For Bravery in the Field – 21st to 24th December 1917

100 years ago today, on 21st December 1917, a four-man patrol from the 10th Scottish Rifles left the relative safety of their trenches and crept in to no man’s land. Their objective was to establish the condition of the enemy’s defenses, and to try and establish the identity of the German unit defending them. It wasn’t until three days later, on Christmas Eve 1917, that two of the patrol would drag themselves back into the British lines – wounded, dehydrated, and suffering from exposure and frost-bite – while the other two members were presumed dead.

The two men who made it back to the British trenches on 24th December 1917 were Sergeant John Wilson, and Lance Corporal John Thomson. Both men were awarded the Military Medal for their actions on the patrol, but within a few days Lance Corporal Thomson had succumbed to his wounds, and Sergeant Wilson would ultimately have both his legs amputated as a result of wounds exacerbated by frost-bite.

Military Medal of Sergeant John Wilson, on display in Low Parks Museum (obverse – left, reverse – right)

The patrol that set-out on 21st December 1917 comprised of four men; Second Lieutenant Ewen, Sergeant Wilson, Lance Corporal Thomson, and Private Aberdeen. Sergeant Wilson had led a similar patrol on the previous evening when a German post was encountered, but this was too well defended for them to try and rush in an effort to secure prisoners.

The patrol came up to what they thought was the German lines, but which actually turned out to be a small section of abandoned trench that the German forces were using as an observation and listening post. The lone German sentry was successfully captured by the patrol and while returning to their own lines they encountered and were attacked by a German patrol comprising of between 12 and 15 men. In the ensuing fight, the German prisoner was killed, and all four men of the British patrol became casualties. Lieutenant Ewen was thought to have been killed outright, and Private Aberdeen was badly wounded. Wilson and Thomson, both wounded, were able to get away, using the myriad of shell-holes as cover. Looking back, they saw the forms of Lieutenant Ewen and Private Aberdeen being dragged away towards the German lines.

Using the cover of darkness, Wilson and Thomson dragged themselves to what they thought was the British lines, only to find they had lost their way in the confusion of no man’s land and were actually near the parapet of the German trenches. It took them almost three days to make their way back to the British lines, as by this time Thomson was almost incapacitated through blood loss and the effects of exposure and Wilson had to physically drag him, even although he himself was wounded and suffering from frost-bite. Having survived all this, the unfortunate pair were almost met with the cruel fate of being killed by their own men, as when they first reached the British lines they were fired upon by the wary soldiers manning the trenches. On Christmas Eve they met a British patrol who assisted them back to the 10th Battalion’s lines.

The fate of Lieutenant Ewen and Private Aberdeen would not be known by the Battalion for some time. Wilson and Thomson had assumed Lieutenant Ewen killed in the fighting against the German patrol. He had in fact been wounded and taken prisoner. He recovered from his wounds, although he spent the remainder of the War as a prisoner in Germany. Ewen was a chemist and druggist in Aberdeen in civilian life; he had originally served as a private soldier in the Royal Army Medical Corps before being granted his commission and had only been serving with the 10th Scottish Rifles for a short time before commanding the fateful patrol.

Private Archibald Aberdeen was also wounded and taken prisoner. He succumbed to his wounds and died the next day, on 22nd December 1917. Private Aberdeen was buried by his German captors in a French cemetery behind their lines. In 1924, Private Aberdeen’s remains were reburied by the Imperial War Graves Commission in Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery among his comrades who died in the War.

Wilson and Thomson were awarded their Military Medals on 1st January 1918. Three days later, on 4th January, Lance Corporal John Barr Thomson died of his wounds and the hardships suffered during his ordeal in no man’s land. John Thomson was from Hamilton, Scotland, and was 38 years old at the time of his death. He is buried in Etaples Military Cemetery.

Sergeant John Wilson was also from Hamilton. He had joined the 6th Scottish Rifles, the local Territorial Force Battalion of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1912. John was a compositor with his local newspaper, The Hamilton Advertiser. Embodied for active service when war was declared in August 1914, John first went to France with the 6th Scottish Rifles in March 1915. Like Lieutenant Ewen, Sergeant Wilson was only transferred to the 10th Scottish Rifles a few months before he took part in the patrol. He had already been wounded in action, and had also served for a short time with an Officer Cadet School where he was considered for training as an officer. During the December patrol described above, Wilson had suffered a gun shot wound to the left thigh. In addition he suffered severe frost-bite as result of spending so long in wet, freezing conditions. The damage to his legs was severe enough to result in him having both legs amputated, and he was discharged from the army on medical grounds in April 1918, aged 24.

