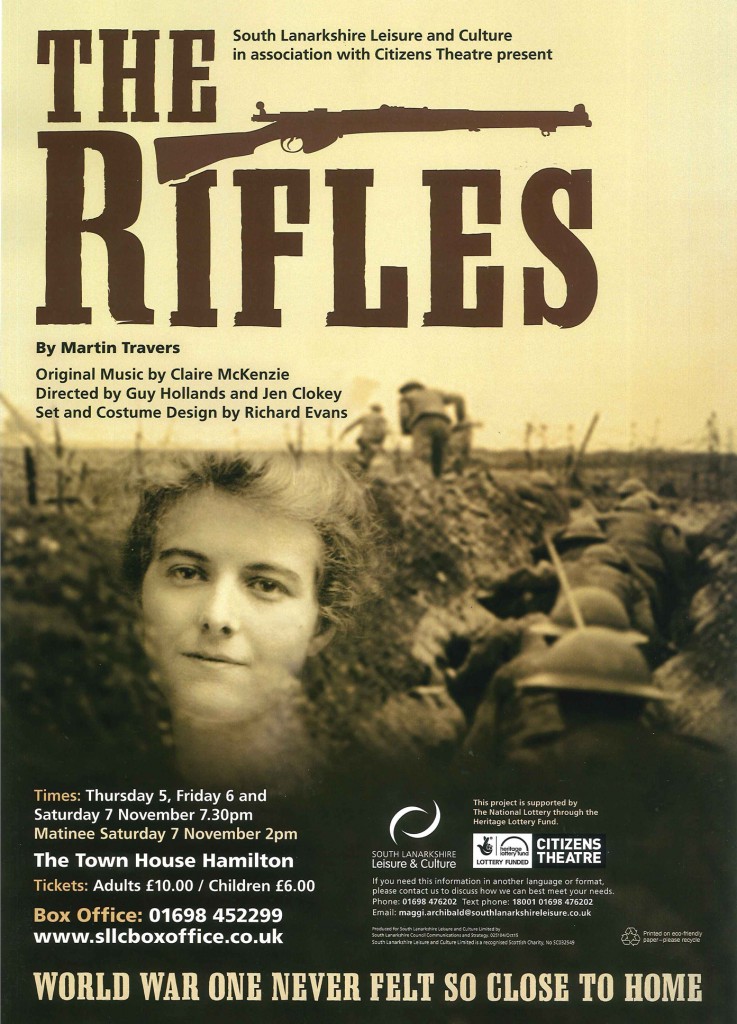

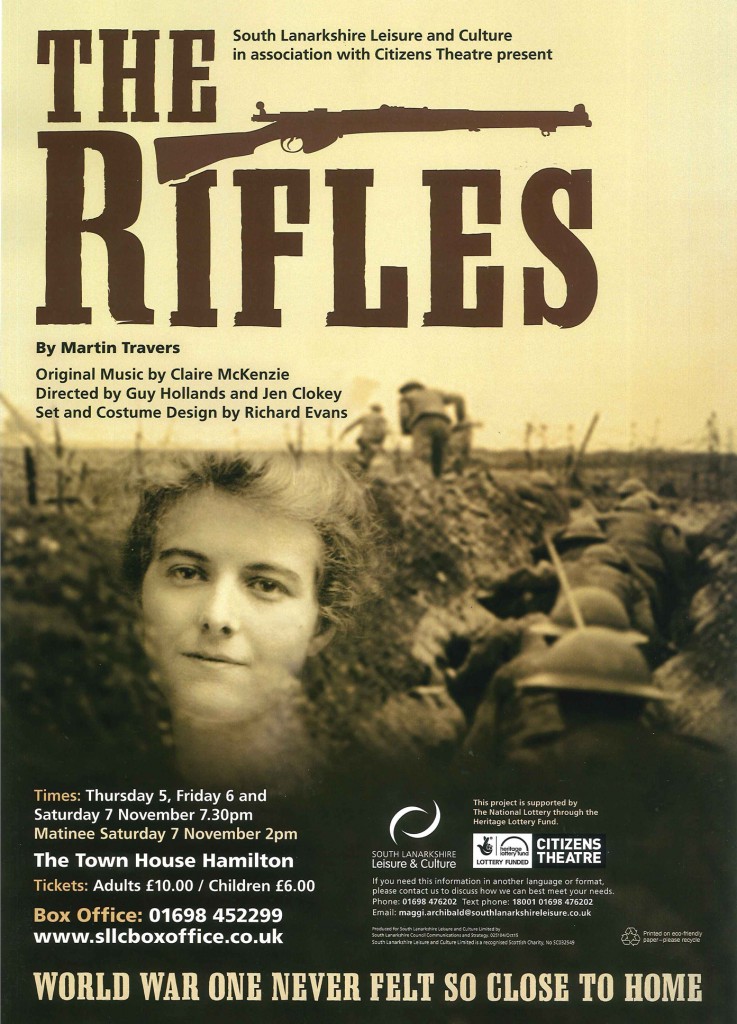

The Rifles – coming soon to The Town House Hamilton

World Premiere

Packed with new songs and some old favourties that are intertwined with a Lanarkshire love story and the families’ struggle back home, The Rifles recounts the Cameronians harrowing experiences in France during the First World War.

A world premiere musical production by a large ensemble cast from South Lanarkshire High Schools supported by a live professional band. The Rifles is the brand new musical play from the creative team that brought the smash hit Divided City to Lanarkshire in 2013.

Part of South Lanarkshire Leisure and Culture’s First World War Project:

Local Heroes – The Untold Stories of The Cameronians in their Own Words

Times: Thursday 5, Friday 6 and Saturday 7 November 7:30pm

The Town House Hamilton

Tickets: Adults £10.00 / Children £6.00

Box Office: 01698 452299

www.sllcboxoffice.co.uk

Comments:

The Battle of Loos

Friday 25th September marks the anniversary of the Battle of Loos. Although later eclipsed in scale by the Battle of the Somme in 1915, at the time it was the largest attack launched by the British Expeditionary Force of the War. Loos is also significant as it was in this battle that the British Army used poisoned gas for the first time.

Four battalions of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) were involved in the Battle, representing the regular army (1st Battalion), the Territorial Force (1/5th Battalion), and the recently formed service battalions of the New Army (9th and 10th Battalions).

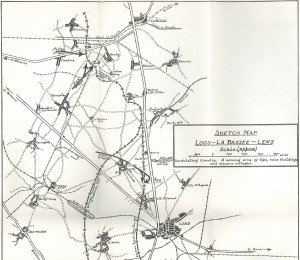

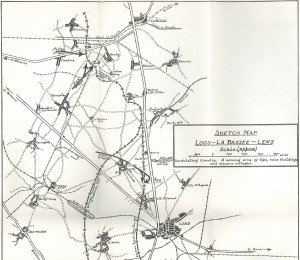

Map showing the positions of the Battalions of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) involved in the Battle

