ID’ing Your Cameronian 1914-18

One of the identifying features of a British soldier is the various insignia and trappings of their regiment. The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) are no exception to this. On service during the First World War, members of the regiment wore a uniform and used kit the same as other soldiers of the British Army, yet as we’ll see they retained certain regimental distinctions which can help you identify a Cameronian in a crowd.

4th Army School in France. Can you tell which one of these soldiers is a Cameronian? (Photo Courtesy of James Taub)

THE UNIFORM

Like other soldiers of the British Army when in the field the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) wore a khaki coloured wool uniform. Officially referred to as the 1907 Service Dress uniform. It consisted of trousers and a tunic. The tunic includes much of what you need to identify a Great War serviceman as a member of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

Black Buttons- As a rifle regiment, the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) were allowed the distinct honour of wearing blackened horn buttons. While on their rifle green dress uniform, they would sport buttons with a horn and thistles distinct to the regiment, during the Great War the buttons worn on service dress were the standard blackened horn button issued to all rifle regiments.

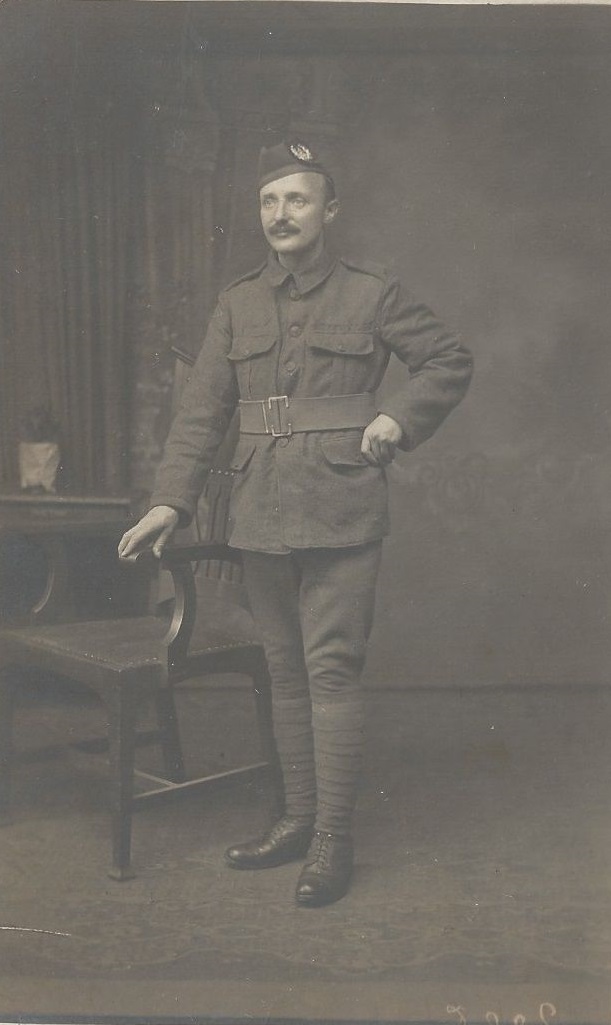

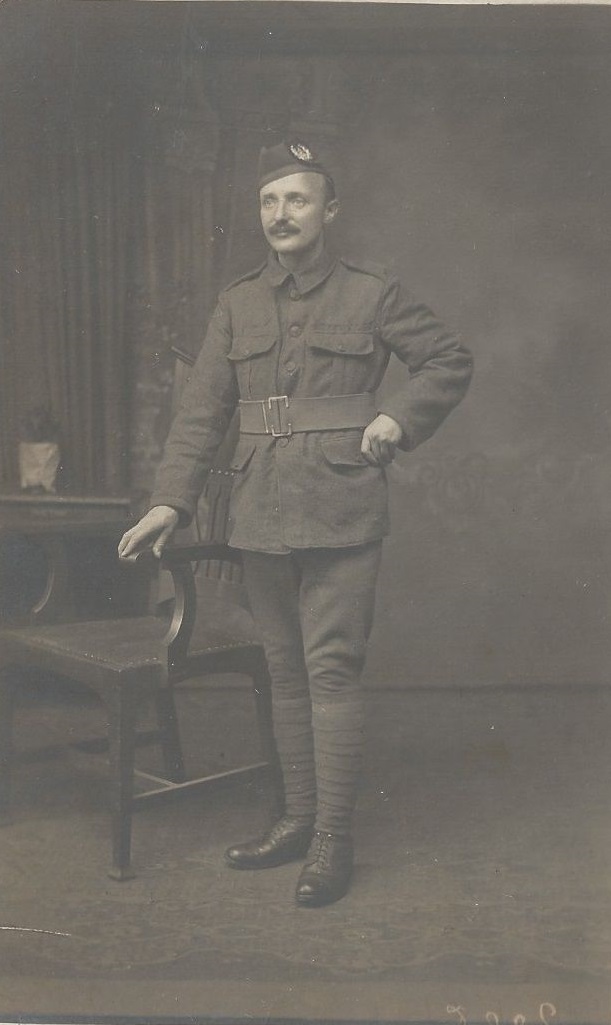

A Cameronian wearing the standard 1907 Service Dress uniform. He is sporting the regiment’s black buttons and shoulder titles. (Courtesy of James Taub)

Shoulder Titles- Although there was still conflict between the 1st and 2nd Battalions at the outbreak of the First World War regarding being called ‘Cameronians’ or ‘Scottish Rifles’, all soldiers of the regiment were issued with brass “SR” shoulder titles. These would be blackened (generally with boot polish) to acknowledge the soldier’s status as a member of a rifle regiment.

First World War SR shoulder title. (CAM 2007.39.3)

HEADWARE

The hats and helmets of the regiment would change as the war progressed. As part of the dress uniform and the initial 1914-15 uniform, soldiers would be wearing the traditional rifle green glengarry with the regimental badge. In mid-1915, a small bonnet was introduced. By early 1916 the tam o’shanter was making its appearance for wear behind the lines. Simultaneously brodie helmets were introduced for front-line wear.

Reenactors donning the glengarry, tam o’shanter, and helmet. The three main pieces of headgear for the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in the First World War.

Comments:

For Bravery in the Field – a follow up

Yesterday I wrote about the men of the 10th Scottish Rifles who went on a patrol into no man’s land on 21st December 1917. Sergeant John Wilson, from Hamilton, was one of the two men who returned to the British lines three days later, on Christmas Eve.