Sergeant John Wilson’s Military Medal is on display in Low Parks Museum, in his native Hamilton.

Comments:

How Many Were Left?

After three years of bloody conflict, the First World War on the Western Front again settled into stalemate in the Winter of 1917-1918. As the new year dawned the British offensives at Arras, Ypres, and Cambrai were memories. All eyes now turned to the German offensive all ranks knew was coming. Given the costly fighting of the previous years one would not expect to see veterans of Loos or the Somme still manning front line trenches and preparing for the impending battle. Yet hidden in the war diary of the 9th Scottish Rifles for 4 February, 1918, lies a glimpse inside the makeup of the men who’d fight in the coming year of victory.

NCOs of C Coy, 9th The Cameronians S.R. Feb 1919, Germany – TNB or Thomas Nicholson Banks is identified in the 2nd row – belonged to Thomas Nicholson Banks who served with the 9th Bn The Cameronians S.R. The building in the background is Schloss Benrath, near Dusseldorf.

On that date the 9th Scottish Rifles were in rest billets in the French town of Vaux-Sur-Somme. They paraded in the morning in front of the Commanding Officers of their 9th (Scottish Division) and 27th (Lowland) Brigade. A group of the men were presented medal ribbons. In total the Cameronians of the 9th received:

Military Cross 2.

Bar to Military Medal. 1.

Military Medals. 14.

1914 ‘Star’. 49.

Belgian Croix de Guerre. 3.

49 men were left. 49 of those who had left Hamilton barracks in 1914 as part of Kitchener’s Army, one of the Glasgow or Lanarkshire territorial battalions, or of the two regular battalions who served in France in 1914-15. The 1914 Star was awarded in the Winter of 1917-1918 to those who had served overseas in 1914-15, and the amount awarded to members of the 9th Scottish Rifles gives s a glimpse of the experiences of the battalion, both through the few who remained, and the length of time those 49 had spent at the front with the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) or their original units. There was still another year left to fight, and there would be thousands more men lost until the Armistice the following November. The 9th Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) would be at the forefront fighting during the Spring Offensive, at Mt. Kemmel south of Ypres as part of the Battle of the Lys, and the advance to victory.

1914 Star Medal with bar: 5th Aug to 22nd Nov 1914. Awarded to 9804 Frederick Anderson 1/Scot Rif.

Comments:

Posted: 08/12/2017 by JamesTaub in First World War

A Cameronian View of Passchendaele

With the centenary of the Third Battle of Ypres drawing to a close, let us look back on the activities of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in this infamous battle.

In actuality, the Third Battle of Ypres was divided into several smaller battles which took place throughout the Ypres Salient from 31 July to 10 November 1917. Battalions of the regiment were present at almost every single one of these smaller engagements. Starting on 31 July, the 10th Battalion with the 15th Scottish Division attacked German positions around Beck House on the Frezenberg Ridge. It’s four companies were divided up between various battalions of the Division as extra strength to assist in their various objectives. Simultaneously the 2nd Battalion with the 8th Division attacked along the banks of the Hanebeek.

Both the 2nd and 10th Scottish Rifles would return to the fight on 16 August, and both in relatively the same positions they had fought in in late July and early August. The 10th would assault positions such as Gallipoli Farm, Iberian Farm, and Beck House. The 2nd again attempted a crossing of the Henebeek and again suffered heavily casualties being bogged down in the mud.

On 20 September the 9th Scottish Rifles entered the battle with the 9th (Scottish) Division, assaulting the Frezenberg Redoubt. (Now the site of the Scottish Memorial.) This was the British Army’s first attempt to counter the new German defense in depth tactics which had stymied their advances earlier in August. The weather however, was beggining to interfere with any further pushes. As the 9th’s After Action Report records the effect on weapons:

Breech and Muzzle Covers were used by all except first waves, but still rifles were difficult to keep clean, and at Final Objective a great many were caked with mud, and, in a few instances, unserviceable. The need for cleaning rifles at earliest opportunity after objective is reached ought to be impressed on all ranks during training.

The Scottish Memorial, Frezenberg. Site of the 9th Scottish Rifles’ action in August, 1917.