Loos was a mining town, and the surrounding landscape was covered in mine workings, pit heads, and slag heaps, and would have no doubt felt quite familiar to the hundreds of men from Lanarkshire who would take part in the Battle, many of whom were miners in civilian life. Even today, the slag heaps of the famous ‘Double Crassier’ dominate the skyline south of Loos.

Double Crassier, as viewed from Dud Corner Cemetery

The attack commenced at 6:30am on the morning of Saturday 25th September. Gas was released in front of the 15th Division’s position 40 minutes ahead of the attack. Unfortunately the windy conditions resulted in some of the gas drifting back towards the British front, gassing their own men.

Many of the objectives of the attacking force were met that day, but a failure to bring up reinforcements in time to take advantage of gains made saw the advance falter. The 10th Battalion in particular had made steady gains, battling their way through Loos itself and on to the secondary objective of Hill 70. There the British forces encountered heavy resistance from the German defenders and it was found impossible to maintain hold of the hill.

The 9th Battalion attacked in support of the 10th Battalion Highland Light Infantry, who had suffered heavy casualites in the initial attack. A second attack by the 9th Scottish Rifles just after noon on 25 September was repulsed with heavy casualties.

The 1st and 1/5th Battalions were the Support and Reserve battalions of the 19th Brigade in its attack. When the initial attack by the leading battalions had been halted; orders were received by the 1st Battalion to prepare for a fresh advance. Thankfully the order was later cancelled when it was pointed out by the Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion that the chances of success of any further attack was unlikely.