This morning I found some additional information that sheds some light on what happened to the brave Sergeant in the years following the First World War.

While searching through online newspaper articles, I came across an account in The Scotsman of King George and Queen Elizabeth’s Royal visit to Lanarkshire on 4th May 1938. The article recounted that, following a reception at Hamilton Town House, Their Majesties were making their way to their car when they observed in the crowd, a group of 14 men wearing medals. The King enquired who the men were, and was introduced to them by the Provost. The men were all limbless ex-servicemen from the area, and among them was none other than Sergeant John Wilson MM:

Mr Dodd [the leader of the group of ex-servicemen] drew His Majesty’s attention to John Wilson, holder of the Military Medal, who lost both his legs while serving in France. “How do you manage to get along?” inquired His Majesty, and Mr Wilson modestly replied. “Oh, fine.”

I then started looking through the regimental magazine of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), titled The Covenanter, and found an obituary notice for John Wilson, published in the January 1945 edition. It reads:

Death of Old Cameronian

We Regret to Record the death of Mr John Wilson, a linotype operator on the staff of “The Hamilton Advertiser” for over 35 years. Mr Wilson served as a non-commissioned officer in the Great War with the 6th Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He was twice wounded, once at Festubert and again in 1918 in an action in which he was awarded the Military Medal. He lost one of his fingers at Festubert. In 1918, he received a severe gunshot wound and suffered severely from frost-bite through forced to remain in “no-man’s-land” for three days. He had both legs amputated below the knee as a result of this experience. Following his discharge from the Forces, he returned to his civilian occupation and, because of his disability, was trained as a linotype operator. Even with two artificial legs he was very agile and served the firm faithfully and well up till the time of his death. There is no doubt that his general health suffered as a result of his war service, but “Jock”, as he was familiarly called, bore his illness with true Cameronian fortitude and was never heard to utter one word of complaint. Mr Wilson was one of the pioneers in the formation of Hamilton and District Branch of the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen’s Association, and was also an enthusiastic member of the Regimental Association of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). “Jock” also took a keen interest in “The Covenanter”, and in his capacity as a linotype operator he was given the job of setting-up the type for the magazine. This afforded him a great deal of pleasure and kept him very much in touch with the activities of his old Regiment. At the funeral to Bent Cemetery, Hamilton, his old Battalion was represented by the presence of its honorary colonel, Lieut. Col. J. C. E. Hay, C.B.E., M.C., T.D., D.L.