By 26 September the 1st and 5/6th Battalions had arrived as part of the 33rd Division. They pushed up the Menin Road and through the South East corner of the now infamous Polygon Wood. Company Sergeant Major Docherty of the 5/6th Battalion noted the confusion of the fighting in a later issue of The Covenantor:

We went through and beyond the pill boxes and lay down; the shell craters in this area had to be seen to be believed. Serjeant Hay and I went along the line to get the men straightened out; dawn had broken by this time and men of the Suffolks and B and C Companies were all mixed up. The shelling was so bad on both sides and the confusion such that some of our men were digging in facing the direction from which our own artillery was firing.

The two battalions of the Cameronians with the rest of the 33rd Division successfully assisted the Australian attack which captured Polygon Wood. Though this was not without large losses to both sides.

Fighting continued into October with the 9th Battalion returning to attack a position near Kronprinz Farm. By 10 November the Canadians had captured Passchendaele Ridge, with the now destroyed village resting on top. They were relieved by units which included the 1st and 5/6th Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). The 5/6th took up position around a block house known as Tyne Cot. There the began to bury their own dead, as well as scattered dead from other regiments. Their War Diary reads

The beginning of a cemetery the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) laid down grew into the famous

Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing, the largest British and Commonwealth military cemetery in the world. Following the fighting the regiment settled down to endure the cold and trench warfare of the Winter of 1917-18. To come in the Spring was the great German offensives, and the war still had one full year to go.

Comments:

Posted: 29/10/2017 by JamesTaub in First World War

“For Services Rendered…” 31st July 1917

Today marks the anniversary of the opening of the Third Battle of Ypres, 31st July 1917, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele. This was the start of a British-led campaign that would continue into November of that year, and result in almost half a million casualties from both sides. Even at the time, the decision to launch the offensive met with controversy, and its objectives, successes and failures are subjects that will continue to be debated for many years to come. While the merits of this particular campaign, and indeed the events and circumstances surrounding the First World War itself, are continuingly being scrutinised, these anniversaries can provide an opportunity to look back and take a moment to remember the individuals who took part.