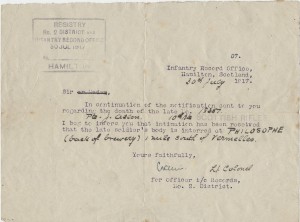

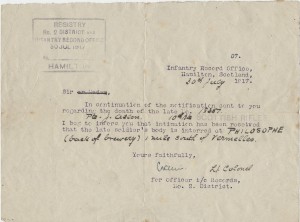

One of the casualties of the Battle was Private Jack Allen of the 10th Battalion who died of wounds on 27th September. Likely wounded on 25th, Private Allen was taken to the brewery at Philosophe where a Field Ambulance of the Royal Army Medical Corps had been established, and here he succumbed to his wounds. He was buried nearby in what is now Philosophe Cemetery. Sadly, the exact whereabouts of Private Allen’s grave were either never fully recorded, or were later lost; he is now commemorated on the Loos Memorial at Dud Corner Cemetery. A letter in the museum collection does however record that he had been buried at Philosophe.

Letter relating to burial of Private Jack Allen

It is difficult to establish exactly how many soldiers of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) became casualties in the Battle of Loos. Initial reports in Battalion war diaries often record those who had been killed as ‘Missing’, and it would be some time before these men were confirmed to have died. The publication Soldiers Died in the Great War records that 413 soldiers from the The Cameronian battalions at Loos died on 25th September 1915. Many of the soldiers who died have no known grave, and are recorded on the Loos Memorial at Dud Corner Cemetery. This cemetery occupies the site of the Lens Road Redoubt, one of the German strongholds taken by the 15th (Scottish) Division on the first day of the Battle.

Dud Corner Cemetery. The panels on the outer wall record the names of those whose graves are unknown.

Comments:

Posted: 24/09/2015 by BarrieDuncan in First World War

Lt. Col. Douglas Graham Moncrieff Wright

Douglas Graham Moncrieff Wright was born in Rangoon, Burma on 7th June 1893. He was the only child of Lena (née Graham) and John Moncrieff Wright of Kinmonth, Bridge of Earn, Perthshire. He was educated at Glenalmond College, Perth and then in 1912, attended the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. After graduation in 1913, he was gazetted to The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) and joined the 1st Battalion at Maryhill Barracks.

With the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Moncrieff Wright was deployed to France with The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) 1st Battalion. He received the Military Cross and bar for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty and was mentioned in dispatches twice. On 19 June 1916, The London Gazette, it was noted that, ‘He commanded a bombing attack on the enemy trenches. He led this attack with great skill and determination, his fine example inspiring those under his command.’ In 1916 he was promoted to Captain at the age of just 23.

Writing home

Douglas Graham Moncrieff Wright wrote home to his parents almost every day of the war. His letters are often short and give little hint of the hardships of life at the front. They usually contain a brief weather report and requests for items such as food, socks and writing paper. In a letter to his parents dated 16th January 1918, he wrote,

My darling Mother & Father,

Thanks very much for your letters, the kippers & butter. The butter is very good. I like it so much.

It came in very handy. I have got a nice billet & am very comfortable.

The weather is very changeable.

With much love from,

Douglas

The British Government was acutely aware of the importance of communication with home to boost the soldiers’ morale but also to maintain support from the home front. Over 12 million letters and 1 million parcels were sent to soldiers at the front every week for the duration of the First World War. A letter from home reached the front within 2 days of being sent, meaning that it was possible to send perishable foodstuffs such as kippers!

Souvenirs

By 1918 Moncrieff Wright was serving on the staff of the 33rd Division. In January 1918 he sent home German shoulder straps or epaulettes (schulterklappen in German) to his mother in Perth as souvenirs. Epaulettes, cap badges and letters could all betray the identification of a regiment or unit therefore such items were removed from the dead or prisoners of war. Collecting such items as souvenirs was commonplace amongst many soldiers, both British and German. It is most likely that these insignia were sent to the 33rd Division’s HQ for identification and once their purpose was served Moncrieff Wright kept them as mementoes.

The epaulette with the red ‘A’ and crown is from a soldier who served with the 117th Grand Ducal Hessian Life Infantry, “Grand Duchess Alice,” 25th Division. The ‘468’ is from the Infanterie-Regiment 468 and the ‘99’ is a 1915-pattern for the 2nd Oberrheinisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.99.

Life after the First World War

After the First World War Moncrieff Wright served with the 2nd Battalion in India and retired in 1930 with the rank of Major. In April 1928 he married Henrietta Doreen St. John in Bombay, India. They had four children; John Graham Wright, Charles St. John Graham Wright, Alice Rosemary Graham Wright and Dora Heather Graham Wright. John and Charles would both go on to have successful careers in the military.

With the Second World War approaching, Moncrieff Wright returned to The Cameronians and in June 1939 was gazetted to Lieutenant Colonel with the 6th Battalion. He then commanded the 10th Battalion from 1939 until 1942, and thereafter held positions on the staff of the Home Guard until his retirement in 1945.

