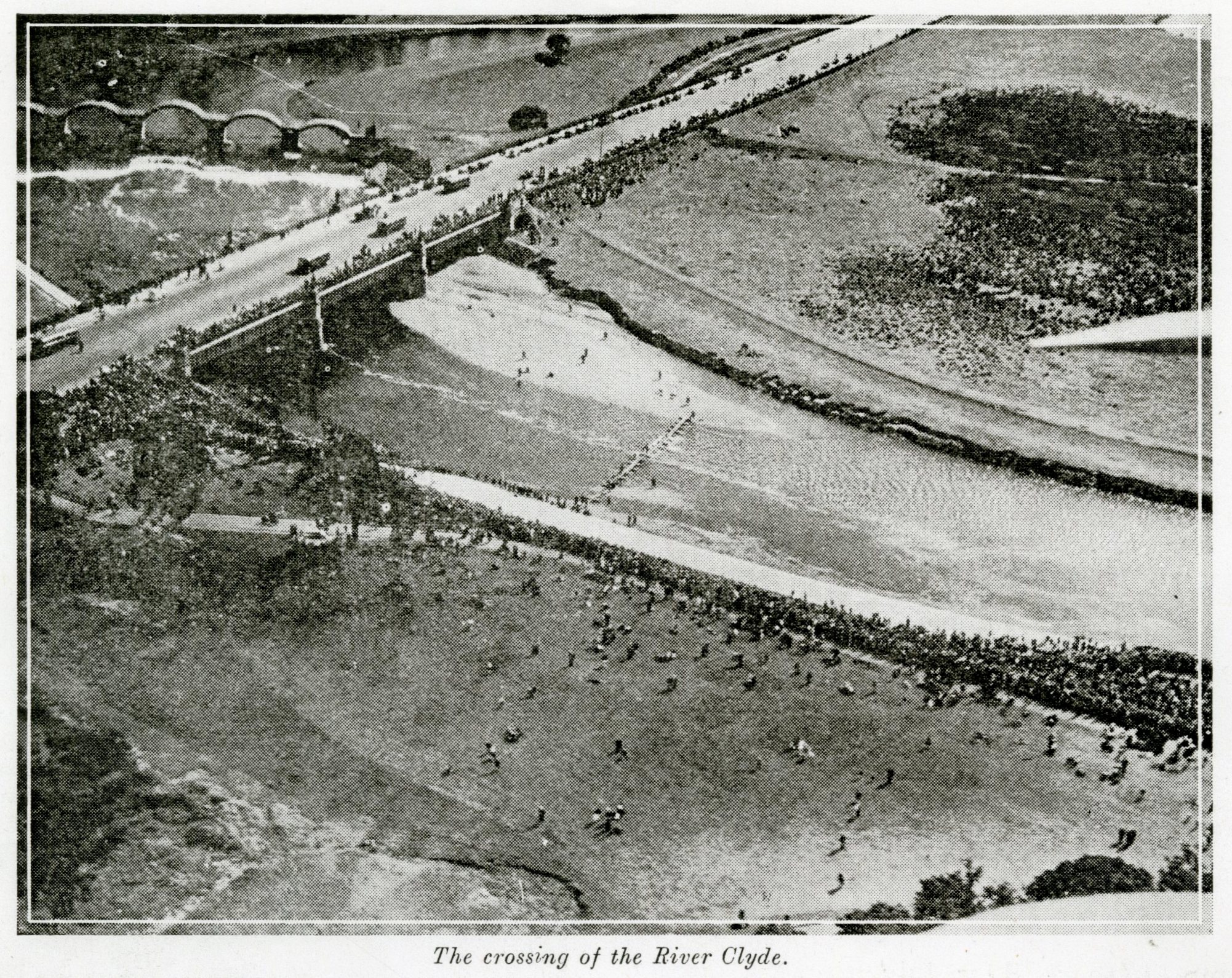

On Saturday the 4th of July 1936, the 6th Territorial Battalion of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), with close air support from 602 “City of Glasgow” Bomber Squadron of the Auxiliary Air Force, fought their way across the River Clyde from Motherwell to Hamilton. Their objective: to retake Hamilton from an enemy force. The enemy had blown up the Clyde Bridge on the main road down from Motherwell, so the 6th Battalion had to construct a pontoon bridge and assault the banks of the Clyde on the Hamilton side before fighting their way into the town itself, all the while under hostile fire. Above them, the aircrews of 602 Squadron would attempt to suppress the enemy fire before attacking targets in Hamilton itself. A huge and complex undertaking for the part-time soldiers and airmen to attempt.