Further notifications in The Covenanter reveal that John Wilson bequeathed his medals to The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) regimental museum, and also bequeathed a sum of money to the Regimental Museum Fund.

South Lanarkshire Council’s Bereavement Services were very helpful when I made enquiries about the whereabouts of Sergeant Wilson’s grave, and armed with plot details and a map I made my way there to pay my respects. It would appear, however, that Sergeant Wilson’s grave lies unmarked; perhaps not surprising as his obituary notice made no mention of any surviving family who might have arranged a headstone. I placed a memorial cross in a tree as near as I could estimate where Sergeant Wilson’s grave might lie.

On Christmas Day, safe and warm and in the company of my family, I’ll raise a glass and spare a thought for Lieutenant Ewen, Lance Corporal Thomson, Private Aberdeen, and of course, Sergeant John Wilson, and what they went through in no man’s land 100 years ago.

Comments:

For Bravery in the Field – 21st to 24th December 1917

100 years ago today, on 21st December 1917, a four-man patrol from the 10th Scottish Rifles left the relative safety of their trenches and crept in to no man’s land. Their objective was to establish the condition of the enemy’s defenses, and to try and establish the identity of the German unit defending them. It wasn’t until three days later, on Christmas Eve 1917, that two of the patrol would drag themselves back into the British lines – wounded, dehydrated, and suffering from exposure and frost-bite – while the other two members were presumed dead.

The two men who made it back to the British trenches on 24th December 1917 were Sergeant John Wilson, and Lance Corporal John Thomson. Both men were awarded the Military Medal for their actions on the patrol, but within a few days Lance Corporal Thomson had succumbed to his wounds, and Sergeant Wilson would ultimately have both his legs amputated as a result of wounds exacerbated by frost-bite.

Military Medal of Sergeant John Wilson, on display in Low Parks Museum (obverse – left, reverse – right)

The patrol that set-out on 21st December 1917 comprised of four men; Second Lieutenant Ewen, Sergeant Wilson, Lance Corporal Thomson, and Private Aberdeen. Sergeant Wilson had led a similar patrol on the previous evening when a German post was encountered, but this was too well defended for them to try and rush in an effort to secure prisoners.

The patrol came up to what they thought was the German lines, but which actually turned out to be a small section of abandoned trench that the German forces were using as an observation and listening post. The lone German sentry was successfully captured by the patrol and while returning to their own lines they encountered and were attacked by a German patrol comprising of between 12 and 15 men. In the ensuing fight, the German prisoner was killed, and all four men of the British patrol became casualties. Lieutenant Ewen was thought to have been killed outright, and Private Aberdeen was badly wounded. Wilson and Thomson, both wounded, were able to get away, using the myriad of shell-holes as cover. Looking back, they saw the forms of Lieutenant Ewen and Private Aberdeen being dragged away towards the German lines.

Using the cover of darkness, Wilson and Thomson dragged themselves to what they thought was the British lines, only to find they had lost their way in the confusion of no man’s land and were actually near the parapet of the German trenches. It took them almost three days to make their way back to the British lines, as by this time Thomson was almost incapacitated through blood loss and the effects of exposure and Wilson had to physically drag him, even although he himself was wounded and suffering from frost-bite. Having survived all this, the unfortunate pair were almost met with the cruel fate of being killed by their own men, as when they first reached the British lines they were fired upon by the wary soldiers manning the trenches. On Christmas Eve they met a British patrol who assisted them back to the 10th Battalion’s lines.