Life Outwith the Army

Lt. Col Moncrieff Wright led a full and active life. He became a J.P. for Perthshire in 1933 and was appointed as the Deputy Lieutenant of Sutherland in 1946 (a Lord Lieutenant is appointed by the Crown to act as one of the monarch’s representatives in Scotland). He was a renowned hunter and took part in big-game shoots while in India. He was also experienced in salmon fishing and deer stalking. As a result of his expertise he was elected as a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society in 1926. He was also Chairman of the Scottish branch of the British Field Sports Society from 1952 to 1960.

He died on 1st May 1983, aged 89.

Acknowledgments

I am greatly indebted to members of the Great War Forum for their valuable information and identification of German regiments.

The epaulettes currently feature as our ‘Curator’s Choice’ and can be seen on display at Low Parks Museum, Hamilton. They will be displayed at Hamilton Townhouse Library, Rutherglen Library and Lanark Library over the next few months.

Comments:

Cameronians in the First World War – new display at Low Parks Museum

We have recently changed over our temporary display case at Low Parks Museum based on The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in the First World War. The new material focuses on the Gallipoli campaign and the Battle of Loos, in which several battalions of The Cameronians were engaged.

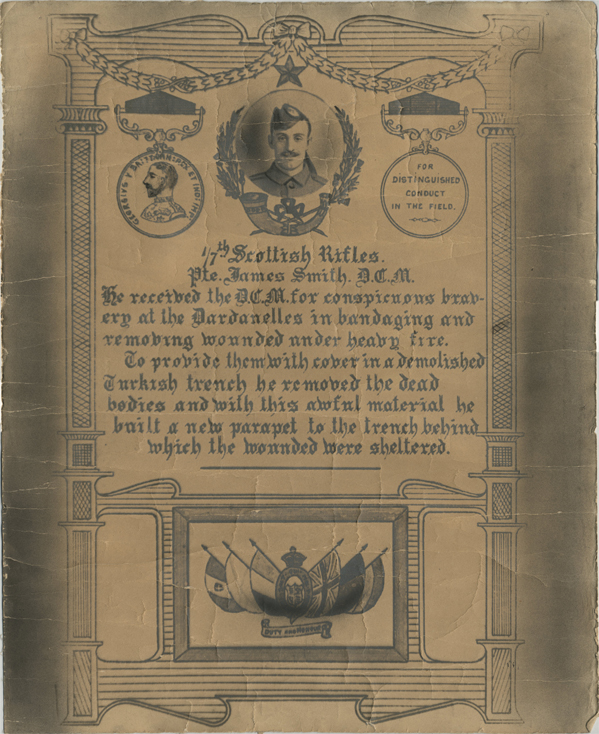

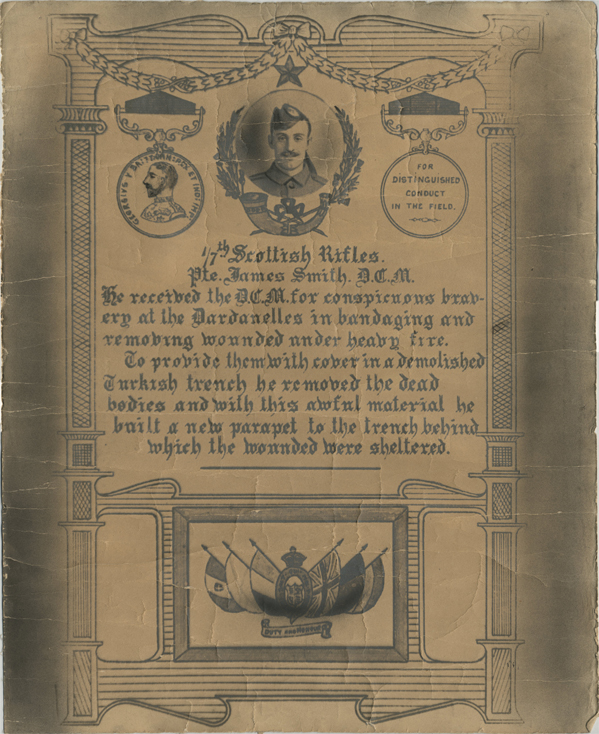

One item on display is the Distinguished Conduct Medal awarded to Private James Smith of the 7th Scottish Rifles. Private Smith was given the award for his bravery in assisting soldiers who had been wounded in an attack launched on 12th July 1915. This certificate from the museum collection describes Private Smith’s actions that day.