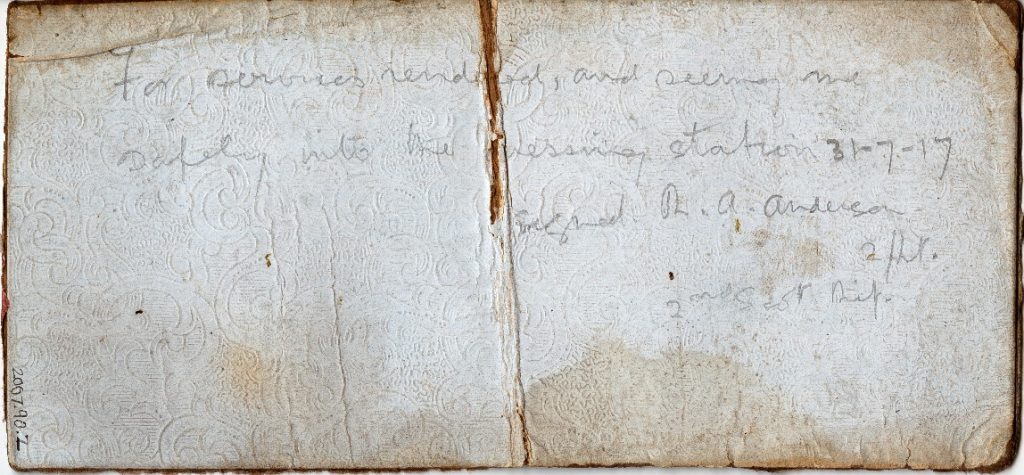

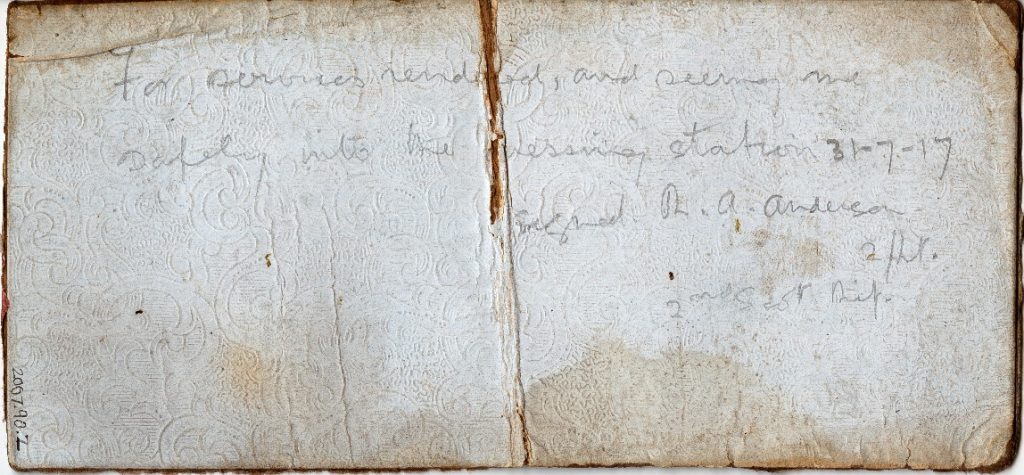

This fragment of a cigarette packet is probably one of the smaller, more fragile objects that make up The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) regimental museum collection. It is the type of thing that, under normal circumstances, might have easily been discarded by its owner without much thought. So why should such an item have been kept, and ultimately deposited in a museum? A look at the scribbled message on the reverse of the packet reveals the significance of such an everyday item.

The message reads: “For services rendered, and seeing me safely into the dressing station 31-7-17, signed R. A. Anderson, 2/Lt, 2nd Scot. Rif.”

This was the dictated message from 2nd Lieutenant Roderick Andrew Anderson, of the 2nd Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), to Private George Gould from Edinburgh. Lieutenant Anderson was just one of many of the 2nd Scottish Rifles who was wounded on 31st July 1917, and Private Gould was the man who helped the wounded officer to the Battalion dressing station, quite possibly saving his life. The men were of similar age, around 20 years old. Anderson’s wounds were serious enough that he was evacuated from the Front, and he would not return to the 2nd Battalion until 25th June 1918, almost a year later. Before leaving the Battalion area, Anderson asks for the above message to be written on his cigarette packet, and that it be passed to Private Gould as a small token of his thanks. Whether Private Gould was a smoker or not, we do not know. Perhaps he shared the cigarettes with his friends, or traded them for sweets or other useful items. What we do know is that he kept the packet with its message of thanks until the day he died. George Gould was killed on 6th January 1918, still serving with the 2nd Scottish Rifles. The cigarette packet was returned to his family with his personal effects; years later it, along with some photographs and his Memorial Death Plaque, was donated to the regimental museum collection.

Private George Gould

This photograph of George was probably taken during a visit home. It was taken at Colin Campbell’s studio on 39 South Bridge, Edinburgh, not far from where George and his family lived, at number 63. The gold stripe worn on his lower left sleeve indicates he had been wounded on service. George had been recorded in a list of wounded soldiers sent to Stobhill Hospital on 8th May 1916, published in The Scotsman newspaper. At the time, George was serving with the 1st Battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers – he subsequently transferred to the 2nd Scottish Rifles. The Wound Stripe alone is evidence that George had served at the Front by the time this photograph was taken. The patch worn on the right sleeve, below the shoulder seam, is that of the 8th Division, in which the 2nd Scottish Rifles served for most of the War’s duration. You can see an original example of this badge on our Online Collections browser – http://www.sllcmuseumscollections.co.uk/search.do?id=147158&db=object&page=1&view=detail

By the time Roderick Anderson returned to the 2nd Scottish Rifles, George had been killed and buried in Passchendaele New British Cemetery. Anderson would survive the First World War, finishing the War with the rank of Captain. In June 1919 he was awarded the Military Cross for his services in the First World War – the original citation for which reads:

“This officer has served with the Bttn since 1916 except when he was wounded. He took part in many engagements as a platoon commander and in the Battle of Ypres 31/7/1917 led his platoon with skill and determination. He takes a keen cheerful and intelligent interest in his work and has been at all times a conscientious hard working officer. Lately he has been performing the duties of Asst. Adjutant during whose absence he has done his work with considerable credit, both in action and out of the line. He is an exceptionally keen soldier.”