The fate of Lieutenant Ewen and Private Aberdeen would not be known by the Battalion for some time. Wilson and Thomson had assumed Lieutenant Ewen killed in the fighting against the German patrol. He had in fact been wounded and taken prisoner. He recovered from his wounds, although he spent the remainder of the War as a prisoner in Germany. Ewen was a chemist and druggist in Aberdeen in civilian life; he had originally served as a private soldier in the Royal Army Medical Corps before being granted his commission and had only been serving with the 10th Scottish Rifles for a short time before commanding the fateful patrol.

Private Archibald Aberdeen was also wounded and taken prisoner. He succumbed to his wounds and died the next day, on 22nd December 1917. Private Aberdeen was buried by his German captors in a French cemetery behind their lines. In 1924, Private Aberdeen’s remains were reburied by the Imperial War Graves Commission in Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery among his comrades who died in the War.

Wilson and Thomson were awarded their Military Medals on 1st January 1918. Three days later, on 4th January, Lance Corporal John Barr Thomson died of his wounds and the hardships suffered during his ordeal in no man’s land. John Thomson was from Hamilton, Scotland, and was 38 years old at the time of his death. He is buried in Etaples Military Cemetery.

Sergeant John Wilson was also from Hamilton. He had joined the 6th Scottish Rifles, the local Territorial Force Battalion of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1912. John was a compositor with his local newspaper, The Hamilton Advertiser. Embodied for active service when war was declared in August 1914, John first went to France with the 6th Scottish Rifles in March 1915. Like Lieutenant Ewen, Sergeant Wilson was only transferred to the 10th Scottish Rifles a few months before he took part in the patrol. He had already been wounded in action, and had also served for a short time with an Officer Cadet School where he was considered for training as an officer. During the December patrol described above, Wilson had suffered a gun shot wound to the left thigh. In addition he suffered severe frost-bite as result of spending so long in wet, freezing conditions. The damage to his legs was severe enough to result in him having both legs amputated, and he was discharged from the army on medical grounds in April 1918, aged 24.

Sergeant John Wilson’s Military Medal is on display in Low Parks Museum, in his native Hamilton.

Comments:

Cameronians regimental collection named as of National Significance

The regimental collections of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) have been granted Recognition Status as part of a partnership bid through the Association of Scottish Military Museums. The award is made by Museums Galleries Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Government.

The combined Collection of the Scottish Regimental Museums has been Recognised as Nationally Significant to Scotland. These are the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, The Royal Regiment of Scotland, The Royal Scots, The Kings Own Scottish Borderers, The Royal Highland Fusiliers, The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), The Royal Highlanders (The Black Watch), The Highlanders (Queens Own Highlanders Collection), The Gordon Highlanders and The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

Together they tell part of Scotland’s story, since before the Act of Union up until the present day. This is only the second distributed collection application to be successful – the first being the National Burns Collection.

Regimental pattern officers sword, purchased by Sir Evelyn Wood VC for his son, Arthur

The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) collections are owned by South Lanarkshire Council, and are under the care and management of South Lanarkshire Leisure and Culture. The collection is showcased in Low Parks Museum in Hamilton. It charts the regiment’s history spanning almost 300 years of service across the globe. It contains objects from its Covenanting origins, to the disbandment of the 1st Battalion in 1968, and beyond. The core regimental displays were refurbished in 2013 through a project funded by Museums Galleries Scotland and The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) Regimental Trust. Low Parks Museum displays highlight the strong local connections The Cameronians shared with the towns and villages of South Lanarkshire. The regiment was originally formed as the Earl of Angus’ Regiment in Douglas, on 14th May 1689, and the 1st Battalion The Cameronians was disbanded there on 14th May 1968. Hamilton was home to the Regimental Depot from the creation of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1881 until its move to Winston Barracks in Lanark in 1947. Hamilton has also been home of the Regimental Collection since the 1960s.