Certificate describing the events of 12th July 1915, that led to Private Smith being awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal

Also on display is the battered old bugle carried throughout the War by the bugler of the 10th Battalion Scottish Rifles. The 10th Scottish Rifles arrived in France on 10th July 1915, as part of the 15th Scottish Division. Their first major action was at Loos on 25th September 1915, where they suffered heavy casualties in the attack on Loos village and the subsequent action on Hill 70. When the War had ended the bugle was presented to Colonel A. V. Ussher, the officer who had commanded the Battalion at the Battle of Loos, and where he himself had been badly wounded.

Bugle carried by the bugler of the 10th Scottish Rifles throughout the First World War

You can see these, and many more objects from the regimental collections of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), on display at Low Parks Museum, Hamilton.

Remember, you can also search and browse thousands of objects from the museum collection using our online collections website:

http://www.sllcmuseumscollections.co.uk/online_collection.jsp

Comments:

Remember Gallipoli

Sunday 28th June 2015 marks the 100th anniversary of one of the blackest days in the history of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). It was on that fateful day in 1915 that both the 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles attacked the Turkish trenches at Gully Ravine on the Gallipoli peninsula. The combined losses of the two battalions for that single day would never be equaled by the Regiment on any other day of the entire First World War. With this in mind it is rather unfortunate that the significance of the Gallipoli campaign has been largely forgotten, particularly in Scotland.

Both the 7th and 8th Battalions were Territorial Force battalions of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). Both battalions were based in Glasgow; the 7th Scottish Rifles had its headquarters at the old 3rd Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteer drill hall on the corner of Copelaw Street and Victoria Road (the building remains to this day), while the 8th Scottish Rifles were based out of the drill hall on Cathedral Street, now part of the grounds of the University of Strathclyde. Most of the officers and soldiers of these battalions were Glasgow-men, living and working in the city and the surrounding area. As Territorial soldiers they would regularly meet at headquarters for drill, and attend yearly camps where they would take part in field training and musketry practise.

Men of the 7th Scottish Rifles at a pre-war Camp

The Territorial Force wasn’t ever intended to be used as part of an Expeditionary Force abroad; in the event of a large war these soldiers were to be used for home defence, freeing up regular battalions to take the fight to the enemy. By the end of 1914 the situation had changed and several Territorial battalions (including the 5th Scottish Rifles) were already fighting on the Western Front. So it was that the 52nd Lowland Division (comprised entirely of Scottish Territorial soldiers) found itself en route to Gallipoli towards the end of May 1915.