Roderick remained in The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) after the First World War, serving with the 2nd Battalion in India and Kurdistan. He married in 1931, and had two children. In April 1935, Roderick resigned his commission from the British Army; he returned to his native New Zealand with his family to work in his father’s engineering business. Civilian employment didn’t quite agree with Roderick, and he joined the Royal New Zealand Air Force in 1937. During the Second World War, Roderick volunteered to serve once again with The Cameronians, and he duly joined the 1st Battalion in 1941, serving with them in Burma. He was wounded near Pegu in March 1942, by which point his age and the physically gruelling conditions of active service were taking it’s toll. He was posted to a Staff position and remained in service until the end of the Second World War, retiring with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Roderick’s health never quite recovered from his service in the Second World War, and he died in 1958 aged 60. Brigadier W. B. Thomas, an old comrade of Roderick’s since the two were at Sandhurst together in 1915, wrote of him:

“Roderick Anderson and I joined the Regiment from Sandhurst on the same day in April, 1916. We served together almost continuously until he retired and went to New Zealand in 1935. As he was employed with the New Zealand Air Force he need not have come back during the war, but such was his love for the Regiment that he was determined to serve with it. He rejoined the 1st Battalion in Secunderabad in 1941. Unfortunately there was not time for him to get as fit as the rest of us before he went to Burma. The arduous retreat inflicted a strain on his health from which he never fully recovered. Nethertheless he always pulled his weight and set an inspiring example. He was a wonderful friend and companion.”

Roderick Andrew Anderson, seated cross-legged, right of front row. This photograph was taken shortly after the Armistice in November 1918, and shows Officers, Warrant Officers and Non Commissioned Officers of the 2nd Scottish Rifles.

The War Diary for the 2nd Scottish Rifles records that 38 officers and men of the Battalion were killed on 31st July 1917, and a further 146 wounded, while 19 men were reported missing in action. Roderick Anderson was among those wounded; perhaps his fate might have been different had it not been for George Gould.

Comments:

Why we remember

Tomorrow is Friday 11th November – the 98th anniversary of the signing of the Armistice concluding the hostilities of the First World War. At 11am tomorrow morning, people all over the country will stop what they are doing to observe the anniversary in a moment of silent reflection. On Sunday 13th, Remembrance Sunday, services will be held nationwide to commemorate those who died in conflict, past and present.