Display of regimental uniform in Low Parks Museum

Star objects on show include the sword of William Cleland, first Commanding Officer of the Earl of Angus’ Regiment; one of the first Colours carried in battle by antecedent regiment – the 90th Perthshire Volunteers; a unique collection of regimental uniform; and a medal collection charting the Regiment’s involvement in conflicts since the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s to Aden in the 1960s – including seven Victoria Cross medals awarded to men of the regiment.

Model soldiers depicting a patrol in Aden, c.1966

Behind the scenes, continuing cataloguing and digitisation work helps improve our understanding of the objects in the collection, and their significance to local, Scottish and world history. A large selection of the regimental collections can be viewed online through South Lanarkshire Leisure and Culture’s website – http://www.slleisureandculture.co.uk/info/206/online

It is through the Association of Scottish Military Museums that the 10 museums work together. The Association also works closely with the Scottish National War Museum and the National Army Museum to ensure that Scotland’s military story is told to as wide an audience as possible. The Collection, comprising of over 160,000 objects, is distributed across Scotland; in Fort George, Aberdeen, Perth, Stirling Castle, Glasgow, Hamilton, and Edinburgh Castle, and also across the border in Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Miniature painting of the Honourable Mrs Graham, wife of Thomas Graham, founder of the 90th Perthshire Volunteers

The Recognition Scheme ensures that Scotland’s most important museum collections are identified, cared for and promoted to wider audiences. The award also opens up access for the partners of the Association of Scottish Military Museums to apply for Recognition funding from Museums Galleries Scotland to improve how people experience and engage with the Collection.

Comments:

Posted: 23/11/2017 by BarrieDuncan in Collections

Cameronian scoops top prize at Bisley

This fascinating photograph is contained within an old album in the regimental collection. It shows Private Brown of B Company, 1st Battalion The Cameronians – winner of the Imperial Prize competition at Bisley in 1894. The rather impressive silverware next to him are the challenge vases awarded as part of the prize; the other part being a personal cheque of £100 – a fair old sum for a Private soldier in 1894! Brown’s left hand rests on the stock of his Lee-Metford rifle with which he secured victory, and the honour of being forever immortalised in the records of his Regiment.

Private Brown, winner of the Imperial Prize at Bisley, 1894

The entry in the regimental Digest of Service for 1894 records that:

“The Battalion gained a large number of Prizes at the Browndown Rifle Meeting. At Bisley, the Imperial Prize which was open to Officers, N.C. Officers & men of the Regular Army was won by Pte J. Brown of the Battalion, who secured himself £100 & a pair of very handsome Silver Challenge Vases which were placed in the Officers Mess.”

1894 was the first year the Imperial Prize was competed for at Bisley, the home of British competition shooting since 1890. The Imperial Prize was competed for over two days of shooting. On the first day, competitors were allowed seven shots at targets placed at 200, 500, and 600 yards distance. Once the points were tallied, the top 100 progressed to the second and final day of shooting, comprising of 15 shots at a distance of 800 yards.

Newspaper reports from the time record that the weather over the two days of shooting was far from ideal, with heavy rain and high winds. At the end of the 500 yards stage of the event, the two highest scorers were a Lieutenant of the Scots Guards, and a Sergeant of the Northamptonshire Regiment. A good round at the 600 yards target saw Private Brown of The Cameronians in contention for the win, in what turned out to be a very close final round:

“The contest virtually lay between Col.-Sergt Phillips, Sergt.-Major Brown, and the winner. The sergeant-major finished with 152, at which time Private Brown had 148, and two shots to go. His fourteenth was a bull. He took a long aim for his last, and as the signal from the target was some time in making its appearance it was thought he had missed. A cheer was raised when a bull was signalled.”