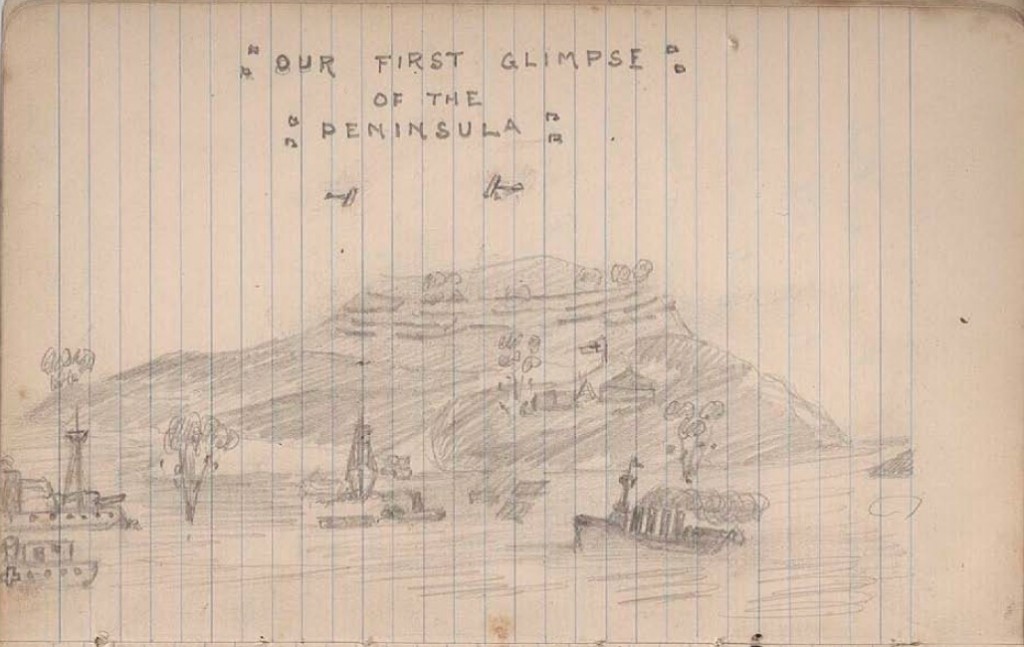

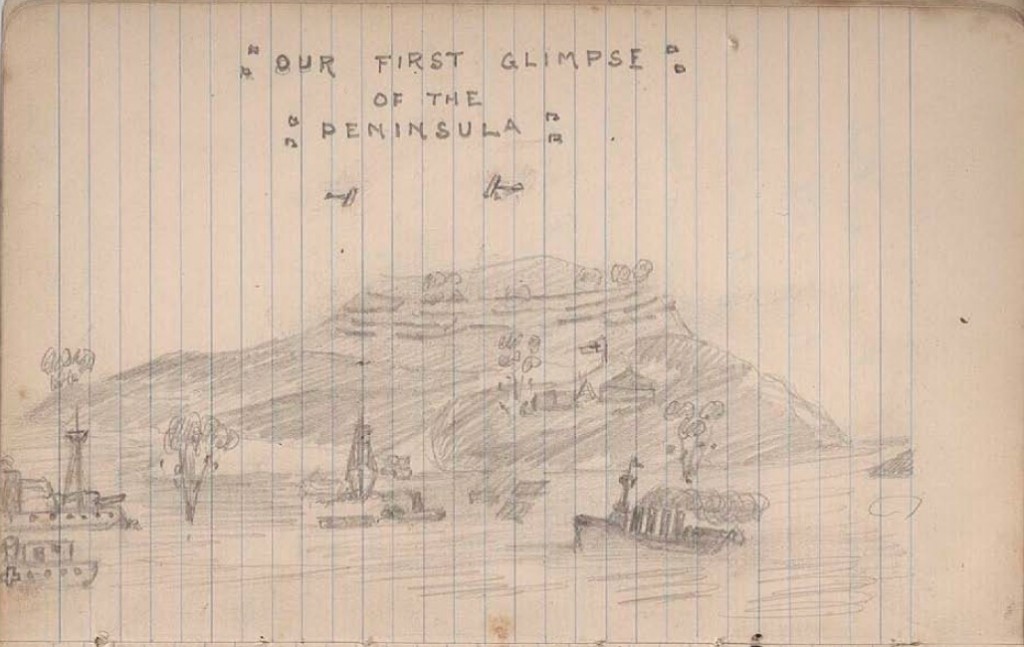

‘Our First Glimpse of the Peninsula’ by Private C. R. Bow, 7th Scottish Rifles

The 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles formed part of the 156th Brigade of the 52nd Lowland Division; both battalions landing at Cape Helles, Gallipoli, on 14th June 1915. The very next day they suffered their first casualties as a result of shelling from Turkish heavy guns, and from sniper and rifle fire. On 21st June the 8th Battalion suffered a heavy blow when their Commanding Officer, Colonel H. M. Hannan, was killed by a sniper.

