Airborne Cameronians

Continuing with the theme of service in wartime ‘special forces’, this post will look at some of the Cameronians who served with the Parachute Regiment in the Second World War.

Prior to the Second World War, Britain had no established airborne forces. Use of parachute troops by the German army in the early stages of the War led to No. 2 Commando being turned over to parachute training in June 1940, for possible future operations in an airborne role.

As a completely new venture so far as British forces were concerned, there was much to be learned and this often by trial and error. The risks associated with such an undertaking were many, and could ultimately prove deadly:

“By September [1940] some 340-odd other ranks of No. 2 Commando had parachuted, but the wastage rate had been discouraging inasmuch as there had been two fatal accidents, twenty badly injured or declared medically unfit to carry on, whilst thirty of the original volunteers had refused to jump and had been RTU’d [returned to unit].”[i]

In February 1941 the paratroopers of No. 2 Commando had their first taste of action during Operation Colossus; an airborne demolition raid of an aqueduct in southern Italy. The unit was renamed as 1st Parachute Battalion in September 1941, additional battalions being raised from volunteers across the Army to form the Parachute Regiment.

John Frost

John Dutton Frost, or Johnny as he was affectionately known, is perhaps one of the most famous airborne commanders of the Second World War. His actions as commander of British airborne forces at Arnhem during Operation Market Garden were immortalised on screen in the blockbuster movie A Bridge Too Far in which he is portrayed by Anthony Hopkins.

Second Lieutenant Frost joined 2nd Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in September 1932, while the Battalion were stationed at Glasgow’s Maryhill Barracks.[ii] Frost would serve with the 2nd Battalion in Palestine in 1936, before being seconded to the Iraq Levies in 1938. Frost was still serving in Iraq when the Second World War broke out; it wasn’t until January 1941 that he was able to re-join The Cameronians, being attached to the Infantry Training Centre (ITC) at Hamilton and given command of the Specialist Company.[iii] Captain Frost remained at the ITC until March 1941, when he was posted to the Regiment’s 10th Battalion, then employed on Home Defence duties on the Suffolk coast under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel D. G. Moncrieff-Wright MC.

Frost put his name forward for parachute training when the call went out for volunteers to create the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Parachute Battalion. It was not without serious misgivings that Frost volunteered, being torn over his loyalty to the Regiment, the Battalion and to Colonel Moncrieff-Wright, whom he greatly respected.[iv]

Initially posted as adjutant of the newly formed 2nd Parachute Battalion, Major Frost would go on to command the Battalion’s first combat action – Operation Biting, also known as the Bruneval Raid. The target for Operation Biting was the German radar installation near the coastal village of Bruneval, France. In order that Britain could hope to counter-act the effects of this new technology, a sample of the equipment was required for study and analysis. ‘C’ Company of 2nd Parachute Battalion would conduct the raid; dealing with the German defenders and removing the necessary components from the radar station before being evacuated from the nearby beach by the Royal Navy. The operations success was a huge morale boost for Britain, and helped cement the Parachute Regiment’s reputation as an elite fighting force. The raid also put Frost firmly in the lime-light – reporting to Churchill and his Chiefs of Staff in person for an immediate debriefing on his return from France. Frost was awarded the Military Cross for his command of the operation; he collected his award from Buckingham Palace in the uniform of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

Frost would ultimately go on to command 2nd Parachute Battalion, and lead the unit in its most famous action – possibly one of the most famous actions of the War – Operation Market Garden.