Edinburgh Evening News, 13th July 1894

Private Brown won the competition with a score of 158, five points clear of the runner up, Captain Cowie of the Royal Engineers. Described in one newspaper account as a ‘young’ soldier, Brown was almost 40 years old when he won the Imperial Prize, and had originally joined the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry, an antecedent regiment of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), in February 1874. The article from the Edinburgh Evening News closes with the remark “Up to this year the winner had not been an abstainer from ardent spirits, but he is, and has been all this year, a teetotaller.” This somewhat curious statement takes on new meaning when one examines Private Brown’s service record. Born in Londonderry, John Brown enlisted for service at Hamilton on 28th February 1874, aged 18 and 6 months. He had previously been occupied as a Labourer. Brown’s military service got off to something of a rocky start when, after only five months service, it was discovered that he had neglected to mention he was actually enrolled in the Londonderry Light Infantry militia at the time of his enlistment with the 90th. There follow a number of instances of imprisonment by order of the Commanding Officer, until September 1876 when Brown is transferred to the 73rd Regiment (another Perthshire regiment). Whether this transfer was at his own request, or by order of the Commanding Officer of the 90th, is not recorded. The transfer did, however, mean that Private Brown would miss active service with the 90th in South Africa (1878-1879).

While with the 73rd, Brown continues to appear before his Commanding Officer resulting in further spells in prison, and numerous instances of loss of Good Conduct Pay. Despite his frequent clashes with regimental authority, Brown is permitted to extend his period of service to 12 years ‘with the Colours’ in July 1879. This would suggest that, while numerous, the nature of these ‘crimes’ were not serious enough to warrant discharge and were probably related to drunkenness.

Brown re-joined the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry on 30th September 1880, remaining with it through it’s transition to become the 2nd Battalion Scottish Rifles following the amalgamation with the 26th Cameronian Regiment in 1881. The cycle of ‘Awaiting Trial’ followed by ‘Imprisoned’ along with the occasional ‘Forfeiture of Good Conduct Badge’ continue until early 1894. A spell of good behaviour sees his first Good Conduct Badge restored on 28th February 1894, followed by a second on 30th August of that year. If the newspaper article quoted earlier is to be believed, we might assume that this period of improved conduct is a result of Private Brown’s newly found sobriety. Whether this change in personal circumstance also led to Brown’s success at Bisley can only be guessed, but we can assume that he had already demonstrated some skill at musketry before winning the Imperial Prize. This photograph is from another album in the regimental collection and is captioned simply as “Shooting Trophies – Aldershot – 1891-1893”:

Private Brown is standing in the back row, fifth from the right. His appearance in this photograph might suggest he was already an accomplished marksman and may have indeed contributed to the securing of one or more of the prizes on display.

As the above photograph demonstrates, The Cameronians were not unused to success in competitions of shooting and musketry. In 1893, the 1st Battalion had taken 1st and 2nd Prize in the “Evelyn Wood Competition” at Bisley; a group event focused on a mix of marching and shooting. Still, winning a competition as grand as the Imperial Prize was something worth celebrating:

“Private Brown, of the Cameronians, who won the Imperial Cup at Bisley, returned to Portsmouth, where his regiment is quartered, on Saturday night, and met with a right royal reception… A telegram was received by the regiment during the evening from Sergeant-Major Brightman that the winner would arrive by the 9.43 train. Accordingly a waggonette, with the regimental band and pipers, was at the station to receive him. The news had got abroad, so that besides his comrades there was a large crowd ready to meet the successful marksman. The train was about an hour late and when it did draw up at the low level platform there was an enormous crowd awaiting it. On emerging from his compartment, Brown experienced an enthusiastic reception, and the crowd and his comrades carried him amid ringing cheers to the waggonette, while the band struck up “See the Conquering Hero Comes.” The cups were carried by Sergeant-Major Brightman and Sergeant-Instructor Jennings. On reaching the barracks Brown was escorted to the Officers’ Mess, where he was received by the officers, who complimented him heartily on his success.”

Hampshire Telegraph, 28th July 1894

Further evidence of the Battalion’s pride in securing the Imperial Prize is demonstrated by the above photograph being published as a postcard by the Battalion in 1894, with the addition of some recently acquired silverware!

Postcard published by The Cameronians in 1894. The challenge vases won as part of the Imperial Prize have been super-imposed in front of the display of silverware won by the Battalion.

Following the restoration of his Good Conduct Badges in 1894, there are no further reprimands or reductions logged in Private Brown’s service records and he was finally discharged from the 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) on 30th March 1895, with 21 years and 34 days service under his belt. Of this, 19 years and 251 days would count towards his pension – bad behaviour comes with a cost after all!

Comments:

Log in