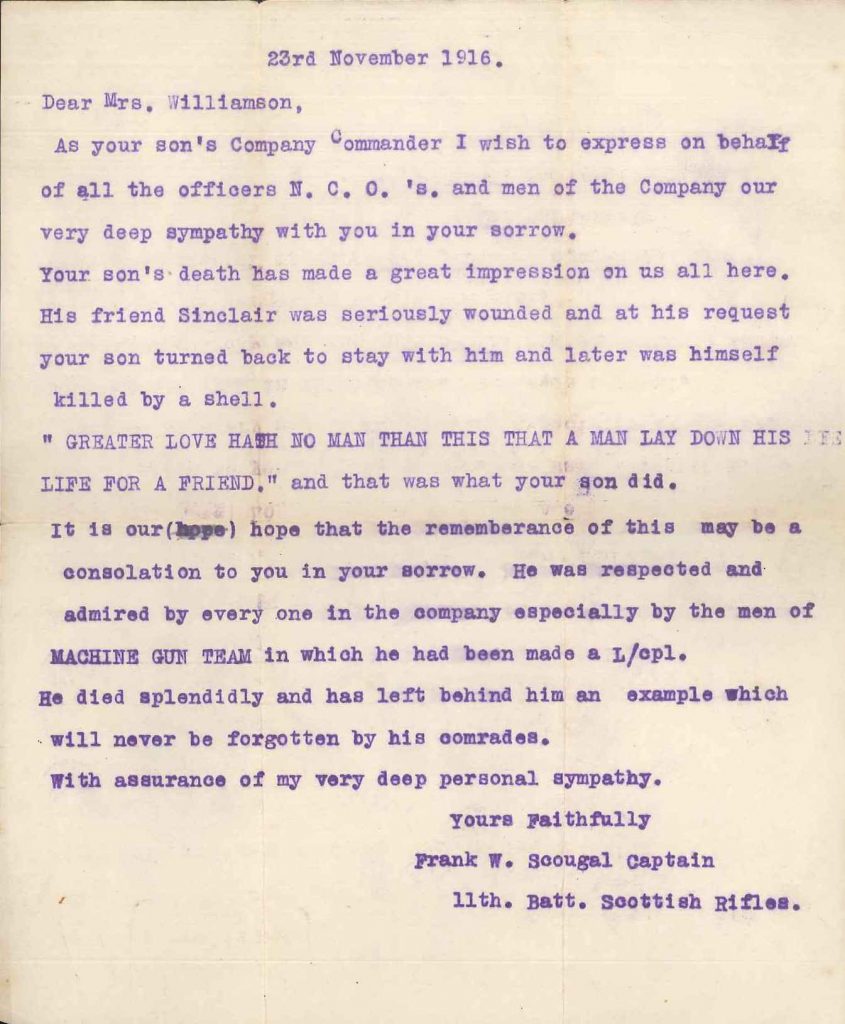

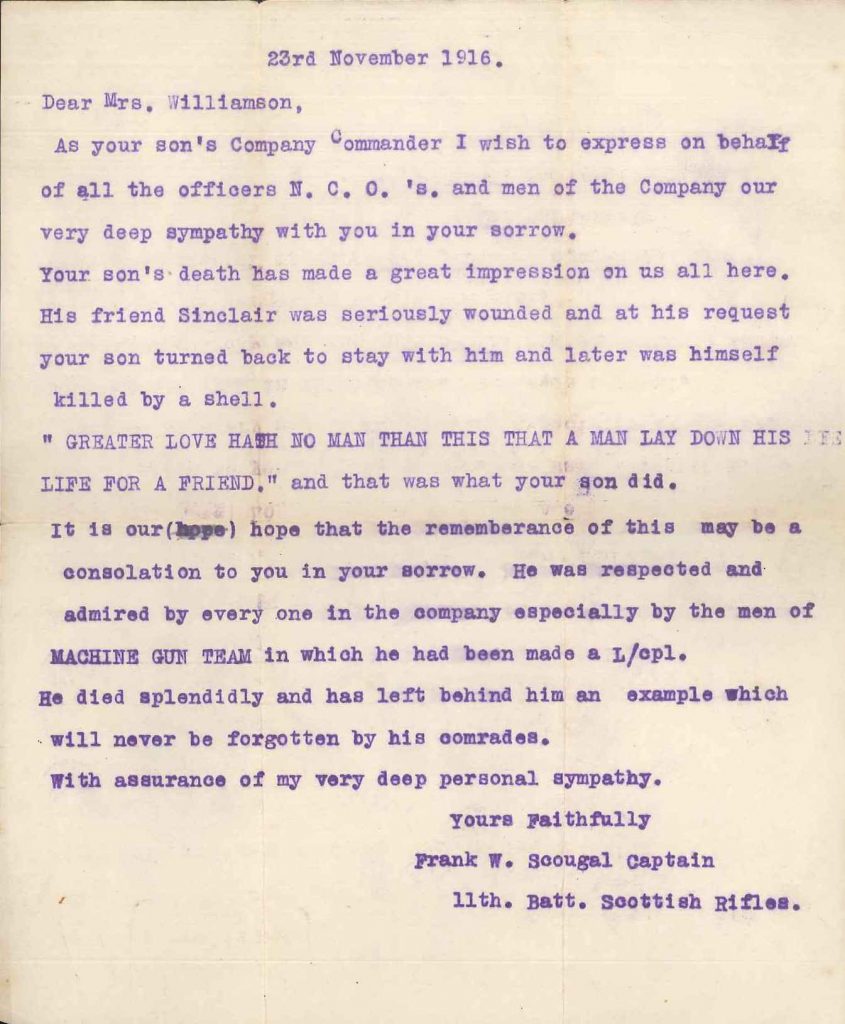

Many of the Remembrance events that will take place over the weekend will be centred around the First World War, and in particular the Battle of the Somme which ran from 1st July to 18th November 1916. Of course, the fighting in 1916 was not confined exclusively to the Somme region, nor indeed to the Western Front. This letter from the museum collection reminds us that the First World War was indeed a global conflict, and reminds us of the loss and sacrifice that comes with War.

The letter was written to the mother of William Williamson, who was killed on 19th November 1916, by the officer commanding William’s company, Captain Frank Scougal. William was part of the 11th Scottish Rifles – a battalion of Kitchener’s Army serving at that time in Salonika, now part of Greece. In the letter, Captain Scougal explains that William died while trying to assist a friend, Sinclair, who had been badly wounded. Both men were killed by shellfire and were buried in Karasouli Military Cemetery.

Sadly, Frank Scougal did not survive the War; he was killed on 19th September 1918, just weeks before the signing of the Armistice. Tragically, Frank’s younger brother, Alec, had been killed the day before while serving on the Western Front. It is testament to the scale of the loss witnessed in the First World War that one short letter can come to represent the grief suffered by so many families.

Comments:

Log in