The 2nd Parachute Battalion were the only unit of allied airborne forces to reach the ultimate objective of the operation – the bridge over the Rhine at Arnhem. The paratroopers had expected to hold the bridge against relatively light German resistance for two days while allied reinforcements were brought up by road. Various delays and setbacks however saw Lieutenant-Colonel Frost and his men hold the bridge for nearly four days against repeated counter-attacks by the German 9th Panzer Division. In the face of mounting casualties against overwhelming odds and with no prospect of reinforcement or resupply the survivors of 2nd Parachute Battalion were forced to surrender. Frost, by then twice wounded, and the remnants of his unit would spend the rest of the war as Prisoners of War.[v]

Frost remained in the British Army after the war, ultimately reaching the rank of Major-General. Before his retirement from the Army in 1968, Major-General Frost had been General Officer Commanding 52nd (Lowland) Division District, and as such enjoyed close contact with his old regiment. Major-General Frost was a frequent attendee of regimental dinners and commemoration services. He was also a regular contributor to The Covenanter and wrote several fascinating articles about service life.

In addition to his many military honours (he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath, awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Bar, and the Military Cross) Frost also had the distinction of having the bridge over the Rhine at Arnhem renamed in his honour as John Frostbrug, or John Frost Bridge, in 1978.

Frost was just one of many senior, ex-regimental officers to attend the disbandment ceremony of the 1st Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) at Douglas on 14 May 1968. He would go on to record his thoughts on the disbandment in his autobiography:

“When one joins a regiment, one thinks that it is forever. It seems to be such a highly durable thing – the territorial background, the customs and traditions, the property, the uniforms, the music and the families, and, last but not least, the battle honours and the memorials, including the colours which may be laid up. It comes as a very savage shock to learn that a regiment will be no more.”[vi]

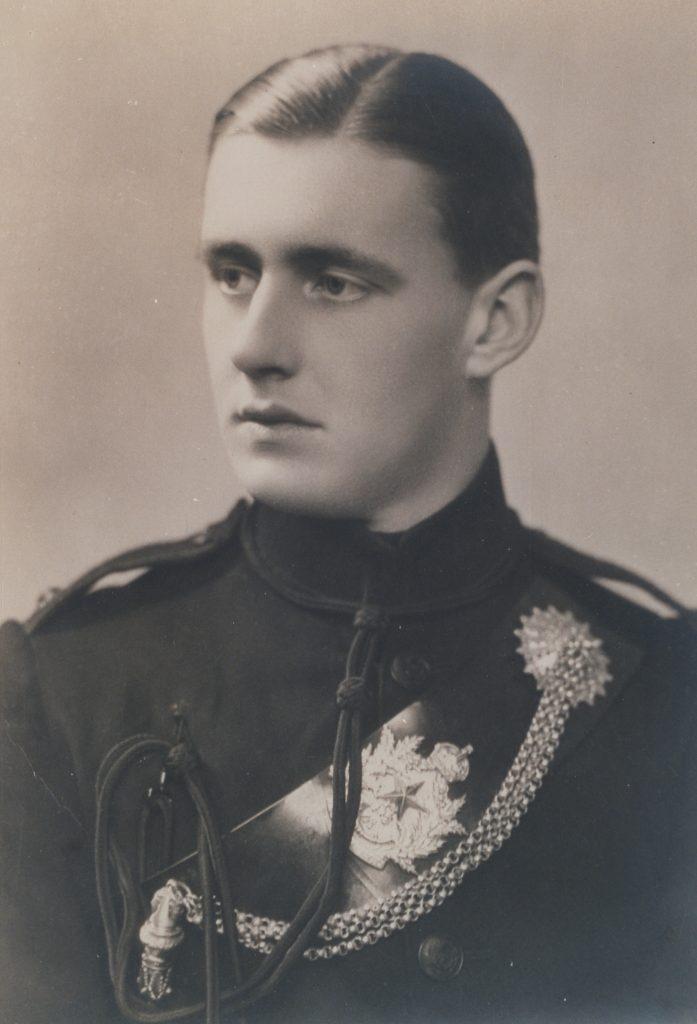

Hugh McIntyre

Major John Frost was not the only Cameronian to air-drop into France in February 1942 as part of Operation Biting. Hugh Duncan McDonald McIntyre was a young soldier from the 9th Battalion The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) who had also volunteered for parachute training and ultimately found himself in the 2nd Parachute Battalion. Hugh was one of a number of parachute volunteers from Scottish regiments; these men being formed into a ‘Jock’ Company of 2nd Parachute Battalion.