It sounds like the plot of an epic war film and in a way it was, for this was the huge mock battle that was staged as an exercise that summer. According to the press reports, it was one of the largest military exercises ever to be held in public in Scotland up to that point in time. An estimated 35,000 people would watch the exercise take place with crowds crammed onto the “blown up” Clyde Bridge watching the action unfold above and below them.

It was Lt. Colonel Galloway, the Hamilton Depot’s Commanding Officer, who had drawn up the exercise. The scenario was that war had broken out four days earlier. The “Westland” army, in retreat, had destroyed the bridge and seized a major ammunitions factory in the then village of East Kilbride. The men of the 6th Territorial Battalion under Lt. Colonel Kerr and 602 Squadron, then still under the command of The Marquis of Clydesdale, were the elements of the “Eastland” forces tasked with retaking Hamilton and establishing the Clyde bridgehead for the push onto East Kilbride itself. With the full cooperation of both Motherwell and Hamilton Town Councils, the free use of both the Motherwell Park and the Hamilton Low Parks were granted and an enclosure was built on one side for the family and friends of the soldiers taking part to watch from. It had been well advertised in the newspapers beforehand and many were keen to see their local soldiers at work, so huge crowds had gathered on the surrounding hillsides and on the bridge itself.

Among the crowd, albeit mostly ignored, was a small but vocal anti-war demonstration by members of the Communist Party, complete with a loudspeaker equipped van proclaiming “Mock war today, real war tomorrow!”

Arriving from their billets in Newmains, the 15 officers and 270 other ranks* prepared their kit at lunchtime, ready for the assault. After mustering at the Motherwell Drill Hall at 3.30pm, the men then moved out and assembled at their first objective, the Motherwell Park river bank, by 4.20pm. Today, the banks where the River Avon meets the Clyde are covered by dense trees and the M74 Motorway runs close to the Hamilton side. But in 1936 they were clear and open, a perfect location for a bridging assault.

Aerial photograph of the bridging operation as published in the Covenanter a few months later

The 101st Field Brigade, Royal Artillery gave them covering fire in the shape of smoke bombs to simulate the shellfire and the sleek, silver Hawker Hart biplanes of 602 Squadron swooped down and proceeded to lay a covering smokescreen. A kapok pontoon footbridge was then thrown across the Clyde by the men of D Company, a difficult task as the previous days rain had swollen the river considerably and strengthened the current. The bridge was constructed along the Motherwell bank and with men already in the water was swung out into the flow of the Clyde. Once it had been secured on the Hamilton bank, the men of A and C Companies ran across to secure the bridgehead. Their only casualty was a Sergeant who fell headlong into the river, much to the vocal and unsympathetic amusement of the spectators! The men of D Company were later singled out for fulsome praise for their skill and quick reactions in building and securing the bridge into place, despite the river conditions, by their commanding officers. The press reporters recorded that the crowds on the Clyde Bridge were quite taken by seeing the soldiers dressed merely in bathing costume, due to the length of time they had to spend in the water.

With A and C Companies safely across the Clyde the bomber crews of 602 Squadron now turned their attention onto the enemy positions in the town and the Low Parks as the Cameronians fought their way in. A series of low-level attack runs commenced to support the advancing troops, which would have been a spectacular sight and sound for the citizens of Hamilton. This must also have been a surreal moment for 602’s commanding officer, attacking the remnants of the Hamilton Palace which his father had inherited in 1895 on becoming 13th Duke of Hamilton and where he himself had spent part of his childhood. Thousands of rounds of blank ammunition were exchanged between the pilots and gunners and the anti-aircraft machine gunners on the ground, to their evident enjoyment! The Marquis of Clydesdale was of course well known for flying the first aeroplane over Mt. Everest in 1933, so the squadron and the regiment were both very much linked through their connections with the Douglas-Hamilton family. On board one of the Harts to observe the exercise from above was Major General Fortune, the then commanding officer of the 52nd Lowland Division.