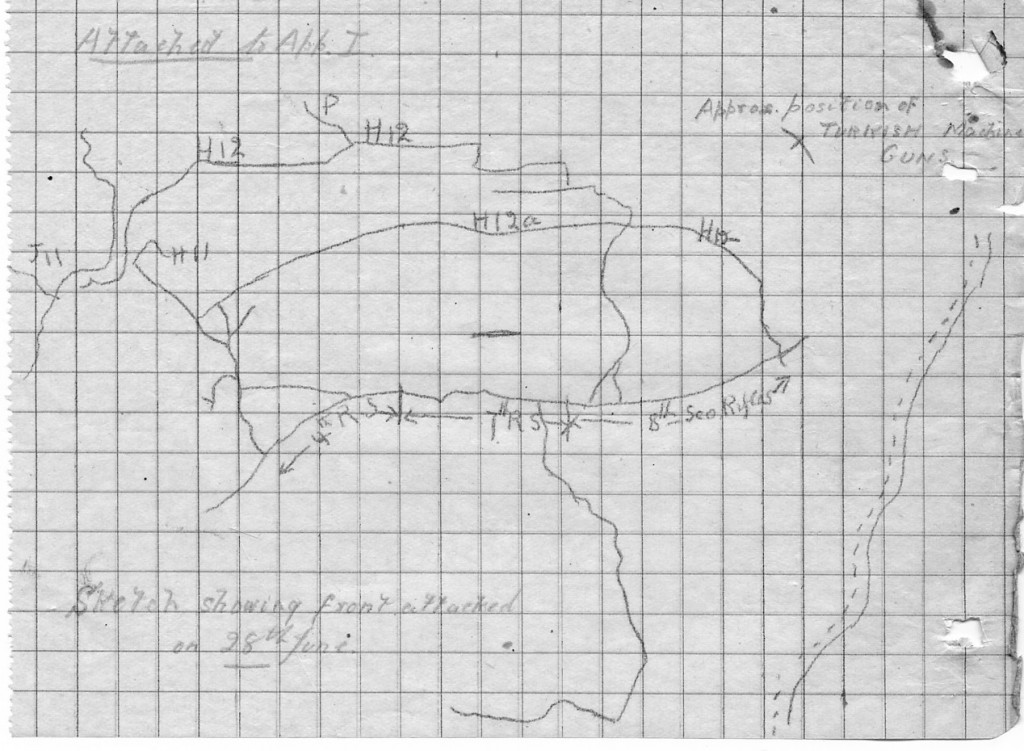

On 27th June, orders were received for a large scale attack the next day. The 156th Brigade would form the right-flank of the attacking force; the 8th Scottish Rifles were to be one of the battalions in the initial assault, with the 7th Scottish Rifles close behind as Brigade reserve. The attack was to be preceeded by a short artillery bombardment of the Turkish defences. Unfortunately for the men of the Scottish Rifles, and unbeknown to them at the time, there would be no bombardment of the trenches they were tasked to capture.

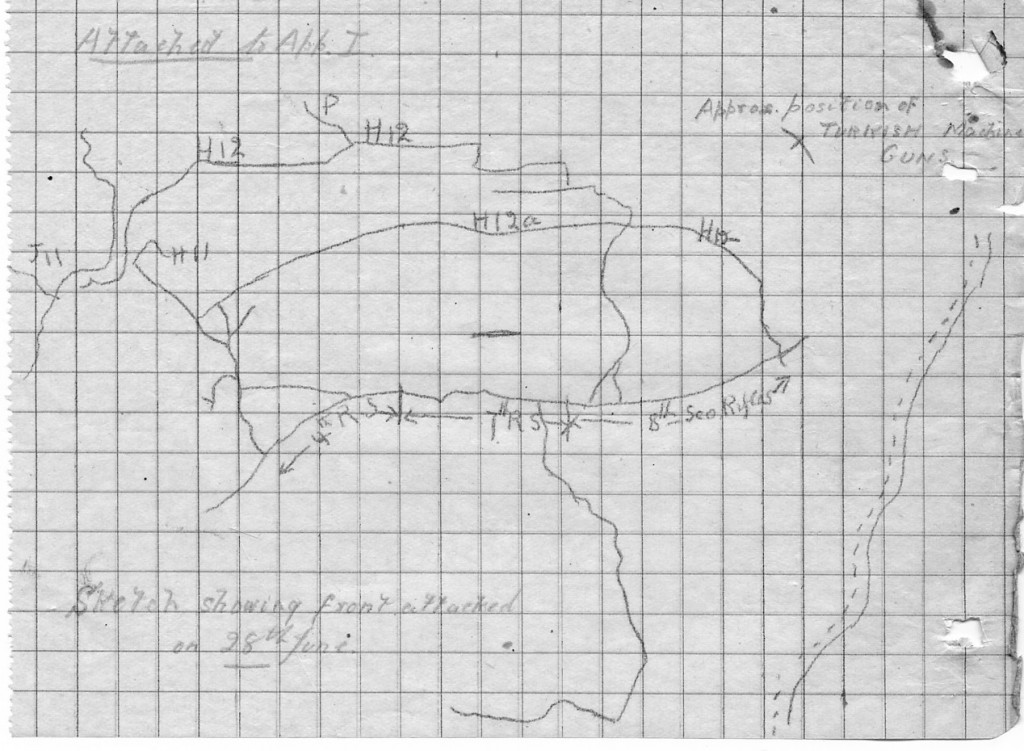

Sketch map showing the area attacked by 156th Brigade on 28th June.