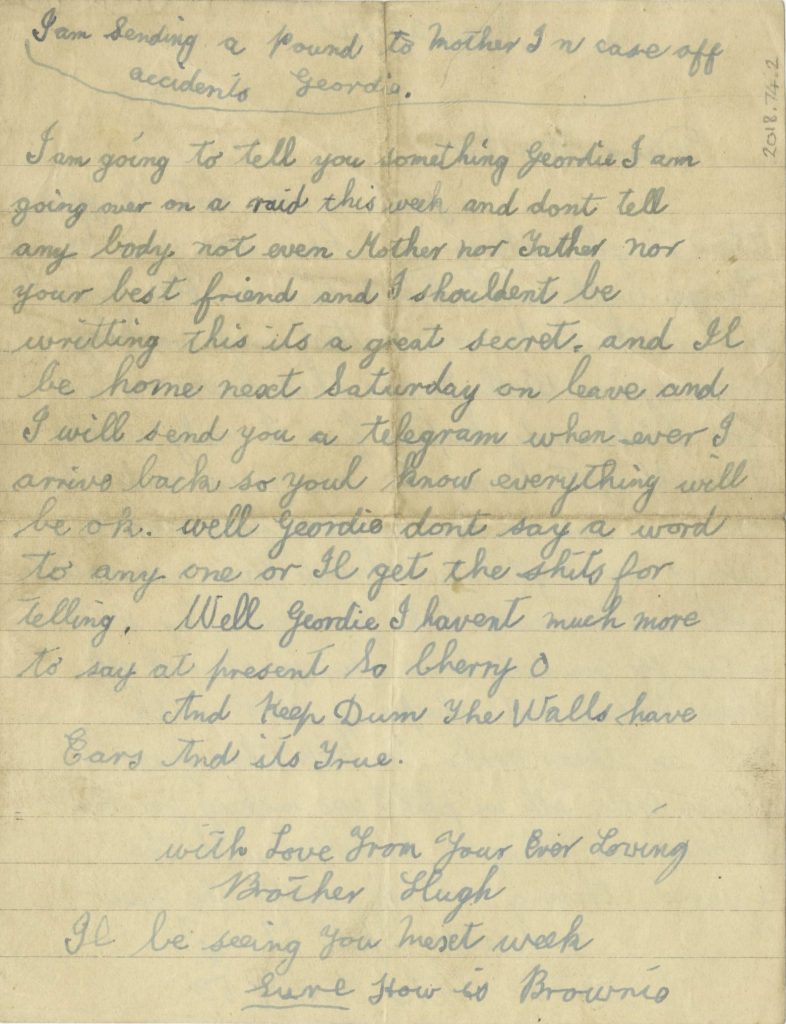

Hugh wrote to his brother, Geordie, on 21 February 1942, in which he let slip that he would soon be going on a raid and begging him to secrecy:

“I am going to tell you something Geordie, I am going on a raid this week and don’t tell anybody, not even mother or father nor your best friend and I shouldn’t be writing this, it’s a great secret. And I’ll be home next Saturday on leave and I will send you a telegram whenever I arrive back so you’ll know everything will be OK. Well Geordie, don’t say a word to anyone or I’ll get the shits for telling. Well Geordie I haven’t much more to say at present so Cheery O. And keep dumb, the walls have ears and it’s true.

With love from your ever loving brother, Hugh.

I’ll be seeing you next week…”

The McIntyre family would never receive the telegram from Hugh, telling them ‘everything is OK.’ Instead they would receive the news the families of every service-person must fear most; that their loved one had been killed in action. Hugh was one of two men from 2nd Parachute Battalion killed during Operation Biting. The ‘hit and run’ style nature of the operation meant that the bodies of the two men killed had to be left behind.