An unplanned addition to the exercise then took place which was definitely not on Lt. Colonel Galloway’s schedule. The commotion caused by the low flying aeroplanes and gunfire had an unexpected effect on some in the Low Parks; a herd of the legendary white cattle grazing beside the Hamilton Mausoleum got so annoyed with the noise that a stampede then broke out in the direction of the troops. However, on encountering the men of the 6th Battalion, the cattle tactically withdrew back to the relative calm of the former Ducal resting place.

By 6.30pm all objectives had been achieved according to the exercise umpires, the 6th Battalion had secured Hamilton and had pushed out the enemy forces. For this the troops were rewarded with an issue of tea and pies! The men then fell in and with the Battalion Band at the front of the column they proudly marched off through Hamilton to camp for the night in the Cadzow Rifle Ranges. There, the men settled down for some fine evening entertainment in the shape of some competitive inter-company boxing bouts.

The following day, there was an inspection of trench fortifications prepared earlier in the week by the troops and demonstrations of section and platoon tactics and manoeuvres. This brought the exercise to an end and the Battalion was dismissed that afternoon to great praise and compliments from all of the senior officers present for a very successful two days of operations.

Peter Kerr, Low Parks Museum, 2018

*As quoted in “The Covenanter”, contemporary press reports said 400 men took part but this number might have included the Artillerymen and other regimental officers and personnel present.

Comments:

Posted: 05/07/2018 by PeterKerr in Events

Families and the Territorial Force

Tomorrow is the anniversary of the 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles’ attack on Gully Ravine on the Gallipoli peninsula. Based on cold statistics this was the worst single day The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) suffered in the entirety of the First World War. While it would be many weeks for the scale of the losses to become known at home, we now know that between the two battalions over 470 men lost their lives in the attack. Not even in the opening phase of the Battle of Loos, in which many more battalions of the Regiment were engaged, would the casualties be matched. I don’t intend to go into the action at Gully Ravine in any great detail in this post; you can learn more about the 7th and 8th Battalions’ experience in that battle by reading my previous post marking the 100th anniversary. But this anniversary does provide an opportunity to remember the part played by the Territorial Force battalions of the Regiment as a whole, and the terrible losses felt by the communities these units represented.

The Territorial Force was created on 1 April 1908, the successor to the Volunteer Force of the mid-19th century. The men of the Territorial Force were ‘part time’ soldiers in that they remained in their civil employment but attended regular training weekends and drill nights where they were given a semblance of the training given to those soldiers of the Regular Army. Four battalions of the Territorial Force came under the parentage of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles); the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles. The 5th, 7th and 8th Battalions covered Glasgow, while the 6th Battalion belonged to Lanarkshire, and its headquarters were in Muirhall, Hamilton (now the site of Cameronian House – home of the Procurator Fiscal’s office and job centre). These battalions truly were microcosms of the areas they represented; the majority of men would live and work within the Battalion’s recruiting area, and many of the men would work together in the same businesses and industries. Many of the officers were drawn from the management and directorship levels of the companies and factories in which the men worked, while younger officers were often university students or graduates who had been attached to an Officer Training Corps. It was not uncommon for a private soldier or non commissioned officer of the Territorial Force to have their manager from their civilian occupation as a battalion officer.