Major J. M. Findlay, who had taken command of the 8th Battalion on the death of Colonel Hannan, described the attack:

Prompt at 1100 the whistles blew, and up and over went Nos. 1 and 3 Companies, followed almost immediately by No.2 Company. Five minutes after they had started they were practically wiped out, and No. 4 Company from the support trench had also suffered severely even before they reached our front trench…there was a ridge running between our line and the Turks’ front line, having crossed which every advancing man was subjected to a deadly fire from right, front, and left, and it was when each successive wave advancing topped this rise that line after line was enfiladed and mown down. Very few men reached the Turkish trenches, and those who did were either killed or wounded, with the exception of one or two men who managed to crawl back to our trenches during the night.

Many of the casualties suffered that day were caused by a Turkish machine gun, sited on the extreme right of the 156th Brigade’s advance. The lack of artillery support on this side of the attack was telling; had the machine gun been knocked out before the men advanced they might well have taken the Turkish trench and with lighter casualties.

Shortly after the 8th Battalion’s attack was stalled by the heavy fire laid down by the Turkish defenders, Major Findlay led a support group to try and gather up survivors and lead them on. This group made it to within around 50 yards of the Turkish trench when Findlay was also hit, shot through the neck. Amazingly, Findlay survived. Captain Bramwell, the adjutant, was not so lucky – he was killed by Findlay’s side – nor was 23 year-old Lieutenant Stout, the signalling officer, who was killed by a shell splinter as he tried to drag Major Findlay to safety.

Major Findlay, Colonel Hannan, Captain Bramwell

Lieutenant Stout

There was no shortage of bravery that day. When it was discovered that one of the few surviving officers of the 8th Scottish Rifles, Lieutenant Tillie, was lying wounded out towards the Turkish lines, Sergeant Miller risked his own life to save him. He succeeded in bringing the wounded officer back to the British trenches. Sergeant Miller never received any gallantry medals for his actions that day, but after the War Lieutenant Tillie did present him with a handsome pocket watch as thanks for saving his life that day.

Pocket watch presented to Sgt. Miller

Inscription inside the pocket watch

The 7th Scottish Rifles, who were in reserve when the attack started, were soon sent forward to reinforce the assulting force. They too were caught up in the heavy rifle and machine gun fire laid down by the Turkish defenders. While their casualties were not quite so high as the 8th Battalion, they too were badly mauled in the attack. The Commanding Officer of the 7th Scottish Rifles, Colonel Boyd-Wilson, was killed while leading the battalion forward. Many more officers were killed and wounded, command falling onto junior officers and sergeants. The Turkish line was taken in places, but enemy reinforcements made it almost impossible to consolidate any gains that had been made.

At one point in the action a Turkish grenade fell into a section of trench packed full of men of the 7th Scottish Rifles. Lance Corporal Ross and Private Young, realising the devastation the grenade would cause in such a confined space occupied by their comrades, tried to stifle the effects of the blast. Lance Corporal Ross put his foot on the grenade while Private Young bundled up a greatcoat and held it over the grenade with his hands and body. The grenade exploded, badly injuring the two men, but saving their comrades from harm. For their actions both Lance Corporal Ross and Private Young were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

In the early hours of 29th June, the survivors of the 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles were relieved and withdrawn to the reserve lines. The next day was spent trying to clear as many wounded and dead from the front line trenches as was possible. It was then that the enormity of the losses sustained by the two battalions became apparant. A roll call on 30th June revealed that the 7th Scottish Rifles had lost 14 Officers and 158 Other Ranks killed or missing, with a further 104 men of all ranks being wounded. The 8th Scottish Rifles had sustained terrible losses – 15 Officers and 334 Other Ranks killed or missing, and 124 men of all ranks wounded. The majority of those reported as missing were never seen again, most likely killed or having died of wounds. Among those killed was a young Private called John Gray of the 7th Scottish Rifles. The day before the attack he had written to his mother in Glasgow; it would ultimately be his last letter home:

…Well Mother about myself, I’m keeping A1 now, and pushing through this life as best I can. It’s not a pleasant one, but it’s got to be done. Things have been very quiet here lately, but as the saying goes “there’s always a calm before a storm.” We’ve been resting now since Thursday, so that I think we’ll be going back to the trenches tonight. Well Mother, as there’s nothing more to say at present Ill start summing up, give my best love to Liz and all at home, and tell all my friends I was asking for them… I’ll draw to a close now, with the hope that it won’t be many weeks or months before we’re sailing back to Bonnie Scotland.

The next time one hears the name ‘Gallipoli’ spare a thought for the thousands of soldiers from all countries who fought and died there in the First World War, and remember the hundreds of men of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) who fell at Gully Ravine.

Comments:

Log in