News of the raids success was quickly released to the press and splashed across newspapers the length and breadth of the UK and beyond. As Frost would later explain:

“The Bruneval raid [Operation Biting] came at a time when our country’s fortunes were at a low ebb. Singapore had recently fallen and the German battleships had escaped up the Channel from Brest in the very teeth of everything that could be brought against them. Many people were disgruntled after a long catalogue of failures, and the success of our venture, although it was a mere flea-bite, did have the effect of making people feel that we could succeed after all.”[vii]

Hugh Duncan McDonald McInytre is buried in St. Marie Cemetery, Le Havre, France. Buried alongside him is Allan Scott of the Berkshire Regiment; 2nd Parachute Battalion’s other casualty from Operation Biting.

The 12th Battalion’s Parachuting Platoon

12th Cameronians was perhaps one of the finest wartime Battalions never to see combat service as a unit. Raised shortly after the outbreak of War, 12th Cameronians spent many months in a Home Defence role in the north of Scotland, before a fifteen-month spell as a garrison unit on the Faroe Islands. Well trained and well led, it was unfortunate that the 12th Battalion, on its return to the UK in late 1943, was to be disbanded and its officers and men transferred to units already on field service or preparing for the invasion of Normandy. Large numbers of men from 12th Cameronians would soon see service in North Africa and Italy with the Royal Fusiliers and the Essex Regiment.

Five officers and 40 men from 12th Cameronians volunteered for parachute training and were formed into a ‘Jock’ platoon of the 7th (Light Infantry) Parachute Battalion. As part of 6th Airborne Division, 7th Parachute Battalion would land in Normandy on the morning of 6th June 1944; their objective to help secure and defend the bridge over the Caen canal near Bénouville – later known as Pegasus Bridge. Major E. H. Steel-Baume, a regular officer of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) and early parachute volunteer, was Second-in-Command of 7th Parachute Battalion during the D-Day drop. Several men from 12th Cameronians were killed or wounded during airborne operations in Normandy, including C.Q.M.S Stanley Savill, a pre-war regular who had served with 1st Cameronians in India, and Lance Corporals George Hand and Robert Twist.

7th Parachute Battalion would see further action in the Ardennes, and in the crossing of the Rhine in the final stages of the War.

Writing in January 1945, Major Ramsay Tullis, one of 12th Cameronians’ officers who went to 7th Parachute Battalion records:

“It is sad to record that two officers, Captain Fotheringham[viii] and Lieutenant Nelson[ix] and eleven O.R.’s [Other Ranks] remain with the battalion out of the original platoon, but, on the other hand, it is most gratifying that this small band of Cameronians should have acquitted themselves in a way of which the regiment may be proud.”[x]

[i] Dunning, James It Had to be Tough: The origins and training of the Commandos in World War II, Frontline Books, London, 2012, p179

[ii] Frost, John Dutton Nearly There: The Memoirs of John Frost of Arnhem Bridge, Leo Cooper, London, 1991, p16

[iii] Those Were the Days! By Koi-Hai (Major R. G. Hogg) published in ‘The Covenanter’, Winter Number 1971, p82

[iv] Major-General Frost would write a heart-felt tribute to his old Commanding Officer in The Covenanter, when the latter’s death was announced in the 1983 issue, in which he said “Though he [Moncrieff-Wright] would never claim to have a place among the very distinguished officers the regiment has produced, I would place him there.” The feeling was mutual; Colonel Moncrieff-Wright had written in his own copy of A Drop Too Many “He [Frost] was in my Battalion and I liked him – he was an excellent officer and I knew he would do well.”

[v] For Frost’s full account of the Operation, and indeed his wartime military service, see A Drop Too Many, Cassell, London, 1980

[vi] Frost, Nearly There, p183

[vii] Frost, A Drop Too Many, p58

[viii] Later wounded in the Rhine crossing

[ix] Died of wounds received in the Rhine crossing

[x] Cameronians in the 6th Airborne Division, by Major Ramsay Tullis, published in ‘The Covenanter’, January 1945, p92

Comments: 0

Leave a Reply