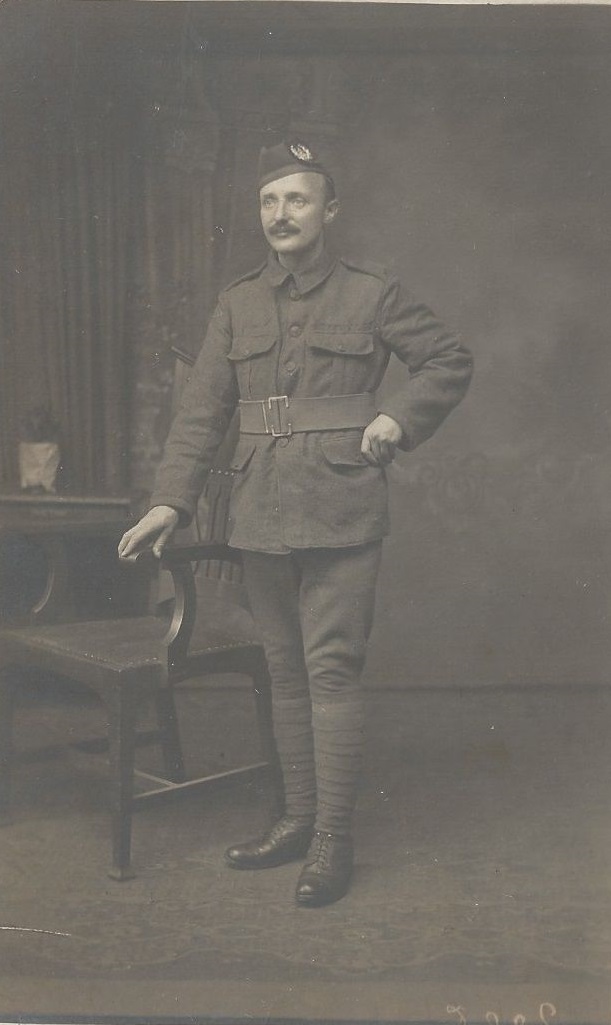

One such example of this is Robert Downie of Hamilton; a draughtsman who was also a soldier of the 6th Scottish Rifles. In civilian life he worked in the offices of local architect Gavin Paterson, who also happened to be Lieutenant Colonel, commanding the 6th Scottish Rifles. Robert Downie did not survive the First World War. He went to France with the 6th Battalion in March 1915 as a sergeant and was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for gallantry at Festubert, in June of that year. Downie was later commissioned and was also awarded the Military Cross for his actions when his battalion led the attack to push the German forces out of the French village of Clary, in late October 1918. Captain Robert Downie was killed on 6 November 1918, just five days before the Armistice.

Sergeant Robert Downie, 6th Scottish Rifles

The Battle of Festubert, in which Robert Downie earned his DCM, was the first major engagement in which the 6th Scottish Rifles took part. The Battalion suffered heavy losses, which were closely felt by the towns and villages of Lanarkshire from which the men of the battalion called home. By their nature, Territorial Force battalions were far likelier to contain men from the same families as might be found in the Regular battalions of the Army. Brothers, brothers-in-law, cousins, and even fathers and sons were found serving together in the Territorial Force battalions. Searching through casualty notices in the Motherwell Times yesterday, I came across this particularly heart breaking letter:

Letter from Private James Dickson – to his parents in Motherwell

“I regret very much to tell you that Jamie Baird died yesterday afternoon at 2.30. I got word yesterday morning that he was lying in a hospital barge in a canal about an hour’s walk from where we are billeted, so I got a pass immediately after parade, and set out to see him. I just got to the barge when a sergeant of the R.A.M.C. came down the gangway, so I asked if I could see Sergt. Baird, as he was a brother-in-law of mine, He had a slip of paper in his hand, and he showed me it with Jamie’s name on it, and said that if I had been ten minutes sooner I would have seen him pass away. He told me he died very peacefully, and I went on and saw him lying where he died. He was quite warm, and looked very nice. I asked what the nature of his wounds were. He told me he had one in the abdomen and one on the hand. I asked when he would be buried, so they sent me to another place further on and they told me there that he would be buried at six o’clock, so I hurried off to our billet and got a party of our company, and we laid him to rest in a nice little graveyard in a village which I can’t give you the name of just now, as we are not allowed to do so. Just break the news as gently as possible to poor Annie (Mrs Baird). I am heart sorry for her, and all my little nieces and nephews. They will miss their father, but he fell fighting and was brave to the last, although that is very little consolation to those who are left behind. I asked the ambulance sergeant major if he would put up a little cross and he promised to do so, and they told me that all the articles that were his would be sent to the base and then on to his wife.”

James Baird was married to Annie Dickson, Private James Dickson’s sister. James and Annie had seven children – the ‘little nieces and nephews’ mentioned in Private Dickson’s letter.

Sergeant James Baird, 6th Scottish Rifles

Two brothers from Motherwell, Robert and Isaac Devon, were also serving in the 6th Scottish Rifles during the Battle of Festubert. Isaac, who was soldier-servant to Captain Lusk, was wounded but survived, while Robert was wounded and died the following day.

Looking back to Gully Ravine, many families from Glasgow suffered multiple blows when the full extent of the losses among the 7th and 8th Battalions became known. A chilling newspaper article in the Daily Record of 27 July 1915 lists a number of casualties from the 8th Scottish Rifles. Printed at the head of the list is an appeal from one mother looking for information on her sons:

“Mrs. Annie Murdoch, 117 Alexandra Parade, has received intimation from Territorial Force Headquarters at Hamilton that her three sons – Gavin (21), Ronald (19), and William (17) – all in the 1/8th Cameronians, have been missing since 28th June. All three were in H Company.

Mrs. Murdoch has other two sons serving King and country – Norman (25) who is an electrical engineer in the Transport Department now in Flanders, and Hugh (15) in the Royal Navy, now on his way to the Dardanelles. Mrs. Murdoch will be glad to hear any tiding of her three missing sons.”

I could find no further mention of the Murdoch brothers in subsequent editions, however the Commonwealth War Graves Commission online register does record the names of a Gavin Murdoch, Ronald Murdoch, and William Murdoch, all having died on 28 June 1915 serving with the 8th Scottish Rifles. All three men are commemorated on the Helles Memorial, suggesting their remains were never identified. There are no obvious commemorative records for Hugh or Norman Murdoch, so one can hope that they at least returned safely to their mother in Glasgow at the Wars end.

This photograph shows the officers of the 8th Scottish Rifles, taken in late 1914.

Rear row, left to right: Lt E. Maclay*, 2Lt R. Humble, Lt J. T. Findlay*, Lt W. N. Sloan, Lt & QM H. Bowen*, 2Lt T. Stout*, 2Lt A. R. Tillie*, 2Lt W. S. Maclay*, Lt G. H. Crichton, Middle Row: 2Lt D. S. Carson, Capt C. J. C. Mowat*, 2Lt T. L. Tillie, Lt H. McCowan*, Captain W. C. Church*, Capt A. B. Sloan (RAMC), Capt H. A. MacLehose, Lt R. C. B. Macindoe*, Lt G. A. C. Moore*, Lt A. D. Templeton*, 2Lt J. W. Scott*, Capt E. T. Young*, Front row: Capt W. T. Law, Capt J. W. H. Pattison, Major R. N. Coulson, Major J. M. Findlay, Lt-Col H. M. Hannan*, Capt C. G. Bramwell*, Capt J. M. Boyd, Capt C. A. D. Macindoe* (* denotes died or killed in the War)

A few months after this photograph was taken, the Battalion would depart for Gallipoli. Of the 29 men shown in this photograph, 17 would never return home. Eleven of those were killed or died in the action at Gully Ravine on 28 June 1915. There are two pairs of brothers in this photograph; the Tillies and the Maclays, all young Second-Lieutenants. Two of the officers shown were also cousins; Lieutenant R. C. B. Macindoe and Captain C. A. D. Macindoe.

Talbot Lee Tillie was badly wounded on 28 June – his life was saved by one of his Sergeants, Stephen Miller, who risked his own life to drag the wounded officer back to the relative safety of the British lines. Arnold Reed Tillie did not survive the War. He had transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and was killed on 11 May 1916. A third Tillie brother, John Archibald, died on 19 July 1918, serving with the Black Watch.

William Strang Maclay died on 25 June 1915, in the lead up to the attack on Gully Ravine. His brother, Ebenezer, survived Gully Ravine, and a subsequent attack launched by the survivors of the 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles on 12 July 1915. Ebenezer was invalided home to the UK in August 1915, and subsequently transferred to the Scots Guards, with whom he was serving when he was killed on 11 April 1918.

Cecil and Ronald Macindoe, cousins, were both killed on 28 June at Gully Ravine.

Two of the officers pictured had also represented Scotland in Rugby; Captain W. C. Church, and Captain E. T. Young. Captain Church’s name is soon to be added to a new panel in the University of Glasgow Memorial Chapel, commemorating 19 men previously missing from the University’s roll of honour.

I can think of few other photographs that demonstrate the human cost of the War as clearly as this. The details listed above are, of course, just a few individual stories from the thousands that make up the Regiment’s losses in the First World War, but for me, they exemplify the particularly high price paid by all Territorial Force battalions of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

Comments:

“We have to go now, Sir! It is time for us to go.”

These were the immortal words spoken by Lieutenant Colonel L. P. G. Dow to the Commander-in-Chief in Scotland on 14 May 1968, signalling the time had come for the 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) to disband.

Watercolour of the 1st Battalion’s Disbandment Service, by Tom Carr, 1968

14 May 2018 marks the 50th anniversary of the Disbandment of the 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), as a result of reductions to the UK Defence budget. Despite being raised in 1689 (as the Earl of Angus’ Regiment), The Cameronians were the junior regiment of the Lowland Brigade and it was to them that the bitter choice to amalgamate or disband was given. As it would not have been possible to preserve its unique history and traditions on amalgamation with any other regiment the painful decision to disband was taken.

So it was that on May 14 1968, at Douglas, the 1st Battalion The Cameronians ‘marched from the Army List and into history’. The majority of officers and men remained in the Army, transferring to other regiments and Corps. The name of the Regiment lived on through companies of the Lowland Volunteers and the Army Cadet Force until 1996 when they were rebadged and affiliated to other regiments. Further reduction of the army in 2006 brought the end of the names of all the Scottish infantry regiments, which were merged into the newly created Royal Regiment of Scotland.

While The Cameronians are no longer a part of the British Army, they are remembered with pride across the world; in foreign lands where they fought to liberate the oppressed and help preserve peace, and in Lanarkshire, their home. Low Parks Museum is the proud custodian of The Cameronians regimental collections, through which the Regiment’s name lives on in perpetuity.

To commemorate this momentous occasion in the Regiment’s history, we have created a small display within Low Parks Museum showing some key objects from the regimental collection that relates to the disbandment of the 1st Battalion. One of the objects in this display is the insignia of a Commander of the Swedish Order of the Sword, which had been presented to Lieutenant Colonel Dow on the morning of the disbandment service. The honour was bestowed on behalf of His Majesty King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden, Colonel in Chief of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

Neck badge of a Commander of the Swedish Order of the Sword, presented to Lt-Col L. P. G. Dow

It was possibly with mixed emotions that Dow received such an honour, given that his first opportunity to wear it was at the disbandment of his Battalion. As Commanding Officer, Dow had the painful task of formally disbanding the 1st Battalion – bringing almost 300 years of service to an end. The date chosen for the disbandment service was symbolic; the anniversary of the founding of the Earl of Angus’ Regiment 279 years earlier. Douglas was where that regiment had been raised and it was only fitting that that is where the disbandment of the 1st Battalion should take place.

The first Commanding Officer of the Earl of Angus’ Regiment was William Cleland, the young, veteran commander of Covenanting forces at Drumclog and Bothwell Bridge. Cleland had the honour of commanding his regiment in it’s first victory, at Dunkeld on 21 August 1689. The victory was tainted by tragedy as Cleland was among those killed in the action. His sword would go on to become one of the Regiment’s most treasured relics, and was placed on the Communion Table on the day of the disbandment, a physical reminder of the first Commanding Officer of the Regiment.

The sword of Colonel William Cleland

Cleland was a man of words, and indeed left behind a legacy of poetry in addition to his accomplishments as a soldier. After his death, a poem dedicated to him by an unknown author was included in a collection of Cleland’s works.

It is titled ‘An Acrostik Upon His Name’ and reads:

Well, all must stoop to death, none dare gainsay.

If it command, of force we must obey:

Life, Honour, Riches, Glory of our State

Lyes at the disposing Will of Fate:

If’t were not so, why then by sad loud thunder

And sulph’rous crashes, which rends the skies asunder

Must a brave Cleland by a sad destiny

Culled out a Victime for his country die.

Lo, here’s a divine hand, we find in all,

Eternal Wisdom has decreed his fall.

Let all lament it, while loud fame reports,

And sounds his praise in Country, Cities, Courts.

No old forgetful Age shall end his story,

Death cuts his days but could not stain his Glory.

Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Dow, last Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), wrote his response in 1968, in dedication to William Cleland:

Another Acrostik Upon His Name

Would you approve of how the tree has grown?

I like to think so. You bequeathed your own

Love of a harassed land and honest cause,

Love which without advertisement or pause

Inspired a hundred Clelands less renowned

And warms platoons of Thompsons in the ground,

Men who have walked this road and shared this view.

Campbell and Lindsay forged the sword with you.

Lit by your pride they handed on the text,

Each generation shaping up the next.

Lindsay and Campbell finish it today.

Axed lies the tree. Now put the sword away,

No old forgetful age will end our story,

Death cuts our days but could not stain our Glory.

The first and last Commanding Officers, William Cleland and Leslie Dow, share one other, remarkable connection. Leslie Phillips Graham Dow was baptised on 16 February 1926 in the Cathedral Church of St. Columba, Dunkeld, the final resting place of Lieutenant Colonel William Cleland.

In 2007 a tree was planted at the National Memorial Arboretum, dedicated to The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). It is fitting that the accompanying plaque bears the last two lines of Colonel Dow’s poem, quoted above.

The plaque accompanying the Regimental Tree, at the National Memorial Arboretum.

Comments:

Posted: 11/05/2018 by BarrieDuncan in Collections, Events

ID’ing Your Cameronian 1914-18

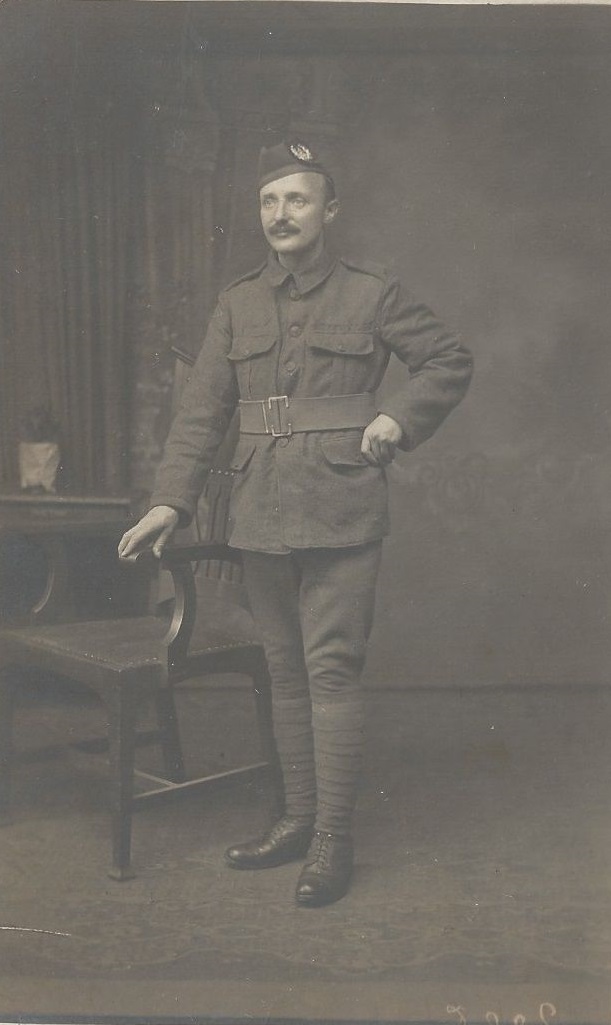

One of the identifying features of a British soldier is the various insignia and trappings of their regiment. The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) are no exception to this. On service during the First World War, members of the regiment wore a uniform and used kit the same as other soldiers of the British Army, yet as we’ll see they retained certain regimental distinctions which can help you identify a Cameronian in a crowd.

4th Army School in France. Can you tell which one of these soldiers is a Cameronian? (Photo Courtesy of James Taub)

THE UNIFORM

Like other soldiers of the British Army when in the field the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) wore a khaki coloured wool uniform. Officially referred to as the 1907 Service Dress uniform. It consisted of trousers and a tunic. The tunic includes much of what you need to identify a Great War serviceman as a member of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

Black Buttons- As a rifle regiment, the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) were allowed the distinct honour of wearing blackened horn buttons. While on their rifle green dress uniform, they would sport buttons with a horn and thistles distinct to the regiment, during the Great War the buttons worn on service dress were the standard blackened horn button issued to all rifle regiments.

A Cameronian wearing the standard 1907 Service Dress uniform. He is sporting the regiment’s black buttons and shoulder titles. (Courtesy of James Taub)

Shoulder Titles- Although there was still conflict between the 1st and 2nd Battalions at the outbreak of the First World War regarding being called ‘Cameronians’ or ‘Scottish Rifles’, all soldiers of the regiment were issued with brass “SR” shoulder titles. These would be blackened (generally with boot polish) to acknowledge the soldier’s status as a member of a rifle regiment.

First World War SR shoulder title. (CAM 2007.39.3)

HEADWARE

The hats and helmets of the regiment would change as the war progressed. As part of the dress uniform and the initial 1914-15 uniform, soldiers would be wearing the traditional rifle green glengarry with the regimental badge. In mid-1915, a small bonnet was introduced. By early 1916 the tam o’shanter was making its appearance for wear behind the lines. Simultaneously brodie helmets were introduced for front-line wear.

Reenactors donning the glengarry, tam o’shanter, and helmet. The three main pieces of headgear for the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in the First World War.

Comments:

For Bravery in the Field – a follow up

Yesterday I wrote about the men of the 10th Scottish Rifles who went on a patrol into no man’s land on 21st December 1917. Sergeant John Wilson, from Hamilton, was one of the two men who returned to the British lines three days later, on Christmas Eve.

This morning I found some additional information that sheds some light on what happened to the brave Sergeant in the years following the First World War.

While searching through online newspaper articles, I came across an account in The Scotsman of King George and Queen Elizabeth’s Royal visit to Lanarkshire on 4th May 1938. The article recounted that, following a reception at Hamilton Town House, Their Majesties were making their way to their car when they observed in the crowd, a group of 14 men wearing medals. The King enquired who the men were, and was introduced to them by the Provost. The men were all limbless ex-servicemen from the area, and among them was none other than Sergeant John Wilson MM:

Mr Dodd [the leader of the group of ex-servicemen] drew His Majesty’s attention to John Wilson, holder of the Military Medal, who lost both his legs while serving in France. “How do you manage to get along?” inquired His Majesty, and Mr Wilson modestly replied. “Oh, fine.”

I then started looking through the regimental magazine of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), titled The Covenanter, and found an obituary notice for John Wilson, published in the January 1945 edition. It reads:

Death of Old Cameronian

We Regret to Record the death of Mr John Wilson, a linotype operator on the staff of “The Hamilton Advertiser” for over 35 years. Mr Wilson served as a non-commissioned officer in the Great War with the 6th Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He was twice wounded, once at Festubert and again in 1918 in an action in which he was awarded the Military Medal. He lost one of his fingers at Festubert. In 1918, he received a severe gunshot wound and suffered severely from frost-bite through forced to remain in “no-man’s-land” for three days. He had both legs amputated below the knee as a result of this experience. Following his discharge from the Forces, he returned to his civilian occupation and, because of his disability, was trained as a linotype operator. Even with two artificial legs he was very agile and served the firm faithfully and well up till the time of his death. There is no doubt that his general health suffered as a result of his war service, but “Jock”, as he was familiarly called, bore his illness with true Cameronian fortitude and was never heard to utter one word of complaint. Mr Wilson was one of the pioneers in the formation of Hamilton and District Branch of the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen’s Association, and was also an enthusiastic member of the Regimental Association of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). “Jock” also took a keen interest in “The Covenanter”, and in his capacity as a linotype operator he was given the job of setting-up the type for the magazine. This afforded him a great deal of pleasure and kept him very much in touch with the activities of his old Regiment. At the funeral to Bent Cemetery, Hamilton, his old Battalion was represented by the presence of its honorary colonel, Lieut. Col. J. C. E. Hay, C.B.E., M.C., T.D., D.L.

Further notifications in The Covenanter reveal that John Wilson bequeathed his medals to The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) regimental museum, and also bequeathed a sum of money to the Regimental Museum Fund.

South Lanarkshire Council’s Bereavement Services were very helpful when I made enquiries about the whereabouts of Sergeant Wilson’s grave, and armed with plot details and a map I made my way there to pay my respects. It would appear, however, that Sergeant Wilson’s grave lies unmarked; perhaps not surprising as his obituary notice made no mention of any surviving family who might have arranged a headstone. I placed a memorial cross in a tree as near as I could estimate where Sergeant Wilson’s grave might lie.

On Christmas Day, safe and warm and in the company of my family, I’ll raise a glass and spare a thought for Lieutenant Ewen, Lance Corporal Thomson, Private Aberdeen, and of course, Sergeant John Wilson, and what they went through in no man’s land 100 years ago.

Comments:

Log in